All Against All

A man always has two reasons for what he does—a good one and the real one.

~J. P. Morgan

The Puzzle of prosociality

Cooperation is actually quite common in nature. This is perplexing to us today given that we are often taught that evolution means "survival of the fittest"; we're told that nature is red in tooth and claw. This conception of natural selection seems to be the exact antithesis of cooperation, and so it would seem that competition should be the norm and cooperation should be very rare. But this is not the case. Across the animal kingdom, animals live in both short-term cooperative groups (like herds, flocks of migrating birds, etc.) and long-term cooperative groups (troops of non-human primates, human societies). Cooperation is actually widespread (Rubenstein and Kealey 2010).

Evolutionary theory can account for cooperation in nature, as you will see below, but a naive conception of the view will not lend itself to an understanding of the evolution of cooperation. And so, part of the reason why cooperation seems to be at odds with evolution is that evolution is poorly understood. There are many reasons for this. First off, and this shouldn't be surprising at this point, the teaching of evolutionary theory is often over-simplified in the USA during k-12 education. This is, at least in part, because evolutionary theory really is very complicated. It has been mathematized since Darwin introduced the view (Smith 1982), and there really are many conceptual issues—dare I say philosophical issues?—in biology that need to be worked out (Sober 1994). There's also the fact that, depressingly, as of 2019, 40% of Americans surveyed don't believe in evolution. And so, students often don't get a good grasp on evolutionary theory until college—if ever.

Even if one achieves a more nuanced understanding of evolutionary theory, however, the evolution of cooperation, also referred to as prosociality, is a complicated matter (Axelrod 1997). Cooperation arises for multiple reasons. For example, one reason for cooperation in nature is captured by theory of reciprocal altruism (Trivers 1971). The theory is simple. Consider a small group of animals that has some natural predator. One animal, because he is perched in a good position to see what's going on, sees the group's predator approaching in the sky. This animal could alert his groupmates, but this would alert the predator of his location. Should he take this risk, even if it's a small one, to alert his groupmates? Not alerting the group is in his own best interest in the short-term. However, he runs the risk of not receiving help from his group in the future for failing to alert the group about the predator now. So in this situation, where social interaction is long-term and repeated, the individual does have an incentive to take a risk for the rest of the group. And so, he behaves cooperatively and alerts the group of the predator's approach. Obviously, the calculations are not linguistic or conscious in most animals. The behavior is programmed into its genes. That's reciprocal altruism.

Honeypot ants.

Another form of cooperation is driven by the genetics of kin altruism. This is an evolutionary strategy that favors the reproductive success of one’s relatives and which can be seen in Hymenoptera (ants, bees, wasps), termites, and naked mole rats. In these creatures, the foundation of their ultrasocial cooperation is that they are all siblings, and it could lead to surprisingly self-less behavior. For example, some members of one species of ants spend their lives hanging from the top of a tunnel offering their abdomens as food storage bags for the rest of the nest. This ultrasociality bred ultracooperation, which is what enables the massive division of labor seen in these species.

Humans are also ultrosocial and ultracooperative, like ants. Unlike ants, though, we are not all relatives. Surely reciprocal altruism and kin selection play a role in our cooperative behavior, but there must be more to the explanation. Humans live in large-scale, hierarchical societies with a tremendous division of labor, and it doesn't seem like reciprocal altruism and kin selection alone can explain this. We love our social groups, and some willingly die for their groups. What is going on here?

“Humans invest time and effort in helping the needy within their community and make frequent anonymous donations to charities. They come to each other's aid in natural disasters. They respond to appeals to sacrifice themselves for their nation in wartime. And, they put their lives at risk by aiding complete strangers in emergency situations. The tendency to benefit others—not closely related—at the expense of oneself, which we refer to here as altruism or prosocial behavior, is one of the major puzzles in the behavioral sciences” (Van Vugt and Van Lange 2006: 237-8).

And so it seems that evolution can explain some forms of cooperation. But ultracooperation of the kind that humans engage in is more difficult to understand, and there are various proposed theories to explain this (e.g., Turchin 2015, Haidt 2012). However, it is unclear which theory is true. Call this the puzzle of prosociality.

