“It must not be forgotten that although a high standard of morality gives but a slight or no advantage to each individual man and his children over the other men of the same tribe, yet that an increase in the number of well-endowed men and an advancement in the standard of morality will certainly give an immense advantage to one tribe over another… and this would be natural selection.

At all times throughout the world tribes have supplanted other tribes; and as morality is one important element in their success, the standard of morality and the number of well-endowed men will thus everywhere tend to rise and increase.”

~Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man

The Tree of Knowledge...

To accept as a theme for discussion a category that one believes to be false always entails the risk, simply by the attention that is paid to it, of entertaining some illusion about its reality.

~Claude Lévi-Strauss

Systematic error

Welcome to this introductory course on philosophical ethics. Although I'm very excited about teaching this material, I'd like to begin with an admission: this is a very difficult class to teach. This is because philosophical ethics has, despite its two millennia history, failed to produce a dominant theory. To be honest, this is to put the point charitably. Nick Bostrom makes the point a little more forcefully. Since there is no ethical theory (or meta-ethical position) that holds a majority position (Bourget and Chalmers 2013), that means that most philosophers subscribe to an ethical theory that is false (Bostrom 2017: 257). Put differently, imagine that a theory that we will eventually cover, say, utilitarianism, turns out to be true. Per the survey by Bourget and Chalmers, only about a third of ethicists subscribe to this view. That means that, at least in our little hypothetical scenario, two-thirds of ethicists are wrong (since they don't subscribe to utilitarianism). The same could be said of any ethical theory, since about a third is the most any ethical theory gets. In other words, the field of philosophical ethics is characterized by systematic error. How is one expected to teach an introductory course to a field where most theorists are wrong?

What I've decided to do in this course is to frame the entire course within the context of systematic error. My assumption is that, if systematic error is the state that the field is in, then a proper introduction to the field should leave you in utter moral disarray. What I'd like to do in this first lesson is give you a theory as to why the field of ethics is in a state of utter chaos—a theory I'll give in the next section. I'd also like to make three important points today in the hopes that, at the conclusion of the course, you might be able to understand how these points are manifested in the way that I've taught this class. Here are the three points:

- The field of philosophical ethics is characterized by systematic error.

- The field of philosophical ethics has many famous theorists who themselves proposed morally abhorrent positions.

- The field of philosophical ethics cannot credibly make the case that ethical reflection has improved the world.

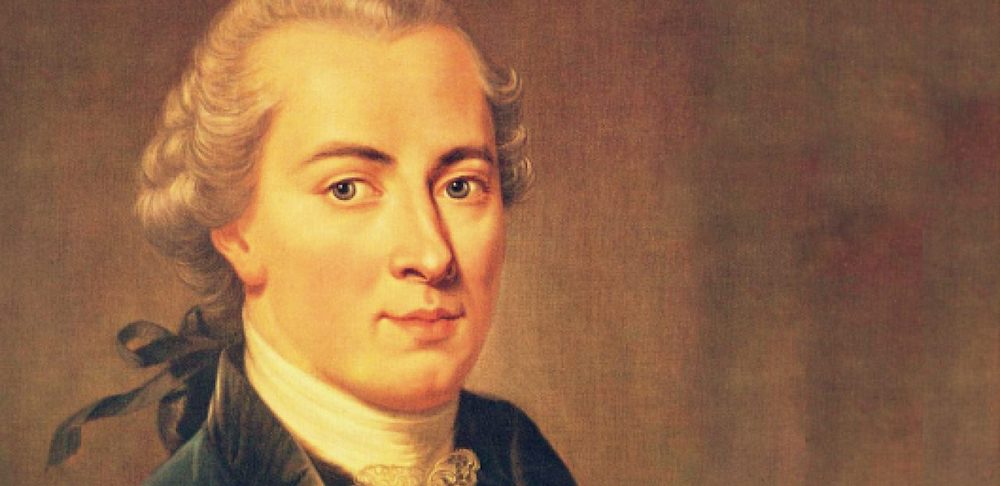

Let's cover the first point in this section. First off, there is no dominant view in ethics. As mentioned before, per the survey Bourget and Chalmers, about a third of ethicists are consequentialists (some sort of utilitarianism). Another third lean towards deontology, which we will cover in its Kantian form—coming from the mind of Immanuel Kant. Lastly, the virtue tradition (which was popularized by Aristotle) comes at a distant third, with less than a fifth of ethicists subscribing to the view. Other views are influential in other subfields. For example, newer versions of social contract theory seem to dominate in political philosophy (Mills 2017). But at least in the subfield of ethics, there is no majority view. You have, at best, a tie for a plurality. That looks like a whole field of inquiry that has failed to achieve consensus

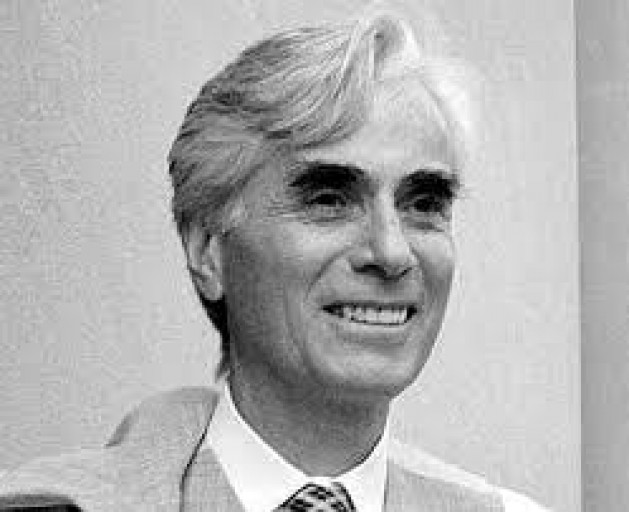

Francis Crick (1916-2004).

Second, the failure of philosophers to arrive at a dominant view in ethics is glaringly obvious to other disciplines. In her recent book Conscience, Patricia Churchland gives an anecdote about how she and the famous molecular biologist Francis Crick attended an ethics lecture, and Crick was dismayed that the focus was on pure reason, attempting to arrive at moral truth through reason alone. Clearly, Crick argued, our genetics play a role in our sociality, including our moral behavior; and philosophers need to discuss that. Churchland reports that Crick essentially made an argument in the style of a theorist that we will eventually cover: David Hume. Crick's point was very Humean indeed—reason cannot motivate action; morality is about action; thus, reason cannot drive moral behavior.

Crick's disbelief brings me to the third point. Even worse than the recognition by biologists, among others, that ethicists have failed at their job is the fact that ethicists are fighting back when others try to do what they couldn't do. Although there has been a push for more empirical approaches in ethics, i.e., more incorporating of findings from the sciences into our ethical theories, there has been strong and consistent push-back from non-empirical philosophers. In fact, some philosophers would be horrified to see that I teach this course the way that I do—devoting all of Unit III to an empirical assessment of some popular ethical theories. But my reasoning is simple. I wanted to show ethics as it really is: with all ethical theories running into problems.1

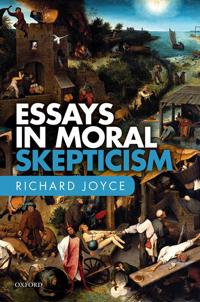

Lastly, even empirical approaches to understanding our moral behavior have not panned out. One camp of theorists that uses the natural sciences to fuel their arguments—a group we will refer to as moral skeptics—agree that moral objectivism is wrong, i.e., that there is no such thing as objective moral values, but they don't know where to go from there (see Garner and Joyce 2019). Their general options appear to be: conservationism (keeping moral language and moral reasoning intact), moral fictionalism (pretending morality is real but acknowledging that it is a fiction), and abolitionism (discontinuing the use of moral reasoning and moral language). The most prominent skeptic, Richard Joyce, chooses moral fictionalism, but his own intellectual descendants disagree with him. This is pervasive disagreement—a likely indicator of systematic error.2

Food for Thought...

Moral disarray

Before moving on to the second and third points that I want to make about philosophical ethics, it might be good for us to consider why it is so difficult to define the word good, at least in its moral sense. To this end, I will enlist the aid of Alisdair MacIntyre, whose After Virtue and A Short History of Ethics were instrumental in building this course. Here's his point in a nutshell. MacIntyre argues that moral discourse is in disarray and that the only discipline (history) that is poised to discover this fact, as well as its cause, was not codified as an academic discipline until after (or during) the period in which normative language was disrupted inexorably. Clearly, there's a lot to unpack here.

What MacIntyre is getting at is that we have lost track of the very meaning of moral and then we forgot we lost track of it. Per his research, MacIntyre has discovered that there has been distinct moral discourses (with their own moral logics) throughout history. In the ancient period of the Western tradition—think Ancient Greece—moral terms were only used in a means-end context. This means that you only used moral terms in an "if you want this, then you should do that" sense. For example, in one theory we'll be covering, what is moral is simply what God commanded. So, the moral logic is this: if you don't want to go to hell, then follow these commandments (and that's what good is). In another theory we'll be covering, the whole point of morality is to build ourselves so that we'll respond to the right situations with the right actions; this is called the virtue tradition. The moral logic is this: if you want to flourish at your social role (whatever that may be), then develop those virtues that will lead to success in this role (and that's what good is).

What happened after this, according to MacIntyre, is the increased contact between radically different social orders. To continue with our Greek example, due to conquest and trade, the Greeks came into contact with many different peoples and cultures. Once they learned of their norms and customs, they began to debate what actions were simply done due to custom and which actions truly where right for everyone. And this is when moral debate began to get messy.

The state of philosophical

ethics today.

But it didn't stop there. There was only more contact between different peoples as new empires rose and fell. Eventually, thanks in part to the printing press (and fastforwarding substantially), there was a facility to the exchange of ideas, including ideas about morality. And so in the 18th century, Enlightenment thinkers began to continue this debate about what moral terms mean, and they pushed it to its logical extreme. This pushing of the envelope culminated in the work of Immanuel Kant, who defined moral terms in the most absolutist sense possible: morality is independent of desires, of context, and of consequences. What is moral, according to Kant, is what is commanded by reason; for no other reason other than it must be.

