Agrippa's Trilemma

Not to know what happened before you were born is to remain forever a child.

~Cicero

On the possibility of the impossibility of learning from history

There are so many cognitive traps when one is studying history. As we mentioned last time, we have biases operating at an unconscious level that don't allow us to perform an even-handed assessment of persons, ideas, products, etc. These biases might also disallow us from properly assessing a culture from the past (or even a contemporary culture that is very different from our own). In addition to this, however, it appears that we sapiens are surprisingly malleable with regards to the tastes and preferences that culture can bestow in us. Cultures, past and present, range widely on matters regarding humor, the family, art, when shame is appropriate, when anger is appropriate, alcohol, drugs, sex, rituals at time of death, and so much more.1

Recognizing our limitations, we have to always be cognizant of the boundaries of our intuition and of our prejudices. More than anything, we need to keep in check our unconscious desire to want to know how to feel about something right away. Whether it be some person, some practice, some event, or some idea, our mind does not like dealing in ambiguities; it wants to know how to feel right away.

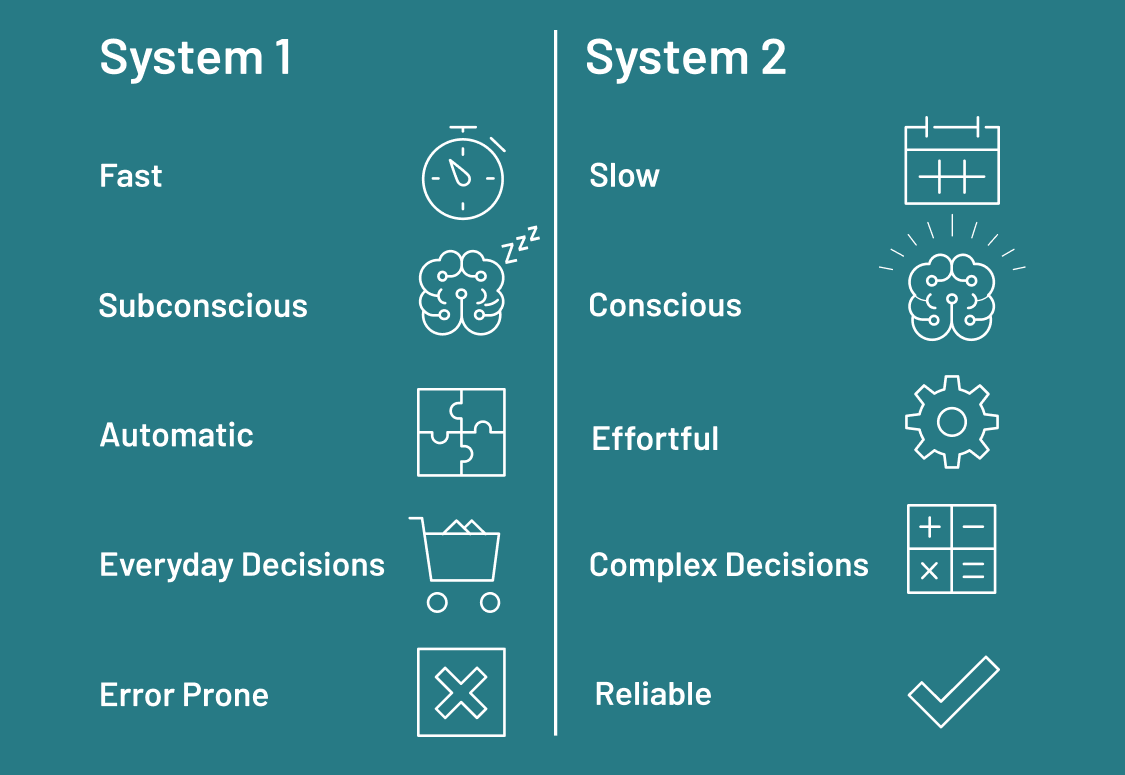

The psychological machinery that underlies all this is very interesting. The psychological model endorsed by Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman, known as dual-process theory, is illuminating on this topic. Although I cannot give a proper summary of his view here, the gist is this. We have two mental systems that operate in concert: a fast, automatic one (System 1) and a slow one that requires cognitive effort to use (System 2). Most of the time, System 1 is in control. You go about your day making rapid, automatic inferences about social behavior, small talk, and the like. System 2 operates in the domain of doubt and uncertainty. You'll know System 2 is activated when you are exerting cognitive effort. This is the type of deliberate reasoning that occurs when you are learning a new skill, doing a complicated math problem, making difficult life choices, etc.2