Some students are initially unconvinced that humans are prosocial and cooperative at all. They argue that humans constantly go to war with each other, and that's not cooperation. War is actually an interesting example of the human capacity for ultrasociality. Just try to imagine one group of dogs getting together to go to war with another group of dogs. Some dogs make weapons, others train to fight, others make plans, and still others working on all the necessary resources for waging war, like making uniforms and securing food and water supplies. The imagery here should make you smile. You can't even really imagine it. This is because the whole idea of organized warfare requires a psychological capacity that dogs don't have: one that turns the individual into a nameless soldier beholden to the orders of a general. Humans sacrifice their lives and kill people they would've otherwise never met for their group. In fact, waging war is one of the most groupish, as opposed to selfish, things that we do. Some (Turchin 2015) even think that war is what made the modern world. I won't get into Turchin's views here, but just think of this. Human cooperation doesn't mean that everyone treats literally everyone with respect. It means that humans will sacrifice their own interests for the interests of their group. They'll even travel to faraway places and kill strangers for their group—true loyalty (or blind obedience?) to the group. More in the Storytime! below.

Storytime!

An Argument for Free Will via Moral Responsibility

In the last lesson, we saw the mounting threats to libertarian free will. We also saw that compatibilist free will is a non-starter if we want to solve the problem of evil. And so, in an attempt to preserve libertarian free will somehow, we turn to a discussion of morality. To many, the idea of morality seems real; it's not just an idea that humans made up. This is moral realism, also known as moral objectivism. This view, however, seems to only make sense if we have free will. And so, perhaps we can argue for libertarian free will by defending moral realism. Here's the argument:

- If humans do not have (libertarian) free will, then we cannot justifiably hold each other morally responsible for our morally wrong actions.

- But we do justifiably hold each other morally responsible for our morally wrong actions; i.e., some actions really are morally wrong and it is right to hold people accountable if they perform these actions.

- Therefore, it must be the case that we do have free will.

Naturally, this argument relies on the truth of moral realism, or something like it. And so, we turn next to ethical theory, a subfield of philosophy concerned with arriving at a system for telling what actions are morally wrong and which actions are morally permissible.