By this point, there were many moral discourses and many moral logics. And the debate continued. Sometimes we use the word good in the sense that what is moral is simply what God commanded. Sometimes we use it more like in the sense that a virtue ethicist would use it. Sometimes we use it the way Kant uses it. And sometimes we use it in culturally-dependent way. And this is why MacIntyre characterizes modern philosophical ethics as interminable. The debates are, or appear to be, endless. Moreover, there seems to be no method by which to resolve disagreements. Why? Because we all use moral terms in different senses at different times, moral terms lost their previously-fixed meaning, and we've completely forgotten this whole history. Utter linguistic anarchy.3

Per MacIntyre, the only real moral logic that makes sense is that of the virtue tradition. This is because to use the term good correctly, one must have some role in mind. It doesn't make sense to simply say, "So and so is good." The rest of us would rightfully ask, "Good at what?" So there is no good in general, there's only good manager, good athlete, good teacher, etc. Contextualized by a social role is the only sense in which moral terms mean anything at all.4

What's been swept under the rug...

Let's consider now the second point I want to make: the field of philosophical ethics has many famous theorists who themselves proposed morally abhorrent positions. I will only discuss one ethicist's morally abhorrent positions, but you'll likely agree with me that it's enough. The thinker I have in question is none other than Immanuel Kant, champion of deontological ethics, as you will soon learn. Ethicists usually sidestep the various empirical claims that Kant made which are empirically false, arguing that his ethical theory is independent of these claims (see Mills 2017: 97-102). This is very convenient since these empirical claims are not only false, but one can easily make the case that they're dangerous too. In fact, Kant was a pioneering theorist of “scientific” racism. Eze (1997) cites various “findings” in Kant’s “anthropology.” Be warned: these quotes are disturbing.5

I obviously don't sweep these under the rug. We gain nothing from not exposing white supremacy when we see it. I'll go further. Philosophy as a field is guilty of down-playing the racism of many of its most famous theorists. Political philosopher Charles W. Mills gives us a quick overview below, and I've taken the liberty to bold those theorists that we will cover.

“John Locke invests in African slavery and justifies aboriginal expropriation; Immanuel Kant turns out to be one of the pioneering theorists of ‘scientific’ racism; Georg Hegel’s World Spirit animates the (very material and non-spiritual) colonial enterprise; John Stuart Mill, employee of the British East India Company, denies the capacity of barbarian races in their 'nonage' to rule themselves” (Mills 2017: 6; emphasis added).

The field itself still might harbor silent animosity towards non-whites. Jorge Gracia (2004) discusses how the stereotype of the philosopher excludes the mannerisms of various Latin American cultures. This effectively means that if a Latin American person wants to be a philosopher, they have to drop their cultural mannerisms, including such personal characteristics as humor (since philosophers are supposed to be serious), speed of conversation (since philosophers are supposed to be slow and methodical in their speech), and even their accent.

“To have a British accent is an enormous asset, particularly in philosophy. Some American philosophers actually adopt one after they visit Britain… But the situation is different with other accents, a fact Italian, Irish, and Polish immigrants know only too well. For Hispanics, matters are even worse because our accent is not perceived as being European—it is associated with natives from Latin America, Indians, primitive people! For this reason, there is a strong predisposition among American philosophers not to take seriously anything said by Hispanics with an accent” (Gracia 2004: 305).

No proof of effectiveness

Let's close with the third point I want to make in today's lesson: philosophical ethics cannot credibly make the case that ethical reflection has improved the world. Sure. There are some thinkers, like Steven Pinker, that argue that the decrease in interpersonal violence and warfare over the last few centuries is a by-product of Enlightenment values. In his Better Angels of Our Nature, he argues that part of the reason for the dawn of Enlightenment values was a coherent moral philosophy. Take a look at the passage below (again with the thinkers we will be covering in bold).

“I am prepared to take this line of explanation a step further. The reason so many violent institutions succumbed within so short a span of time was that the arguments that slew them belonged to a coherent philosophy that emerged during the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment. The ideas of thinkers like Hobbes, Spinoza, Descartes, Locke, David Hume, Mary Astell, Kant, Beccaria, Smith, Mary Wollstonecraft, Madison, Jefferson, Hamilton, and John Stuart Mill coalesced into a worldview that we can call Enlightenment Humanism. It is also sometimes called Classical Liberalism” (Pinker 2012: 180; emphasis added).

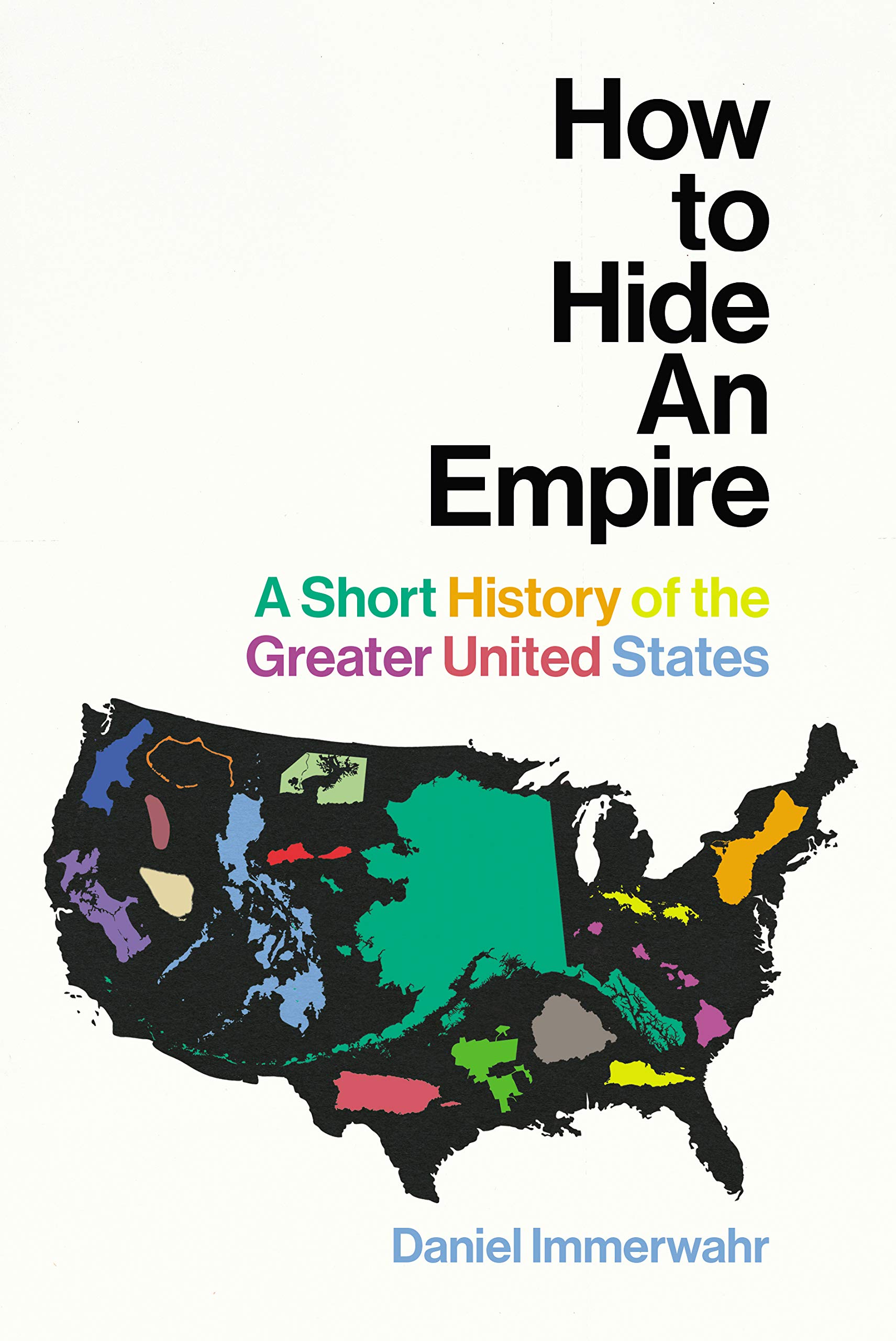

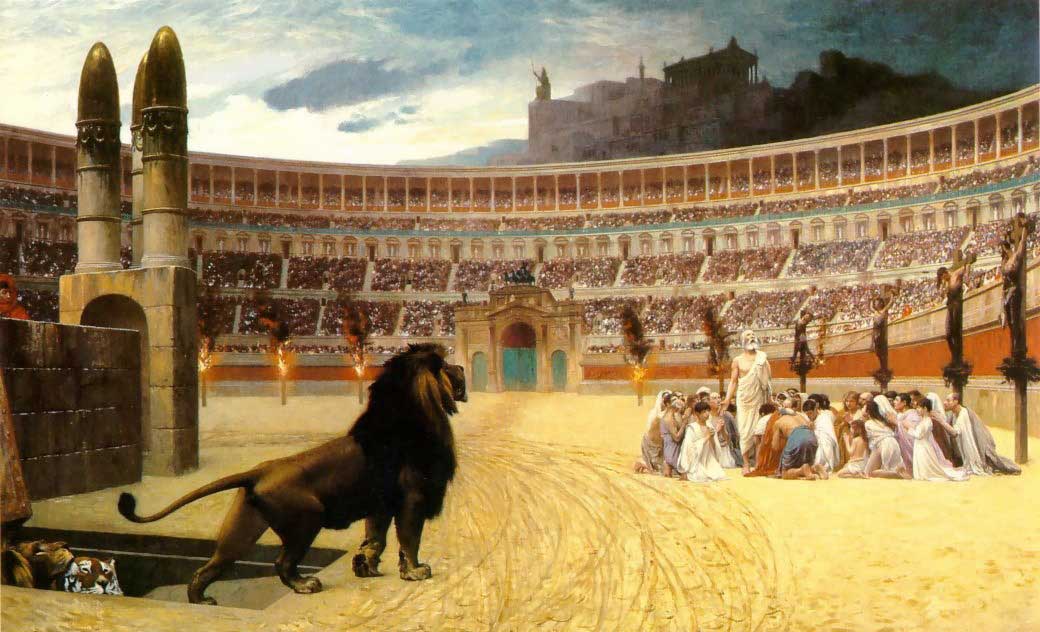

Although Pinker might be partially right, there are other viable explanations for this decrease in violence. Just like we will see Kyle Harper explain the rise of Christianity without assuming its truth (see the Death in the Clouds series), we can similarly explain our improved moral behavior and outlook without assuming that moral judgments actually have this world-changing force. One example of this might be found in how the age of colonialism came to an end.