How is this related to the study of history? Here is what I'm thinking. It appears that cognitive ease, a mental feeling that occurs when inferences are made fluently and without effort (i.e., when System 1 is in charge) makes you more likely to accept a premise (i.e., to be persuaded). In fact, it's been shown that using easy-to-understand words increases your capacity to persuade (Oppenheimer 2006). On the flip side, cognitive strain increases critical rigor. For example, in one study, researchers displayed word problems with bad font, thereby causing cognitive strain in subjects (since one has to strain to see the problem). Fascinatingly, this actually improved their performance(!). This is due to the cessation of cognitive ease and the increase of cognitive strain, which kicked System 2 in to gear (Alter et al. 2007).

It is even the case that cognitive ease is associated with good feelings. When researchers made it so that images are more easily recognizable to subjects (by displaying the outline of the object just before the object itself was displayed), they were able to detect electrical impulses from the facial muscles that are utilized during smiling (Winkielman and Cacioppo 2001).3

The long and short of it is that if you are in a state of cognitive ease, you'll be less critical; if you are in a state of cognitive strain, you've activated System 2 and you are more likely to be critical.

Thus, when you hear or read about cultural practices that are very much like your own, you often unquestioningly accept them, since you are in a state of cognitive ease. However, when you read about cultural practices (or ideas or whatever) that are very much unlike your own, this increases cognitive strain. Because of this, we are more likely to be critical about such practices (or ideas, etc.). Of course, it is ok to be critical, but we are often overly critical, applying a strict standard that we don't apply to our own culture. Moreover, this is compounded by the halo effect. We've found one thing we don't like about said culture, and so we erroneously infer the whole culture is rotten.

I'm not, of course, saying that this effect manifests itself in everyone all the time, or even in some people all the time. But it is a possible cognitive roadblock that might arise when you are going through the intellectual history that we'll be going through.

High-water mark

We'll begin our story soon, but let me give you two bits of historical context. The first has to do with the recent memory of the characters in our story. We will begin our story next time in the year 1600, but to begin to understand why the thinkers we are covering thought the way they did, you have to first know what they had seen, what their parents had seen, what they had been raised to accept. The 16th and early 17th centuries were, in my assessment, the high-water mark of religiosity in Europe. This period was characterized by a religious conviction that is only rivaled, to my mind, by the brief period of Christian persecution at the hands of the Romans under Nero.4

I am not alone in believing that this period stands out. In their social history of logic, Shenefelt and White (2013: 125-130) discuss the religious fanaticism of the 16th and 17th centuries, which are stained with wars of religion. The wars of this time period included the German Peasant Rebellion in 1524 (shortly after Martin Luther posted his Ninety-five Theses in 1517), the Münster Rebellion of 1534-1535, the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre (1572), and the pervasive fighting between Catholics and Protestants that culminated in the Thirty Years War (1618-1648). Shenefelt and White also discuss how these events inspired some thinkers to argue that beliefs needed to be supported by more than just faith and dogma. Thinkers became increasingly convinced that our beliefs require strong foundations. My guess is that if you lived through those times, you would've likely been in shock too. You would've longed for a way to restore order.

And so this is why I call this the high-water mark of religiosity. But notice that embedded in this claim is a very improper implication. By saying that this was the highest point of religious fervor in the West, and by grouping (most of) you into the greater Western tradition, I'm implying that these 16th and 17th century believers were more religious than you are (if you are religious). How very devious of me! Notwithstanding the outrage that many have expressed when I say this, I stand by my claim. It really does seem to me that the religious commitment of 16th and 17th century Christians was stronger than that of Christians today.

At this point, we could get into a debate about what religious commitment really is; or how the institution that one is committed to might change over the centuries so that commitment looks different in different time periods. I'd love to have those conversations. My general argument would be that the standards of what it meant to be a believer back then were higher than the standards of today (where going to a service once a week suffices for many). But without even getting deep into that, let's just look at the behavior of believers 400 years ago. Maybe once you learn about some of their practices, you'll side with me.