The Afflicted City

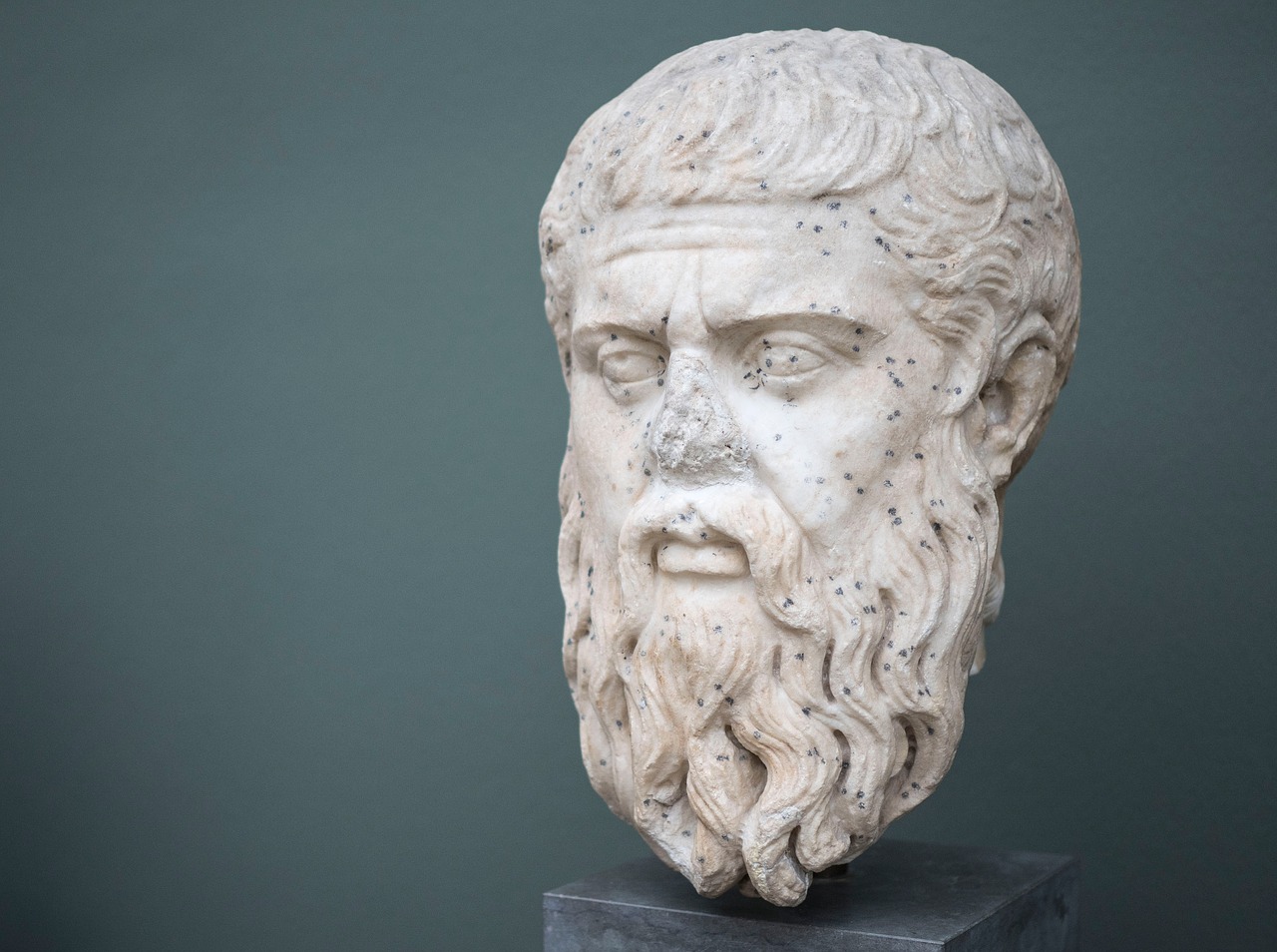

We begin our survey of ethical theories in more or less the order in which they appeared historically. Although we'll be covering more modern versions of them, the inspiration for the two theories we are covering today is ancient. This is because thinkers far back in the Western tradition have been thinking about why we behave in the way we do, why we build big cities, build empires; why we sometimes work together and at other times slaughter each other. We know that Western thinkers had theories about this because the works of some very important thinkers have survived to tell us about them. One such thinker is Plato (circa 425 to 348 BCE).

Bust of Plato.

Plato wrote primarily in dialogue form. Typically his dialogues would take the form of an at least partly fictionalized dialogue between some ancient thinker and Plato's very famous teacher, Socrates. In Plato's masterwork Republic, the character of Socrates attempts to define justice while responding to the various objections of other characters, which expressed views that were likely held by some thinkers of Plato's time. In effect, this might be Plato's way of defending his view against competing views of the time, although there is some debate about this.

In the dialogue, after some initial debate, the characters decide to build a hypothetical city, a city of words, so that during the building process they can study where and when justice comes into play. At first they build a small, healthy city. Everyone played their own role which served others. There was a housebuilder, a farmer, a leather worker, and a weaver so that they could have all the essentials. At this point, a character named Glaucon objected to the project. He argued that this is not a real city; it's a "city of pigs", a city where people would be satisfied with the bare minimum. A real city, with real people, would want luxuries and entertainment. So at Glaucon's behest, the characters expanded the city to give its inhabitants the luxuries they likely wanted. Soon after, the characters realized the city would have to make war on its neighbors; they would need an army and they would need rulers.

Glaucon's objection is rooted in a specific idea about human nature. This thread was picked up on millennia later, during the Enlightenment, by thinkers like Bernard Mandeville and Thomas Hobbes. It's this notion that all human actions are rooted in self-interest. That is, some thinkers have put forward the thesis that you can explain all human action through self-interest: our behaviors, our institutions, our moral codes, everything. Although it goes by many names, we will refer to this view as psychological egoism, and it takes us to the first ethical theory we will cover.