Today colonialism is looked at as morally abhorrent. We lament the genocide of the Native Americans, the eradication of thousands of native cultures and languages, and the practice of occupying a territory only to drain it of its natural resources as was done in Latin America (by Spain, Portugal, and France), in Africa (by Britain, France, Germany, Portugal, Belgium, and Italy), and in Asia (by Britain, France, Portugal, Spain, the Netherlands, and the US). We are righteously upset over the overthrow of governments (sometimes democratically-elected ones) by both the US and the USSR during their Cold War. We now acknowledge that this was all bad (even if it is ongoing in some parts of the world). The question is: why did imperialists change their minds? Was it a moral awakening? Or something else?

Immerwahr gives an explanation of why the US gave up many of its colonies in the middle of the 20th century in the slideshow below. And it has nothing to do with being morally enlightened...

In fact, my friends, there is literally no evidence that studying ethics makes you a more ethical person (see Schwitzgebel 2011).

But then again...

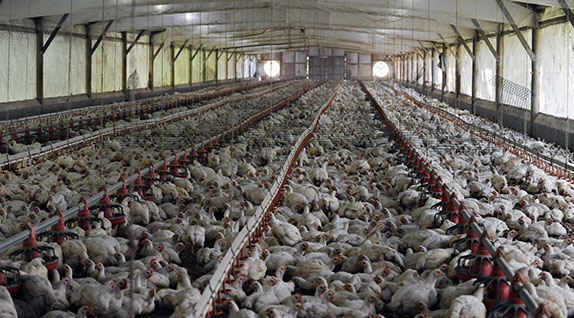

It might seem like this class is all for nothing, but let me say one thing that might change your mind. We’ll be looking primarily at explanations and theories as to why some things are morally right or morally wrong. At this level, there is much disagreement. But at the surface level, the waters today are much calmer. Ethicists actually do agree on several things. Devoting your time and effort to helping others and to social movements is almost universally encouraged. Ethicists agree that we should all be more charitable. Although not everyone agrees that being vegan is morally necessary, most ethicists acknowledge that our current animal agriculture needs to be reformed. Ethicists agree that gender and racial equality must be strived for. And ethicists nearly unanimously claim that we need to take better care of our planet, both as individuals and as a collective, for ourselves, our friends, and our descendants.

And so perhaps studying ethics can at least help us imagine a better tomorrow. Who knows? Maybe one day our grandchildren, or our great great great grandchildren, will live in a world free from gender and racial injustice, free from animal cruelty, free from human self-destructiveness. Maybe they'll have to go to museums to see what life was like when the world was full of unnecessary suffering. Their history classes will teach them about how sapiens used to spend so much time and effort in fighting and war, and they'll find it strange that poverty existed at all. Racism, sexism, and homophobia won't even make sense to them. And the history courses that they will take surveying all of the injustices of the past can end with the following words... "And then there were none."

To be continued...

Footnotes

1. Two points that I should add here. It's also the case that I teach the course the way that I do because I am a so-called analytic philosopher. In fact, I am not only in the analytic branch of Philosophy (which seeks to make its theories continuous with the natural sciences), but I am considered a radical even within this branch. My position is officially referred to either as philosophical naturalism or neopositivism, but I've also been referred to as an empirical philosopher, if the person is being kind, and as a ruthless reductionist or a logical positivist (which is supposed to be an insult since that view was refuted) when they don't like my views very much. Second, there is actually an increasing number of empirical philosophers, but they tend to publish in various disciplines besides Philosophy, such as in the Cognitive Sciences, e.g., Daniel Dennett. I wanted to make sure we included them in this introductory class and so that is another reason why Unit III is the way it is.

2. On a personal note, one of my primary philosophical interests is in the area of the philosophy of artificial intelligence. An important philosopher who works in this field is Nick Bostrom (mentioned above). Bostrom argues that the possibility of general domain artificial superintelligence poses an existential risk to humankind; the interested student can see the lesson titled Turing's Test from my 101 course. Among the many problems he challenges us to consider, an important one for me is the motivation selection problem: the question of how to make "friendly" AI—AI with a friendly disposition that wouldn't be inclined to harming humans. Perhaps another way of posing this problem is to wonder how to make AI that follows moral rules such as, "Don't destroy all of humanity". As previously mentioned, Bostrom argues that since there is no ethical theory (or meta-ethical position) that holds a majority position, then that means that most philosophers subscribe to an ethical theory that is false. As such, they are no help when attempting to build “friendly” AI. They can't help us decide whether artificial minds deserve moral rights. They can't even tell us whether morality can even be programmed for.

3. In chapter 2 of After Virtue, MacIntyre also makes the interesting point that if his hypothesis is true, it will seem completely false. This is because the very function of the moral and evaluative terms we use is corrupted and in disarray, and so we do not have the language by which to point out the corruption and disarray. Anarchy indeed.

4. MacIntyre makes several arguments against other moral discourses and other moral logics. The problem with each theory is unique to itself. For example, the problem with a view called divine command theory is that it relies on the existence of God—something which MacIntyre wouldn't bet on. The problem with, say, utilitarianism, is that it relies on naturalism about ethics, the view that moral properties (like moral goodness) are actually natural properties (like pleasure). The interested student should refer to MacIntyre's After Virtue for a full analysis, although you should be warned that it is a very challenging text.

5. Kant also made accurate empirical predictions. We will cover those in time.

...Of Good

and Evil

It has often and confidently been asserted, that man's origin can never be known: but ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge: it is those who know little, and not those who know much, who so positively assert that this or that problem will never be solved by science.

~Charles Darwin

Back to the beginning...

Let's turn the clock back—way back... A genus is a biological classification of living and fossil organisms. This classification lies above species but below families. Thus, a genus is composed of various species, while a family is composed of various genera (the plural of genus). The genus Homo, of which our species is a member, has been around for about 2 million years. During that time there has been various species of Homo (e.g., Homo habilis, Homo erectus, Homo neanderthalensis, etc.), and these have overlapped in their existences, contrary to what you might've thought. And so it's the case that, just like today there are various species of ants, bears, and pigs all existing simultaneously, H. erectus, H. neanderthalensis, and H. sapiens all existed concurrently, at least briefly. Now, of course, they are all extinct save one: sapiens (see Harari 2015, chapter 1).

The species Homo sapiens emerged only between 300,000 and 200,000 years ago, relatively late in the 2 million year history of the genus. By about 150,000 years ago, however, sapiens had already populated Eastern Africa. About 100,000 years ago, Harari tells us, some sapiens attempted to migrate north into the Eurasian continent, but they were beaten back by the Neanderthals that were already occupying the region. This has led some researchers to believe that the neural structure of those sapiens (circa 100,000 years ago) wasn’t quite like ours yet. One possible theory, reports Harari, is that those sapiens were not as cohesive and did not display the kind of social solidarity required to band together and collectively overcome other species, such as H. neanderthalensis. But we know the story doesn't end there.

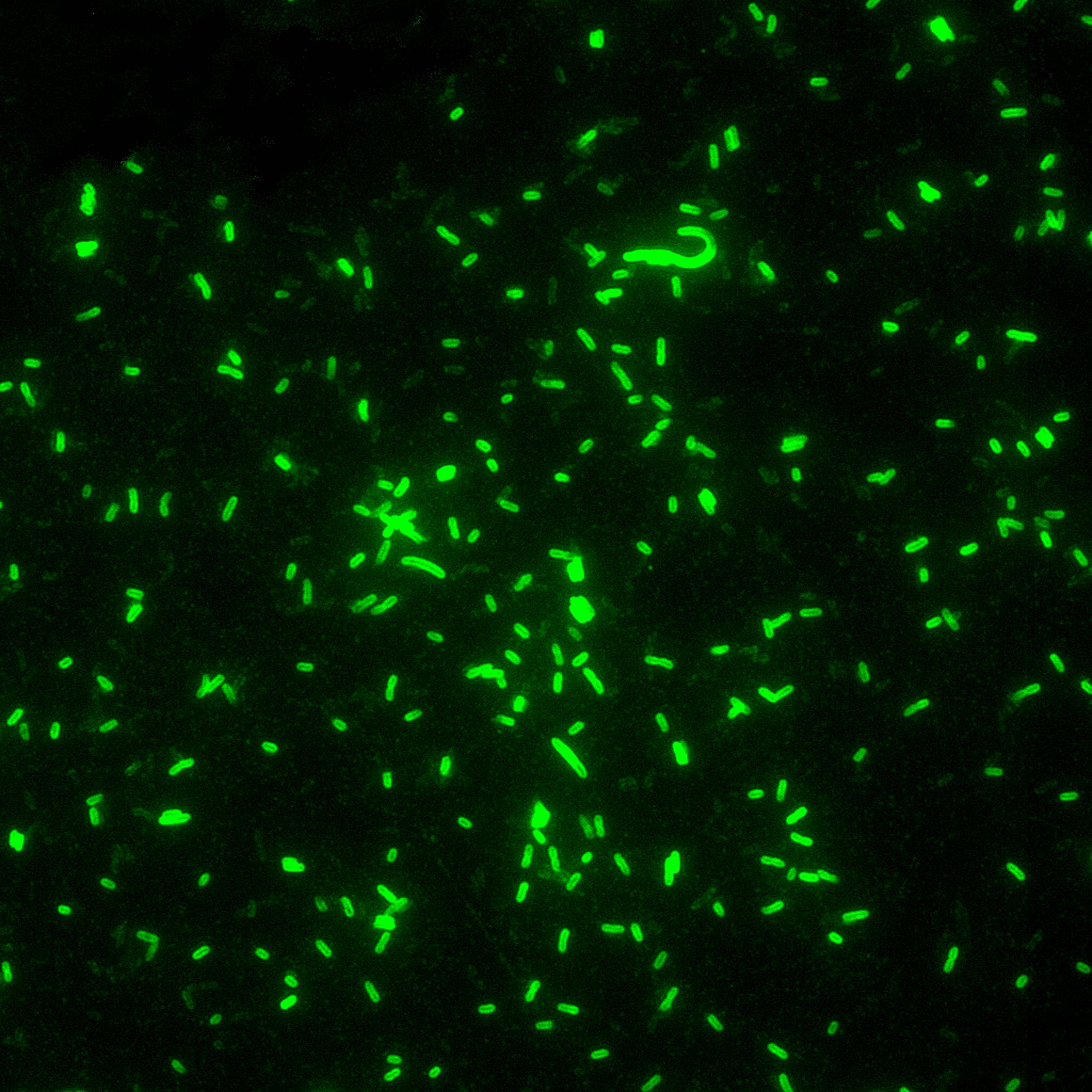

Around 70,000 years ago, sapiens migrated out of Africa again, and this time they beat out the Neanderthals. Something had changed. Something allowed them to outcompete other Homo species. What was it? Well, here's one theory. It was this time period, from about 70,000 to 40,000 years ago, that constitutes what some theorists call the cognitive revolution—although other theorists (e.g., von Petzinger 2017) push the start date back as far as 120,000 years ago.1 Regardless of the start date, it is tempting to suggest that it was the acquisition of advanced communication skills and the capacity for abstract thinking and symbolism that were somehow evolved during this time period that allowed sapiens to build more robust social groups, via the use of social constructs, and dominate their environment, to the detriment of other homo species (see Harari 2015, chapter 2). In short, sapiens grew better at working together, collaboratively and with a joint goal.2

The idea that sapiens acquired new cognitive capacities that allowed them to work together more efficiently is fascinating. It is so tempting to see these new capacities as a sort of social glue that allowed sapiens to outcompete, say, H. neanderthalensis. As anyone who has played organized sports knows: teams that work well together are teams that win. What makes this idea even more tempting is that this capacity for large-scale cooperation happened again. Between 15,000 to 12,000 years ago (the so-called Neolithic), sapiens’ capacity for collective action increased dramatically again, this time giving rise to the earliest states and empires. These are multi-ethnic social experiments with massive social inequalities that somehow stabilized and stayed together—at least sometimes. What is this social glue that allows for the sort of collectivism displayed by sapiens?