When I first wrote this lesson, I knew I needed something shocking to show you just how different things were in the early modern period in Europe. And, to be honest, I didn't think for too long. I knew right away what would drop your jaw. I'm going to describe for you an execution, in blood-curdling detail—an execution steeped in religious symbolism and where the "audience" was sometimes jealous of the person being tortured and executed.

Stay tuned.

Important Concepts

Distinguishing Deduction and Induction

As you saw in the Important Concepts, I distinguish deduction and induction thus: deduction purports to establish the certainty of the conclusion while induction establishes only that the conclusion is probable.5 So basically, deduction gives you certainty, induction gives you probabilistic conclusions. If you perform an internet search, however, this is not always what you'll find. Some websites define deduction as going from general statements to particular ones, and induction is defined as going from particular statements to general ones. I understand this way of framing the two, but this distinction isn't foolproof. For example, you can write an inductive argument that goes from general principles to particular ones, like only deduction is supposed to do:

- Generally speaking, criminals return to the scene of the crime.

- Generally speaking, fingerprints have only one likely match.

- Thus, since Sam was seen at the scene of the crime and his prints matched, he is likely the culprit.

I know that I really emphasized the general aspect of the premises, and I also know that those statements are debatable. But what isn't debatable is that the conclusion is not certain. It only has a high degree of probability of being true. As such, using my distinction, it is an inductive argument. But clearly we arrived at this conclusion (a particular statement about one guy) from general statements (about the general tendencies of criminals and the general accuracy of fingerprint investigations). All this to say that for this course, we'll be exclusively using the distinction established in the Important Concepts: deduction gives you certainty, induction gives you probability.

In reality, this distinction between deduction and induction is fuzzier than you might think. In fact, recently (historically speaking), Axelrod (1997: 3-4) argues that agent-based models, a new fangled computer modeling approach to solving problems in the social and biological sciences, is a third form of reasoning, neither inductive nor deductive. As you can tell, this story gets complicated, but it's a discussion that belongs in a course on Argument Theory.

Food for Thought...

Alas...

In this course we will only focus on deductive reasoning, due to the particular thinkers we are covering and their preference for deductive certainty. Inductive logic is a whole course unto itself. In fact, it's more like a whole set of courses. I might add that inductive reasoning might be important to learn if you are pursuing a career in computer science. This is because there is a clear analogy between statistics (a form of inductive reasoning) and machine learning (see Dangeti 2017). Nonetheless, this will be one of the few times we discuss induction. What will be important to know for our purposes, at least for now, is only the basic distinction between the two forms of reasoning.

Assessing Arguments

Some comments

Validity and soundness are the jargon of deduction. Induction has it's own language of assessment, which we will not cover. These concepts will be with us through the end of the course, so let's make sure we understand them. When first learning the concepts of validity and soundness students often fail to recognize that validity is a concept that is independent of truth. Validity merely means that if the premises are true, the conclusion must be true. So once you've decided that an argument is valid, a necessary first step in the assessment of arguments, then you proceed to assess each individual premise for truth. If all the premises are true, then we can further brand the argument as sound.6 If an argument has achieved this status, then a rational person would accept the conclusion.

Let's take a look at some examples. Here's an argument:

- Every painting ever made is in The Library of Babel.

- “La Persistencia de la Memoria” is a painting by Salvador Dalí.

- Therefore, “La Persistencia de la Memoria” is in The Library of Babel.

At first glance, some people immediately sense something wrong about this argument, but it is important to specify what is amiss. Let's first assess for validity. If the premises are true, does the conclusion have to be true? Think about it. The answer is yes. If every painting ever is in this library and "La Persistencia de la Memoria" is a painting, then this painting should be housed in this library. So the argument is valid.

But validity is cheap. Anyone who can arrange sentences in the right way can engineer a valid argument. Soundness is what counts. Now that we've assessed the argument as valid, let's assess it for soundness. Are the premises actually true? The answer is: no. The second premise is true (see the image below). However, there is no such thing as the Library of Babel; it is a fiction invented by a poet. So, the argument is not sound. You are not rationally required to believe it.

Here's one more:

- All lawyers are liars.

- Jim is a lawyer.

- Therefore Jim is a liar.

You try it!7

Pattern Recognition

The second bit

I said we needed two bits of historical context before proceeding. I gave you one: the high-water mark of religiosity. Here's the other.