Two puzzles arise:

1. What happened ~100,000 years ago that allowed the successful migration of sapiens?

2. What happened ~15,000 years ago that allowed sapiens to once again scale up in complexity?

Perhaps evolutionary theory has the answer. Although many find it counterintuitive, the forces of natural selection have not stopped affecting Homo sapiens. Despite it being the case that sapiens today are more-or-less anatomically indistinguishable from the way they were 200,000 years ago, there have been other changes under the hood, so to speak. In fact, through the study of genomic surveys, Hawks (et al. 2007) calculates that over the last 40,000 years our species has evolved at a rate 100 times as fast as the previous evolution. Homo sapiens has been undergoing dramatic changes in its recent history.

It is, in fact, the father of evolutionary theory, Charles Darwin (1809-1882), pictured left, that first suggested that it was an adaptation, an addition to our cognitive toolkit, that allowed sapiens to work together more collaboratively and with more complex relationships. He tended to refer to this new capacity as making those "tribes" who have it more "well-endowed", giving them "a standard of morality", and, interestingly, he also posited that this wasn't an adaptation that occurred at the individual-level but rather at the level of the group.2 Here is an important passage from Darwin's 1874 The Descent of Man:

“It must not be forgotten that although a high standard of morality gives but a slight or no advantage to each individual man and his children over the other men of the same tribe, yet that an increase in the number of well-endowed men and an advancement in the standard of morality will certainly give an immense advantage to one tribe over another… and this would be natural selection. At all times throughout the world tribes have supplanted other tribes; and as morality is one important element in their success, the standard of morality and the number of well-endowed men will thus everywhere tend to rise and increase” (Darwin 1874 as quoted in Wilson 2003: 9).

And so, the intellectual heirs of Darwin's conjecture (e.g., Haidt 2012, Wilson 2003) suggest that it was cognitive revolutions that are likely responsible for what I'll be referring to as increases in civilizational complexity. For our purposes, civilizational complexity will refer to a. an increased division of labor in a given society and b. growing differences in power relations between members of that society (hierarchy/inequality), despite c. a constant or perhaps even increased level of social solidarity (cohesiveness). With this definition in place, we can see that hunter-gatherer societies were low in civilizational complexity (very little division of labor, very egalitarian) and a modern-day republic, say, Canada, is high in civilizational complexity (a basically uncountable number of different forms of labor, various social classes). Intuitively, the more egalitarian societies would seem more stable, but, with our new cognitive additions, sapiens can find social order in high-diversity, massively populated and massively unequal societies.

Does this solve our puzzles? Quite the contrary. Many more questions now arise. Why did sapiens develop this new capacity for complex communication? What kinds of communication and what kinds of ideas are available to sapiens now that weren't available to them before the cognitive revolution? What specific ideas led to the growth in civilizational complexity? Are there any pitfalls that accompany our new cognitive toolkit? Obviously, we're just getting started.

What's ethics got to do with it?

The puzzles above, which I hope you find engaging, to some theorists are clearly related to the phenomenon of ethics. In a tribe, team and society, there are right and wrong ways to behave, and the more people behave in the right ways, the more stable that society will be. Others argue that the evolutionary story of our capacity for competitive, complex societies, although interesting, is unrelated to ethics. I guess ultimately that really depends on what you mean by ethics. For starters, many people assume a distinction between ethics and morals. A simple internet search will yield funny little distinctions between these two. For example, one website3 claims that ethics is the code that a society or business might endorse for its members to follow, whereas morals is an individual's own moral compass. But this distinction already assumes so much. We'll be covering a theory in this class that tells you that the moral code society endorses is the only thing you have to abide by. This renders "your own morals" as superfluous. We'll also look at a view that argues that the only thing that matters is what you think is right for you, so what society claims doesn't matter. We'll even cover a view that argues that both what society endorses and what you think is right is irrelevant: morality comes from reason. So this distinction is useless for us since it assumes that we've already identified the correct ethical theory.

So then what is the study of ethics? Lamentably, there is no easy answer to this question. For many philosophers, to consider the origin of our cognitive capacities and how they allow us to work together more effectively is completely irrelevant to the field of ethics. For them, ethics is the study of universal moral maxims, the search for the answer to the question, "What is good?". For Darwin, as we've seen, it was perfectly sensible to call sapiens' capacity for collective action a 'moral' capacity. And, unfortunately, there are even more potential answers to the question "What is ethics?"

Thankfully, I have it on good authority that we don't need to neatly cordon off just what ethics is at the start. One of the most influential moral philosophers of the 20th century, Alasdair MacIntyre, begins his A Short History of Ethics by making the case that there is in reality a wide variety of moral discourses; different thinkers at different times have conceived of moral concepts—indeed the very goal of ethics—in radically different ways. It is not as if when Plato asked himself “What is justice?” he was attempting to find the same sort of answer that Hobbes was looking for when reflecting on the same topic. So, it is not only pointless but counterproductive to try to delimit the field of inquiry at the outset. In other words, we cannot begin by drawing strict demarcation lines around what is ethics and what is not.

If MacIntyre is correct, then the right approach is a historical one. We must place moral discourse in its historical context to understand it correctly. Moreover, this will allow us to see the continuity of moral discourse. It is the case, as you shall see, that one generation of ethicists influences the generation after them, and so one can see an "evolution" of moral discourse. This is the approach we'll take in this course. For now, then, when we use the word ethics, we'll be referring to the subfield of philosophy that addresses questions of right and wrong, the subfield that attempts to answer questions about morality.

You might be wondering what the field of philosophy is all about. I have a whole course that tries to answer that question. Let me give you my two sentence summary. There are two approaches to doing philosophy: the philosophy-first approach (which seeks fundamental truths about reality and nature independently and without the help of science) and the science-first approach (which uses the findings of science to help steer and guide its inquiries). The philosophy-first approach (Philosophy with a capital "p") was dominant for centuries but fell into disrepute with the more recent success of the natural sciences, thereby making way for the science-first approach (the philosophy with a lowercase "p" that I engage in)—although many philosophy-first philosophers still haven't gotten the memo that science-first is in. Obviously the preceding two sentences are a cartoonish summary of the history of philosophy, a history that I think is very instructive. The interested student should take my PHIL 101 course.

Important Concepts

Course Basics

Theories

What we're looking for in this course is a theory, one that (loosely speaking) explains the phenomenon of ethics/morality.5 Now it's far too early to describe all the different aspects of ethics/morality that we'd like our theory to explain, so let's begin by just wrapping our minds around what a theory is. My favorite little explanation of what a theory is comes from psychologist Angela Duckworth:

“A theory is an explanation. A theory takes a blizzard of facts and observations and explains, in the most basic terms, what the heck is going on. By necessity, a theory is incomplete: it oversimplifies. But in doing so, it helps us understand” (Duckworth 2016: 31).

There are some basic requirements to a theory, however; these are sometimes referred to as the virtues of theories. What is it that all good theories have in common? Keas (2017) summarizes for us:

“There are at least twelve major virtues of good theories: evidential accuracy, causal adequacy, explanatory depth, internal consistency, internal coherence, universal coherence, beauty, simplicity, unification, durability, fruitfulness, and applicability” (Keas 2017).

These theoretic virtues are best learned during the process of learning how to engage in science—a process I suspect that you are beginning since you are taking a class in my division, Behavioral and Social Sciences. However, we can highlight a few important theoretic virtues right now.

Symbol for the Illuminati,

protagonists in several

preposterous grand conspiracies.

For a theory to have explanatory depth means that a good theory has greater depth with regards to describing the chain of causation around a phenomenon. In other words, it explains not only the phenomenon in question but also various nearby phenomena that are relevant to the explanation of the phenomenon in question. Another important theoretic virtue is simplicity, or explaining the same facts as rival theories, but with less theoretical content. In other words, if two theories explain some phenomenon but one theory assumes, say, secret cabals intent on one-world government while the second does not, you should go with the second simpler theory. (Why assume crazy conspiracies when human incompetence can explain the facts just as well?!) This principle, by the way, is also known as Ockham's razor. Lastly, a good theory should have durability; i.e., a good theory should be able to survive testing and perhaps even accommodate new, unanticipated data.

Can we find a theory that explains the phenomenon of ethics/morality and has the abovementioned theoretic virtues? We'll see...

Philosophical jargon

For better or worse, some of the first inquiries into ethics/morality came from the field of philosophy. So, in order to learn about these first attempts to grapple with ethics, we'll have to learn some philosophical jargon. Thankfully, the theoretic virtues of philosophical theories often overlap with the theoretic virtues of social scientific theories. As such, let's begin with a theoretic virtue that is a fundamental requirement of any theory: logical consistency—or, as Keas puts it, internal coherence. As you learned in the Important Concepts, logical consistency just means that the sentences in the set you are considering can all be true at the same time. In other words, none of the sentences contradict or undermine each other. This seems simple enough when it comes to theories that are only a few sentences long. But we'll be looking at theories will lots of moving parts, and it won't be obvious which theories have parts that conflict with each other. Thus, we'll have to be very careful when assessing ethical theories for logical consistency.

One more thing about logical consistency: you care about it. I guarantee you that you care about it. If you've ever seen a movie with a plot hole and it bothered you, then you care about logical consistency. You were bothered that one part of the movie conflicted with another part. This is being bothered by inconsistency! Or else think about when one of your friends contradicts him/herself during conversation. If this bothers you as much as it bothers me, we can agree on one thing: consistency matters.

How do we know if one philosophical theory is better than another? For this, we'll have to look at one of the main forms of currency in philosophy: arguments. In philosophy, an argument is just a set of sentences given in support of some other sentence, i.e., the conclusion. Put another way, it is a way of organizing our evidence so as to see whether it necessarily leads to a given conclusion. You'll become very familiar with arguments as we progress through this course. For now, take a look at this example, comprised of two premises (1 & 2) and the conclusion (3). If you believe 1 & 2 (the evidence), then you have to believe 3 (the conclusion).

- All men are mortal.

- Socrates is a man.

- Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

Food for Thought...

Roadblocks: Cognitive Biases

For evolutionary reasons, our cognition has built-in cognitive biases (see Mercier and Sperber 2017). These biases are wide-ranging and can affect our information processing in many ways. Most relevant to our task is the confirmation bias. This is our tendency to seek, interpret, or selectively recall information in a way that confirms one’s existing beliefs (see Nickerson 1998). Relatedly, the belief bias is the tendency to rate the strength of an argument on the basis of whether or not we agree with the conclusion. We will see various cases of these in this course.

I'll give you two examples of how this might arise. Although this happened long ago, it still stands out in my memory. One student felt strongly about a particular ethical theory. This person would get agitated when we would critique the view, and we couldn't have a reasonable class discussion about the topic while this person was in the room. I later found out that the theorist who was highlighted in that theory worked in the discipline of anthropology, the same major that the student in question had declared. But the fact that the theorist who endorses a particular theory is in your field is not a good argument for the theory. In fact, I can cite various anthropologists who don't side with the theory in question. As a second example, take the countless debates that I've had with vegans about the argument from the Food for Thought section. There is an objection to that example every time I present it. Again, this is not to say that veganism is false or that animals don't have rights, or anything of the sort(!). But we have to be able to call bad arguments bad. And that is a bad argument. I'll give you good arguments for veganism and animal rights. Stay tuned.

As an exercise, try to see why the following are instances of confirmation bias:

- Volunteers given praise by a supervisor were more likely to read information praising the supervisor’s ability than information to the contrary (Holton & Pyszczynski 1989).

- Kitchen appliances seem more valuable once you buy them (Brehm 1956).

- Jobs seem more appealing once you’ve accepted the position (Lawler et al. 1975).

- High school students rate colleges as more adequate once they’ve been accepted into them (Lyubomirsky and Ross 1999).

By way of closing this section, let me fill you in on the aspect of confirmation bias which makes it a truly worrisome phenomenon. What's particularly worrisome, at least to me, is that confirmation bias and high-knowledge are intertwined—and not in the way you might think. In their 2006 study, Taber and Lodge gave participants a variety of arguments on controversial issues, such as gun control. They divided the participants into two groups: those with low and those with high knowledge of political issues. The low-knowledge group exhibited a solid confirmation bias: they listed twice as many thoughts supporting their side of the issue than thoughts going the other way. This might be expected. Here's the interesting (and worrisome) finding. How did the participants in the high-knowledge group do? They found so many thoughts supporting their favorite position that they gave none going the other way. The conclusion is inescapable. Being more informed—i.e., being of high intelligence in a given domain—appears to only amplify our confirmation bias (Mercier and Sperber 2017: 214).

Ethical theory

The first step in this journey is to look at various ethical theories. In this first unit, we will be focusing on seven classical ethical theories from the field of philosophy. Given how influential they are in contemporary ethical theory, you will likely feel some affinity for some aspects of these theories. In fact, you might be convinced each theory we cover is the right one, at least at the time that we are covering it. This might be even more so the case with the first one, which is an ambitious type of theory that attempts to bridge politics and ethics. Moreover, central to this view is the notion that humans naturally and instinctively behave in purely self-interested way, a view that many find to be intuitively true.

It's time to take a look at the pieces of the puzzle...

FYI

Supplemental Material—

- Reading: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Entry on Ethics, Section 2

- Reading: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Entry on Fallacies

Note: Most relevant to the class are Sections 1 & 2, but sections 3 & 4 are very interesting.

-

Text Supplement: Useful List of Fallacies

Related Material—

- Video: TEDTalk, Stuart Firestein: The pursuit of ignorance

- Podcast: You Are Not So Smart Podcast, Interview with Hugo Mercier

- Note: Transcript included.

Footnotes

1. Von Petzinger (2017) makes the case that studying the evolution of symbolism and the capacity for abstract thinking in human cognition can be furthered by her field of paleoanthropology. Throughout her book, she details how, contrary to early paleoanthropological theories, the capacity for symbolism didn’t start around 40,000 years ago but much earlier. Her work, as well as that of others, shows that consistently utilized, non-utilitarian abstract geometric patterns can be seen since at least about 100,000 years ago, and perhaps as far back as 120,000 years ago(!) in Africa. Her argument is that there was a surprising degree of conformity and continuity to the drawing of different signs across these time periods and across vast geographic locations. It’s even the case that some patterns grew and waned in popularity. This shows that sapiens were already cognitively modern.

2. What brought about the cognitive revolution is actually hotly disputed (see Previc 2009). In fact, some theorists argue that it doesn’t even strictly-speaking exist (see Ramachandran 2000).

3. The theory of group selection is far beyond the scope of this course. However, the interested student can refer to Wilson (2003) for a defense of it, as well as an application of the theory to the question of the evolutionary origins of religion.

4. The website in question is diffen.com. If the page I visited is representative of the quality of distinctions that it makes, then you should not at all trust this website.

5. In chapter 4 of Failure: Why science is so successful, Firestein makes the case that the concepts of hypothesis and theory are outdated and not actively used by any scientists he knows—he is a biologist himself. Instead, they’ve replaced the words hypothesis and theory with the concept of model, which has less of an air of finality; it’s more of a work in progress. This is because the process of forming a model is more in line with how science is actually done(!), as opposed to the "scientific method"—which Firestein rails against.

The Mind's I

“A man always has two reasons for what he does—

a good one and the real one.”

~J. P. Morgan

The Afflicted City

We begin our survey of ethical theories—or as I'll sometimes call them moral discourses—in more or less the order in which they appeared historically, sort of. The thing about some moral discourses is that they tend to come in and out of fashion, as you'll see in this lesson. Although we'll be covering more modern versions of them, the inspiration for the two theories we are covering today is ancient. This is because thinkers far back in the Western tradition have been thinking about why we behave in the way we do, why we build big cities, build empires; why we sometimes work together and at other times slaughter each other. We know that Western thinkers had theories about this because the works of some very important thinkers have survived to tell us about them. One such thinker is Plato (circa 425 to 348 BCE).

Plato wrote primarily in dialogue form. Typically his dialogues would take the form of an at least partly fictionalized dialogue between some ancient thinker and Plato's very famous teacher, Socrates. In Plato's masterwork Republic, the character of Socrates attempts to define justice while responding to the various objections of other characters, which expressed views that were likely held by some thinkers of Plato's time. In effect, this might be Plato's way of defending his view against competing views of the time, although there is some debate about this.

Barley bread.

In the dialogue, after some initial debate, the characters decide to build a hypothetical city, a city of words, so that during the building process they can study where and when justice comes into play. At first they build a small, healthy city. Everyone played their own role which served others. There was a housebuilder, a farmer, a leather worker, and a weaver so that they could have all the essentials. At this point, a character named Glaucon objected to the project. He argued that this is not a real city but it's a "city of pigs", a city where people would be satisfied with the bare minimum. A real city, with real people, would want luxuries and entertainment, and they would be dissatisfied with eating barley bread as their primary source of sustenance. So, at Glaucon's behest, the characters expanded the city to give its inhabitants the luxuries they likely wanted. Soon after, the characters realized the city would have to make war on its neighbors; they would need an army and they would need rulers.

Ground Rules

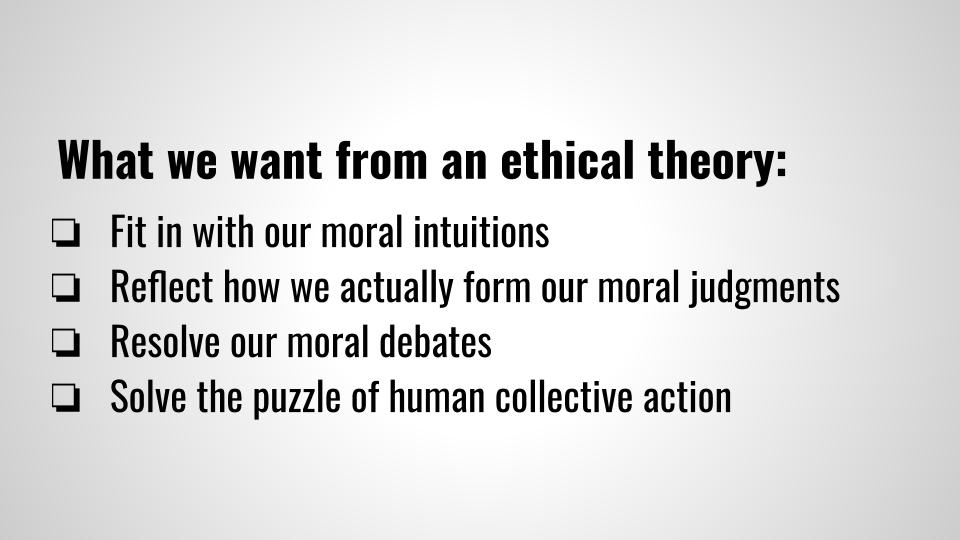

The way in which Plato's story proceeds after this point won't be covered here.1 Suffice it to say that Republic is one of the most influential documents in the history of political philosophy—and the story doesn't at all go in the direction you might think it does. In any case, what is relevant to us is the view endorsed by Glaucon, which we will take a closer look at in a moment. Before we do so, however, it is important to have ground rules for assessing ethical theories. I've made a checklist of some basic desiderata, i.e., things that we want, from an ethical theory. Let's review it briefly.