In 1600, the Aristotelian view of science still dominated. Intellectuals of the age saw themselves as connected to the ancient ideas of Greek and Roman philosophers. It's even the case that academic works were written in Latin. So, in order to understand their thoughts, you have to know a little bit about ancient philosophy. Enjoy the timeline below:

Storytime!

There is one ancient school of philosophy that I'd like to introduce at this point. I'm housing this section within a Storytime! because very little is known about the founder of this movement. For all I know, none of what I've written in the next paragraph is true. Here we go!

Pyrrho (born circa 360 BCE) is credited as the first Greek skeptic philosopher. It is reputed that he travelled with Alexander (so-called "the Great") on his campaigns to the East. It is there that he came to know of Eastern mysticism and mindfulness. And so he came back a changed man. He had control over his emotions and had an imperturbable tranquility about him.

Here's what we do know. He was a great influence on Arcesilaus (ca. 316-241 BCE) who eventually became a teacher in Plato's school, the Academy. Arcesilaus' teachings were informed by the thinking of Pyrrho, and this initiated the movement called Academic Skepticism, the second Hellenistic school of skeptical philosophy. This line of thinking continued at least into the third century of the common era.

Skepticism is a view about knowledge, namely that we cannot really know anything. The branch of philosophy that focus on matters regarding knowledge is epistemology. You'll learn more about that below in Decoding Epistemology.

Decoding Epistemology

The Regress Argument

Although Pyrrhonism is interesting in its own right, we won't be able to go over its finer details here. In fact, we will only concern ourselves with one argument from this tradition. In effect, the last piece of the puzzle in our quest for context will be the regress argument, a skeptical argument whose conclusion states that knowledge is impossible. The regress argument, by the way, is also known as Agrippa’s Trilemma, named after Agrippa the Skeptic (a Pyrrhonian philosopher who lived from the late 1st century to the 2nd century CE).

To modern ears, the regress argument seems like a toy argument. It seems so far removed from our intellectual framework that it is easy to dismiss. But, again, this is easy for you to say. You are, after all, reading this on a computer. You are assured that the state of knowledge of the world is safe. You didn't live through the Peloponnesian War, or the fall of the Roman Empire, or the Thirty Year's War. You are comfortable that science will progress, perhaps indefinitely. In other words, you don't really think that collapse is possible for your civilization. But thinkers of the past didn't have this luxury. They were concerned with basic distinctions like, for example, the distinction between knowledge and opinion.8

As such, try to be charitable when you read this argument. Today, epistemology, the branch of philosophy concerning knowledge, is more like a game that epistemic philosophers play. But in the ancient world, when the notion of rational argumentation was still in its infancy, the possibility that perhaps we can never really know anything (i.e., skepticism) was a real threat.

The argument

- In order to be justified in believing something, you must have good reasons for believing it.

- Good reasons are themselves justified beliefs.

- So in order to justifiably believe something, you must believe it on the basis of an infinite amount of good reasons.

- No human can have an infinite amount of good reasons.

- Therefore, it is humanly impossible to have justified beliefs.

- But knowledge just is justified, true belief (the JTB theory of knowledge).

- Therefore, knowledge is impossible.

The general idea is quite simple. Consider a belief, say, "My dog is currently at home". How do you know that belief is true? You might say, "Well, she was home when I left the house, and, in the past, she's been home when I get back to the house." A skeptic would probe further. "How do you know that today won't be the exception?" the skeptic might ask. "Perhaps today's the day she ran away or that someone broke in and stole her." You give further reasons for your beliefs. "Well, I live in a safe neighborhood, so it's unlikely that anyone broke in" and "She's a well-behaved dog so she wouldn't run away" are your next two answers. But the skeptic continues, "But even safe neighborhoods have some crime. How can you be sure that no crime has occurred?" Eventually, you'd get tired of providing support for your views. Even if you didn't, it's impossible for you to continue this process indefinitely (since you live only a finite amount of time). If knowledge really is justified, true belief, then you could never really justify your belief, because every justification needs a justification. I made a little slideshow for you of the "explosion of justifications" required, where B is the original belief and the R's are reasons (or justification) for that belief. Enjoy:

According to Agrippa, you have three ways of responding to this argument (and none of them work):

- You can start providing justifications, but you’ll never finish.

- You could claim that some things don’t need further justification, but that would be a dogma (which is also unjustified).

- You could try to assume what you are trying to prove, but that’s obviously circular.