Ethical Theory Checklist

First off, we'd like an ethical theory that fits in with our moral intuitions. We don't want an ethical theory that mysteriously suggests that murder is ok. That would be a huge red flag. Next, we want an ethical theory that explains how we actually form moral judgments. If, for example, an ethical theory claims that we make our moral judgments by flipping a coin, then we know that ethical theory isn't very strong. Sure, maybe some people have done this, but making moral decisions seems to be more deliberate than that; it seems like we are usually very conflicted about how to proceed and wouldn't be satisfied by the outcome of a coin toss. Next, ideally we want an ethical theory that can resolve our moral debates. For example, some people think that capital punishment is morally abhorrent, while others think it is the proper thing for a society to do, to punish those who break its most fundamental laws. We'd like a theory that convincingly shows that one of these positions is right and the other is wrong. Lastly, we hope that the theory in question will help us shed light on how and why civilizational complexity has increased in the way that it has.

Important Concepts+

Glaucon's Challenge

Picking up where we left off, the characters in Plato's dialogue Republic begin to discuss how a luxurious city, one in which citizens would enjoy delicacies and splendor, would come into being. The need for this arose from what I will call Glaucon's challenge, a challenge I'm not sure Socrates ever satisfactorily responded to. The challenge has to do with the question of who is happier: the perfectly just person or the perfectly unjust person. In other words, Glaucon wants to know if it is better to be good or bad. He suggests that it might be better to be perfectly unjust, and he uses the story of the ring of Gyges to show just how advantageous being bad can be. In this story, a man comes into the possession of a ring which makes him invisible, and before long he has usurped a king and taken over his kingdom. Glaucon's challenge is this: show me that I'm wrong, show me that it is better to be just.

It is important to note that the sort of answer that Socrates, Glaucon and the others were looking for might not be what you would be looking for in a more modern context. MacIntyre (2003, chapter 8) draws a basic distinction between Greek ethics and modern ethics: Greek ethics is concerned with the question, “What am I to do if I am to fare well?” Modern ethics is concerned with the question, “What ought I to do if I’m to do right?” In other words, for the Greeks, being good and being happy where either the same thing or at least siblings. For many of us, though, doing good is not always what will make us happiest.

The Death of Patroclus.

To supplement this point, consider the history of the Greek word agathos, which is the ancestor of our word good. In Homeric times, the word was used to describe noblemen who were successful in battle and in ruling. It also implied that they had the wealth and status to be able to train so that they can be successful in battle and in ruling. These were the highest aim of a Greek. The attribution of agathos to others is inextricably linked to the descriptive: success in battle, wealth, etc. Notice, though, that these are not our highest aims now—at least for most of us, I think. For us, doing right thing is often very far from what is most personally advantageous. And so, what the Greeks meant by good is fairly distant from what most of us mean by it.

With this context in place, you can see that Socrates had his work cut out for him. Could he convince Glaucon that being just is better than being unjust? Well, as I've said, you'll have to read Republic on your own to find out. For our purposes, there are just a few things to note. First off, Glaucon seems to be assuming that pleasure is the only intrinsic good and that it would be rational to maximize our own pleasure. Moreover, he adds an important psychological insight—one that modern science has confirmed (Tversky and Kahneman 1991). It is this: we feel the bad more than the good. In psychological jargon, this is called loss aversion. Out of these assumptions, Glaucon builds his theory. Maybe we only band together to avoid even worse suffering. Maybe a long time ago we just agreed to not commit injustices against each other because that would be, on balance, better than constantly being at risk of having injustice committed against you. We came to the realization that it is better to live and let live than to always have to be on guard against others. This is Glaucon's case against justice: justice isn't an intrinsic good; it's just the best we can do.

“Hence, those who have done and suffered injustice and who have tasted both—the ones who lack the power to do it and avoid suffering it—decide that it is profitable to come to an agreement with each other neither to do injustice nor to suffer it. As a result, they begin to make laws and covenants; and what the law commands, they call lawful and just. That, they say, is the origin and very being of justice. It is in between the best and the worst. The best is to do injustice without paying the penalty; the worst is to suffer it without being able to take revenge. Justice is in the middle between these two extremes. People love it, not because it is a good thing, but because they are too weak to do injustice with impunity” (Republic, 359a).

Sidebar

Hobbes' Leviathan

As I mentioned in the Sidebar, moral discourses tend to go in and out of fashion. Just as Glaucon gave an account of justice that was based on a social contract, nearly two thousand years later, Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) would arrive at much the same conclusion.

Hobbes, like other philosophers of the period, had an interesting profession: a sort of live-in scholar for noblemen. The role left little time for marriage and family life, as is the case with both Hobbes and Locke, but allowed for intellectual and philosophical pursuits. Hobbes, in his role as servant to his first employer William Lord Cavendish, entailed functioning as a secretary, tutor, financial agent, and general advisor.

Hobbes' views on ethics/politics will seem very similar to the views of Glaucon, if Glaucon indeed held these views. They both assume hedonism and psychological egoism is true, and they claim that prosocial behavior is merely a state of affairs we submit to purely out of self-interest. Morality, they say, is convenient fiction. In short, we submit to an authority and give it a monopoly on violence because the alternative, the state of nature where everyone is at war with each other, is substantially worse. But remember: justice and morality are mere social contracts; if society collapses, you can feel free to ignore these contracts. We'll call this view social contract theory, or SCT for short.

“Hereby it is manifest that during the time men live without a common power to keep them all in awe, they are in that condition which is called war; and such a war as is of every man against every man... In such condition there is no place for industry, because the fruit thereof is uncertain: and consequently no culture of the earth; no navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by sea; no commodious building; no instruments of moving and removing such things as require much force; no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short” (Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, i. xiii. 9)

Hobbes and SCT

Is Hobbes' right? Certainly we have seen unthinkable acts of violence and theft when there is a breakdown in central authority. From the LA Riots in 1992 to involuntary euthanasia during the Hurricane Katrina disaster, and even more recently during the looting after the George Floyd protests.2 We will give a more careful assessment of SCT in the next lesson, but for now I want you to think about how the breakdown of central of authority is at least correlated with some instances of immorality and blatant disregard for the law. But Hobbes' theory mostly rests on one biological trait: psychological egoism. Is it truly the case that all human actions are driven by self-interest?

Food for Thought...

Ethical egoism

So our first theory, SCT, is based primarily upon the assumptions of hedonism and psychological egoism. Both have been challenged and we will look at those objections. However, before moving on to that, I'd like to introduce you to a close cousin of Hobbes' SCT: ethical egoism. Ethical egoism makes the same starting assumptions as Hobbes, but it is—perhaps we can say—less ambitious. It does not seek to explain how societies coalesce, or how the laws could stabilize social order, or any of Hobbes' more grandiose claims. Ethical egoism is much simpler: an action is right if, and only if, it is in the best interest of the agent performing the action. Here is a simple argument for the view.

- If the only way humans are able to behave is out of self-interest, then that should be our only moral standard.

- All human actions are done purely out of self-interest, even when we think we are behaving selflessly (psychological egoism).

- Therefore, our moral standard should be that all humans should behave purely out of self-interest.

Mandeville's

The Fable of the Bees.

In a nutshell, this argument states that if all we can do is behave in a self-interested way, that’s all we should do. Premise 1 seems reasonable enough. A thinker that we will come to know eventually, Immanuel Kant, argued that if we should do something then that implies that we can do it. Although Kant did not believe in psychological egoism, we can accept his dictum that we should be able to do what we are required do. This implies that if we can't help but to act in a self-interested way, then that's the only rational standard we should be held against.

Ayn Rand.

If it were up to me, I wouldn't even bother covering ethical egoism (EE for short). Hobbes' SCT almost seems to 'contain' EE, but is much better argued for. But I cover the view for two reasons. One is that, like SCT, this type of moral discourse has cropped up in history multiple times. In the early 18th century, for example, Bernard Mandeville advocated something very much like this view in his 1714 The Fable of the Bees. Then, in the 20th century, novelist and philosopher Ayn Rand endorsed greed as being good—a sentiment that is very much in line with ethical egoism.3

In any case, the proponents of ethical egoism argue that psychological egoism can explain all human actions. We can admit at least that it does seem to account for many of our behaviors. For one, sometimes people are selfish. Sometimes, however, people cooperate and behave in a seemingly altruistic way, which is to say for the benefit of others. Egoists claim their view can also account for this sort of behavior because it’s possible people behave this way only to: get the benefits of working cooperatively, or enjoy moral praise (from themselves and others), or just avoid feeling guilt. Let's be honest, some of you don't lie or steal simply because you couldn't bare the guilt.

Does ethical egoism meet our desiderata? Well it might fit with some of our moral intuitions. Most of us think that murder is wrong. An ethical egoist might agree given that the chances of being caught are pretty good, and being caught for murder is definitely not in our best interest. Does it reflect how we form our moral judgments? Maybe for some of us, but it's hard to say definitively that every one reasons in this way about moral matters. The egoist can push back, though. They might argue that even Mother Teresa acted in a self-interested way. After all, if her faith was well-placed, she did get a reward for her life's work: eternal bliss in heaven. Does it resolve our moral debates? Hardly. This is a definite setback for ethical egoism. Lastly, does it solve the puzzle of human collective action? Not really. It doesn't even address it.

And so we have our first two ethical theories: Hobbes' social contract theory and ethical egoism. I think you should begin to associate the views with the name of the relevant thinker, so try to think of Hobbes when I discuss SCT from now on. As for EE, you can either think of Mandeville or Rand, but, to be honest, I always think of the lead character from the show Breaking Bad, Walter White. SPOILER ALERT: Early on, he said he did it for his family. But anyone that got to the end of the series knows the truth: he did it for himself. And this brings me to the second reason why, despite my better judgment, I do indeed cover EE: some of you actually like the view.

The ethical theories covered today took as their starting point two assumptions. Hedonism is the view that pleasure is the only intrinsic good. In other words, a hedonist believes both that good is equivalent to pleasure and that there is no other thing that qualifies as good for its own sake. Psychological egoism is the view that all human actions are rooted in self-interest.

Thomas Hobbes, sounding very much like Glaucon in Plato's Republic, argued that all prosocial behavior is merely a state of affairs we submit to purely out of self-interest. In his social contract theory, morality is merley a convenient fiction. In short, we submit to an authority and give it a monopoly on violence because the alternative, the state of nature where everyone is at war with each other, is substantially worse.

Reflecting on Hobbes' theory for how we form moral judgments is illuminating. For Hobbes, moral judgments are formed by our feelings and emotions, which are themselves influenced by self-interest. Since the self-interest of individuals will drive them towards conflict with each other sooner rather than later, Hobbes suggests that a set of stabilizing laws—a sort of fictional but useful morality—be established so as to avert catastrophe.

Ethical egoism, flavors of hich seemed to be advocated by Bernard Mandeville and Ayn Rand, is simply the view that act is right if, and only if, it is in the best interest of the person doing the action. Under this way of thinking, many thing are technically morally permissible, including stealing if you can get away with it and helping others all your life so you can get into heaven.

FYI

Suggested Reading: Plato, The Republic, Book II

-

Note: Read from 357a to 367e.

TL;DR: The School of Life, POLITICAL THEORY: Thomas Hobbes

Supplemental Material—

- Video: Peter Millican, Introduction to Thomas Hobbes

Advanced Material—

-

Reading: Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Entry on Egoism, Sections 1 & 2

-

Reading: Thomas Hobbes, On the Social Contract

-

Reading: Plato, The Republic, Book IX

-

Book: James Coleman, Foundations of Social Theory

-

Note: This is a more modern treatment of what is now dubbed “rational choice theory.”

-

Footnotes

1. I cover Plato's Republic in some detail in my PHIL 105: Critical Thinking and Discourse.

2. I recommend the documentary LA 92 on the social injustice and unrest leading up to the LA riots.

3. Rand is most known for her novels, Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead. She called her ethical theory objectivism; however, we are using this label for another theory later on. What she meant by objectivism was that our lives are governed by some central pursuit, i.e., some objective. We will be using the label, however, to denote the view that moral terms are objective and mind-independent, i.e., existing independent of humans.

Eyes in the Sky

An unjust law is no law at all.

~St. Augustine

Making room...

Last time we covered two ethical theories: Hobbes' social contract theory (SCT) and ethical egoism (EE). Of these two, SCT is clearly the more ambitious theory. It seeks to explain both the origins of civil society and our moral judgments; and it grounds the theory in an account of human nature. This last point is, according to MacIntyre (2003: 121-145), Hobbes' lasting contribution to moral discourse: to point out that a theory of ethics has to be grounded in a valid account of human nature. Note, however, that MacIntyre is not agreeing with Hobbes that all of our behaviors are driven by our self-interested nature; rather, he is noting that if we are to produce a viable ethical theory, it must come in tandem with a theory of human nature.

SCT, at least in my way of looking at things, has an edge over EE in another way. In his influential Inventing Right and Wrong, John Mackie (1990) discusses how pervasive Social Contract Theory has been, spanning back millennia. It appears, then, that SCT is intuitively appealing. This is because something about human society, with its built-in complexity and it's hierarchy, seems out of place in nature; no other animals have achieved this level and kind of cooperation (although some insects have come close).1 Mackie acknowledges that it looks like there was a sudden organizing principle given to humans. Law, justice, and morality abruptly appear as mutual agreements to work together, a type of cooperation which is not seen elsewhere in the animal kingdom.

“This [SCT] is a useful approach, which has been stressed by a number of thinkers. There is a colourful version of it in Plato’s dialogue Protagoras, where the sophist Protagoras incorporates it in an admittedly mythical account of the creation and early history of the human race. At their creation men were, as compared with other animals, rather meagerly equipped. They had less in the way of claws and strength and speed and fur or scales, and so on, to enable them to find food and to protect them from enemies and the elements.... Finally Zeus took pity on them and sent Hermes to give men aidōs (which we can perhaps translate as ‘a moral sense’) and dikē (law and justice) to be the ordering principles of cities and the bonds of friendship” (Mackie 1990: 108).

But SCT has its detractors. Despite acknowledging its influence, many thinkers do not believe SCT is accurate or tells the whole story. For example, linguist and developmental psychologist Michael Tomasello (2014) believes that even if SCT is intuitively appealing, is wrong in at least two ways. First off, Tomasello argues that complex social arrangements in human groups could not have arisen due to contracts, since the very act of making contracts itself requires various social conventions. In other words, Tomasello thinks that Hobbes' SCT puts the cart before the horse. Contracts can't be the origin of civilizational complexity since they are only possible once a certain degree of civilizational complexity has already been achieved.

“Some conventional cultural practices are the product of explicit agreement. But this is not how things got started; a social contract theory of the origins of social conventions would presuppose many of the things it needed to explain, such as advanced communication skills in which to make the agreement” (Tomasello 2014: 86).

Second, Tomasello argues that certain psychological capacities would've needed to evolve before any contracts could be made. However, these requisite psychological capacities could not have arisen—or at least did not arise—in a species with purely egoistic motives. According to Tomasello's theory, it looks like the evolution of our capacity for language required that we first evolve the capacity to act for the benefit of others, at least sometimes. This is why human language is, more often than not, informative, in some sense: because we evolved to give truthful information to each other. In non-human primates, on the other hand, communication typically takes the form of imperatives, i.e., commands. And so, humans first evolved the capacity for non-egoistic motives along with language, and then humans started making contracts. In other words, a pillar of SCT, psychological egoism, might turn out to be false.

Tomasello's point is well-taken. But it gets worse if we look at data from other empirical disciplines. As Singer (2011: 3-4) points out, fossil finds show that five million years ago our ancestor Australopithecus africanus was already living in groups. So, Singer concludes, since Australopithecus did not have the language capacities and full rationality requisite for contracts, then it’s clear that contracts are not a necessary antecedent to social living, like Hobbes, Rousseau and others have argued.

Another criticism of SCT comes from the study of history. New evidence is leading deep history scholars to the conclusion that the earliest states could not hold their population; they had to use coercion to reinvigorate their pool of subjects. Scott (2017) attempts to dispel the notion that states came first, and then the state bureaucracy facilitated agriculture. Nothing could be further from the truth. Scott notes that there are instances of agriculture that pre-date the formation of states by as much 4,000 years, thereby discrediting the notion that state formation is what facilitated agriculture. And so, although the timeframes varied by region, in general, there was a several thousand year period during which humans were practicing agriculture, but there was not yet a centralized authority.

Scott explains that earlier scholars, not unreasonably, projected the aridity of Mesopotamia of recent history back to ancient times and figured only states could’ve facilitated this process. In other words, when we look at where the earliest states formed (Mesopotamia), we look at how dry it is now and figure that it's been dry all along. We naturally infer that only state bureaucracies could've arranged for the coordination needed to irrigate those lands. However, now we know, through climate science, that the region was not arid back then; we can see more clearly that agriculture came first, and then (for some other reason) came the earliest states.

If true, this looks like Hobbes' account of how early states formed is false. It was not a mutual agreement to establish a common authority; instead, it was more like a coalition of warlords who forced subjects to settle in their lands. We now call these warlords the government.2

“If the formation of the earliest states were shown to be largely a coercive enterprise, the vision of the state, one dear to the heart of such social contract theorists as Hobbes and Locke, as a magnet of civil peace, social order, and freedom from fear, drawing people in by its charisma, would have to be re-examined. The early state, in fact, as we shall see, often failed to hold its population. It was exceptionally fragile epidemiologically, ecologically, and politically, and prone to collapse or fragmentation. If, however, the State often broke up, it was not for lack of exercising whatever coercive powers it could muster. Evidence for the extensive use of unfree labor, war captives, indentured servitude, temple slavery, slave markets, forced resettlement in labor colonies, convict labor, and communal slavery (for example, Sparta’s helots) is overwhelming” (Scott 2017: 25-9; emphasis added).

All this to say that SCT has some problems. As of now, we are leaving the status of the truth of psychological egoism as an open question. And so we move towards another ethical theory, this one having to do with supernatural beings...

Divine Command Theory

Divine Command Theory (DCT) is easy to summarize. Just as it was the case with SCT, the moral discourse behind DCT goes back millennia. We will be covering the version of DCT that was most popular in the Middle Ages, as embodied in the work of William of Ockham (ca. 1287 to 1347). Nonetheless, it should be clear that there are hints of this view far back in the history of Philosophy, as evident in Plato's dialogue Euthyphro, as well as long after Ockham, as in the work of Martin Luther. The following is taken from Keele's (2010) intellectual biography of Ockham who begins his book with the historical and ideological context into which he was born.

Per Keele (2010: 27), DCT typically entails the following theses:

- God is the source of moral law.

- What God forbids is morally wrong.

- What God allows is morally permissible.

- The very meaning of “moral” is given by God’s commands.

In a nutshell, the divine command theorist argues that morality has no cause but God. Morality simply is what God has stipulated it to be.

The Strangeness of DCT

Some people initially don't see how counterintuitive DCT really is. They think they understand it, but they haven't thought the whole thing through. To show you the strange of implications of DCT, we can look at an ancient debate between Socrates and Euthyphro from Plato's dialogue Euthyphro. The setup of the dialogue is not terribly important (although you can watch this video if you are interested). The important part is that, in a conversation on what piety means, Socrates corners Euthyphro into a strange dilemma.

Stealing, which, according to

divine command theorists is

only wrong because God

said it is wrong.

To better understand this dilemma, let's do two things. First, let's not talk of "gods". The Greeks were polytheists, but most people reading this are probably not. We'll assume monotheism (belief in one god) here.3 Second, let's replace the word piety for morality. So then, the dilemma that Euthyphro finds himself in is that either he defines morality as being invented by God or he defines morality as independent of God (but still being a code that God wants you to follow).

The first option makes morality very strange. It makes it so that some actions are wrong only because God said so. Had God not said anything, they would've been permissible or even morally required. But it seems obvious some things, like murder, are wrong no matter what. The second option doesn't actually define morality. It just tells you that God isn't directly involved with its creation but that God still wants you to follow moral rules. The divine command theorist bites the bullet and chooses the first option.

“[For Ockham and other divine command theorists], God, by his absolute power, was so free that nothing was beyond the limits of possibility: he could make black white and true false, if he so chose: mercy, goodness, and justice could mean whatever he willed them to mean. Thus not only did God’s absolute power destroy all [objective] value and certainty in this world, but his own nature disintegrated [in terms of the capacity for rational reflection]; the traditional attributes of goodness, mercy and wisdom, all melted down before the blaze of his omnipotence” (Leff 1956: 34; interpolations are mine).