The third possibility that Agrippa points out is definitely not going to work. In fact, that form of reasoning is considered an informal fallacy, which brings us to the...

Begging the Question

This is a fallacy that occurs when an arguer gives as a reason for his/her view the very point that is at issue.

Shenefelt and White (2013: 253) give various examples of how this fallacy appears "in the wild", but the main thread connecting this is the circular nature of the reasoning. For example, say someone believes that (A) God exists because (B) it says so in the Bible, a book which speaks only truth. They might also believe that (B) the Bible is true because (A) it comes from God (whom definitely exists). Clearly, this person is reasoning in circles.

An even more obvious example is a conversation I overheard in a coffee shop once. One person said, "God exists. I know it, man." His friend responded, "But why do you believe that? How do you know that God exists?" The first person, without skipping a beat, said, "Because God exists, bro." Classic begging the question.

Two more things...

Now that you know about the high degree of religiosity and some tidbits about ancient philosophy, the setup is complete. We can begin to move towards 1600. Let me just close with two points. First, I know I left you hanging last time. Let me correct that now. The fundamental question of the course is: What is knowledge? I know it doesn't seem like it could take the whole term to answer this question, but you'd be surprised.

Second, that execution that I mentioned... Don't worry. It's coming.

There are two important bits of context that are important to understand the history being told in this class:

- The first century of the early modern period in Europe (1500-1800 CE) was characterized by a high degree of religiosity;

- There was still an active engagement between the thinkers of this early modern period and the philosophies of ancient Greece.

The distinction between deduction (which purports to give certainty) and induction (which is probabilistic reasoning) is important to understand.

The jargon (i.e., technical language) for the assessment of arguments, namely the concepts of validity and soundness are essential to know.

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that concerns itself with questions relating to knowledge.

The ancient philosophical schools of skepticism posed challenges to the possibility of having knowledge which early modern thinkers were still thinking about and working through.

The regress argument, one argument from the skeptic camp, questions whether we can ever truly justify our beliefs, thereby undermining the possibility of having knowledge (at least per the definition of knowledge assumed in the JTB theory of knowledge).

FYI

Suggested Reading: Harald Thorsrud, Ancient Greek Skepticism, Section 3

TL;DR: Jennifer Nagel, The Problem of Skepticism

Supplementary Material—

-

Video: Steve Patterson, The Logic Behind the Infinite Regress

Related Material—

-

Video: Nerwriter1, The Death of Socrates: How To Read A Painting

Advanced Material—

-

Reading: A. J. Ayer, What is Knowledge?

Footnotes

1. To add to this, there was a major philosophical debate in the 20th century over the possibility of translation (e.g., see Quine 2013/1960). Consider how, in order to translate the modes of thought and concepts of an alien culture, you need to first interpret them. But the very process of interpretation is susceptible to a misinterpretation—distortion due to unconscious biases. Perhaps the whole process of translation itself is doomed.

2. The interested student should consult Kahneman's 2011 Thinking, fast and slow or watch this helpful video.

3. Zajonc argues that this trait, to find the familiar favorable, is evolutionarily advantageous. It makes sense, he argues, that novel stimuli should be looked upon with suspicion, while familiar stimuli (which didn’t kill you in the past) can be looked on favorably (Zajonc 2001).

4. Emperor Nero took advantage of the Great Fire of 64 CE to build a great estate. Facing accusations that he deliberately caused the fire, he heaped the blame on the Christians, and a short campaign of persecution began. However, the Christians appeared to revel in the persecution. Martyrdom allowed many who were otherwise of lowly status or from a disenfranchised group (like women or slaves) to become instant celebrities and be guaranteed, they believed, a place in heaven. Martyrdom literature proliferated, and Christians actively sought out the most painful punishments (see chapter 4 of Catherine Nixey's The Darkening Age).

5. By the way, I'm not alone in using this distinction. One of the main books I'm using in building this course is Herrick (2013) who shares my view on this distinction.

6. Another common mistake that students make is that they think arguments can only have two premises. That's usually just a simplification that we perform in introductory courses. Arguments can have as many premises as the arguer needs.

7. This argument is valid but not sound, since there are some lawyers who are non-liars—although not many.

8. Interestingly, in an era of disinformation where there is non-ironic talk of "alternative facts" and "post-truth", the distinction between knowledge and opinion is once again an important philosophical distinction to make.