There are a two more ways in which DCT is strange. First off, it seems to trap believers in a maze of circuitous reasoning. How so? Notice that the divine command theorist argues that moral values can only be grounded in God’s commands. However, they also (typically) argue that God is good. But(!) the very meaning of good was established by God. And so, it seems as if God basically defined his way into being good. And so, there appears to be no non-circular way of arguing that God is in fact good.

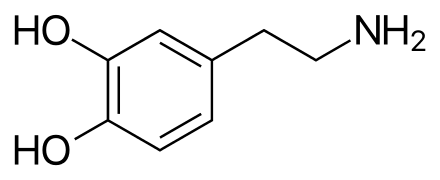

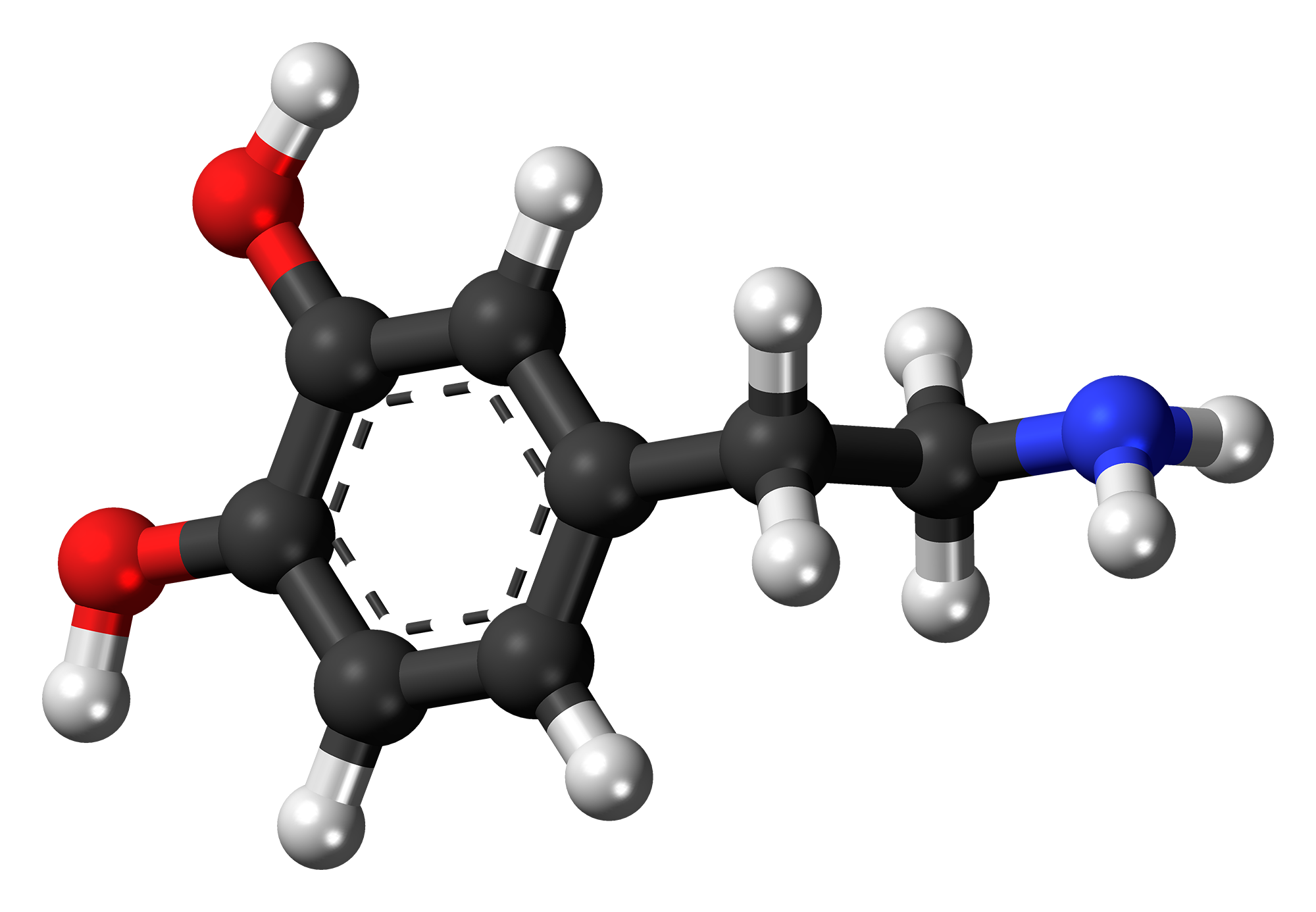

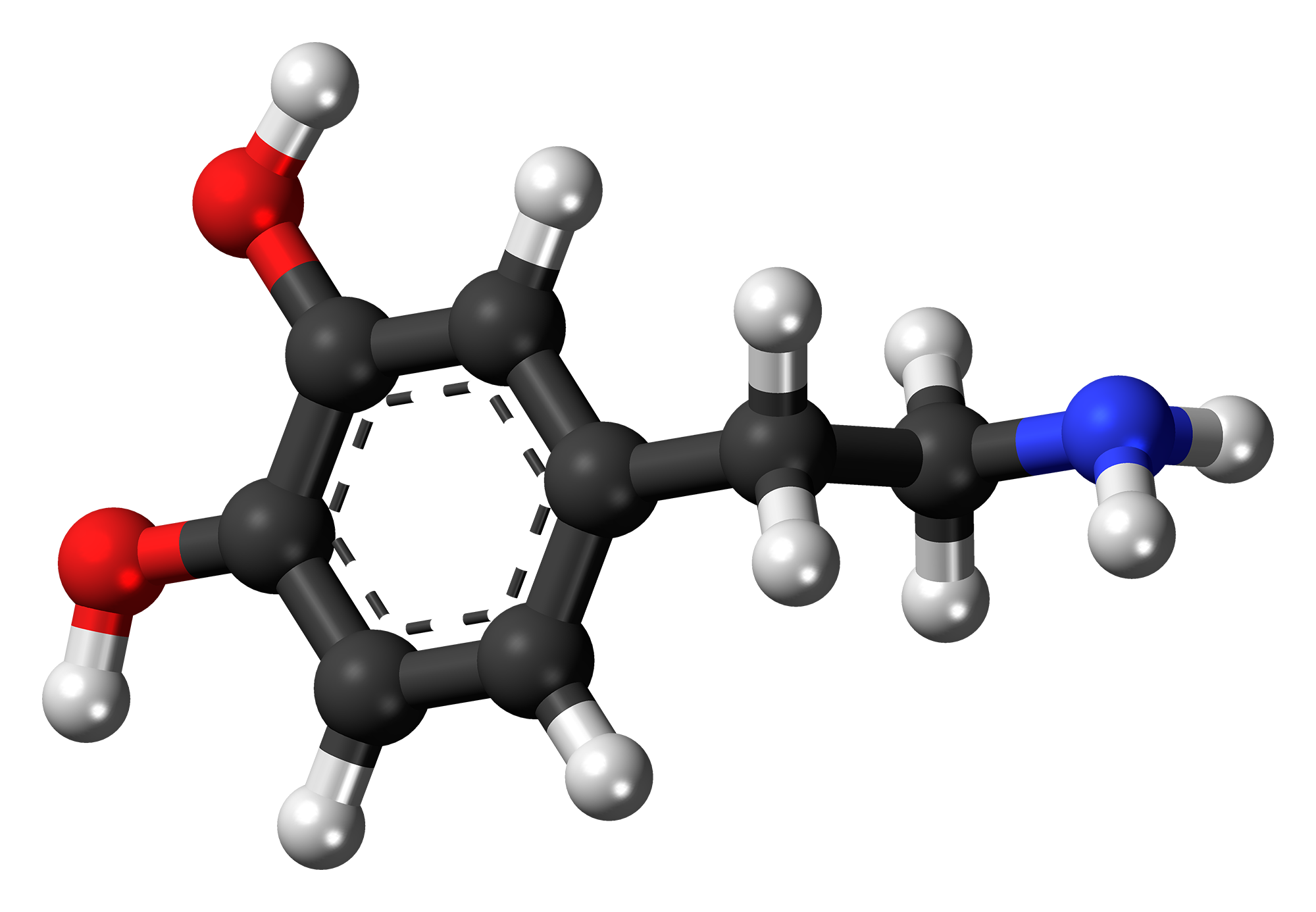

The third way in which DCT is strange is in what it makes out moral properties to be. Recall that for Hobbes and Glaucon, good could be equated with pleasure. Although this is questionable—as we will see when we cover David Hume—there is something appealing in this view, which we've been referring to as hedonism. What's appealing about hedonism is that it is a form of naturalism: the view that moral properties are natural properties. Why is this appealing? Because it certainly is the case that we at least know what pleasure is. We know it has to do with neurotransmitters in the brain, we know the kinds of things that give rise to pleasure (calorie-rich foods, sex, etc.), and we can come to know even more about it with the help of science. However, now think about what DCT says moral properties: they're actually God's commands. They are the proclamations of an all-powerful, supernatural being. Can you even begin to picture that? Can you really wrap your mind around understanding a divine command? If naturalism is true, then all is well and good; I can picture, say, dopamine. I even know it's chemical makeup (see image). But if DCT is true, then moral properties become a little less intelligible. Moral properties, in other words, turn out to be non-natural properties: non-physical, abstract, and invulnerable to being probed by the sciences.

Sidebar

An argument for DCT from moral properties

Interestingly enough, the strangeness of moral properties that DCT endorses could actually be used to motivate an argument in support of DCT. The argument is that non-naturalism gives the best account of why morality must be followed. Let me give you an example...

Imagine something you really think is morally wrong. Ok, now what if I ask you, "Why am I not allowed to do that thing?" What if you say, "Well, it's because it would make someone unhappy." If I were a real psychopath, I could say, "I kinda don't care." You try saying other things too. Maybe you'd tell me that it's not in my best interest, or that it is against the law. I can respond in the same way. "That doesn't matter to me." But what if instead you told me that there is an all-powerful being who told all of us that we cannot perform the action in question. Moreover, if I break this rule, I will suffer punishment for all eternity, I would live and re-live unthinkable horrors in a lake of fire. THAT might get me to think, "Hmmm... maybe this action shouldn't be done after all." There's something about moral predicates (like "______ is morally wrong") that assumes something supernatural is going on. It seems like the property of moral wrongness has not-to-be-done-ness built into it. It's hard to express this, but the idea is that, if you really believe something is morally wrong, you're likely not to do it. And it's hard to explain this with something simple and natural, like pleasure or the law. It's something else. Something divine.

Strange bed fellows...