Ethical egoism

So our first theory, then, will be ethical egoism: an action is right if, and only if, it is in the best interest of the agent performing the action. Here is a simple argument for the view.

- If the only way humans are able to behave is out of self-interest, then that should be our moral standard.

- All human actions are done purely out of self-interest, even when we think we are behaving selflessly (psychological egoism).

- Therefore, our moral standard should be that all humans should behave purely out of self-interest.

In a nutshell, this argument states that if all we can do is behave in a self-interested way, that’s all we should do. Premise 1 seems reasonable enough. A thinker that we will come to know better eventually, Immanuel Kant, argued that if we should do something, then that implies that we can do it. Although Kant did not believe in psychological egoism, we can accept his dictum that we should be able to do what we are required to do. This implies that if we can't help but to act in a self-interested way, then that's the only rational standard we should be held against. In short, because psychological egoism is true, then ethical egoism is true as well.

Proponents of ethical egoism argue that psychological egoism can explain all human actions. It does seem to account for many of our behaviors. For one, sometimes people are selfish. Sometimes, however, people cooperate and behave in seemingly altruistic ways—that is, for the benefit of others. Egoists claim their view can also account for this sort of behavior because it’s possible people behave this way only to: get the benefits of working cooperatively, or enjoy moral praise (from themselves and others), or just avoid feeling guilt. Let's be honest, some of you don't lie or steal simply because you couldn't bare the guilt.

But does ethical egoism explain all human behaviors and institutions? Can self-interest alone really explain the full range of diverse actions we take? Can it explain the behavior of Mother Teresa? Well, egoists might argue that even Mother Teresa acted in a self-interested way. After all, if her faith was well-placed, she did get a reward for her life's work: eternal bliss in heaven—Pascal's infinite expected utility.

The Purge

Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679).

To transition to our second ethical theory (contractarianism), let's begin with a question. If you found yourself in a situation where there was a total breakdown of central authority (no cops, no government aid), as in movies like World War Z or The Purge, what would you do to stay alive? Would you lie and steal? Would you kill?1 If you think you would, then you might agree with Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679). Although it is difficult to disambiguate his ethical theory from his political philosophy, it's safe to say that Hobbes had a dark ethical theory. Hobbes, assuming that psychological egoism is true, agrees with Glaucon that all prosocial behavior is merely a state of affairs we submit to purely out of self-interest. Morality is a convenient fiction. In short, we submit to an authority and give it a monopoly on violence because the alternative, the state of nature where everyone is at war with each other, is substantially worse. Justice and morality are mere social contracts; if society collapses, you can feel free to ignore these contracts. This looks real bad for moral realism...

“Hereby it is manifest that during the time men live without a common power to keep them all in awe, they are in that condition which is called war; and such a war as is of every man against every man... In such condition there is no place for industry, because the fruit thereof is uncertain: and consequently no culture of the earth; no navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by sea; no commodious building; no instruments of moving and removing such things as require much force; no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short" (Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, i. xiii. 9)

We'll learn more about Hobbes in the video below.

Decoding Hobbes

The State of Nature

LA riots, 1992.

Is Hobbes' right? Certainly we have seen unthinkable acts of violence and theft when there is a breakdown in central authority. From the LA Riots in 1992 to involuntary euthanasia during the Hurricane Katrina disaster, and even more recently during the looting after the George Floyd protests.2 We will give a more careful assessment of SCT in the next lesson, but for now I want you to think about how the breakdown of central authority is at least correlated with some instances of immorality and blatant disregard for the law. But Hobbes' theory mostly rests on one biological trait: psychological egoism. Is it truly the case that all human actions are driven by self-interest?

Skepticism about libertarian free will, which is the only type of free will which will be considered moving forward, leads to skepticism about moral responsibility. However, it does appear that we justifiably hold people morally responsible for the morally wrong actions that they engage in. This suggests that perhaps a defense of free will can come from a defense of something like moral realism.

This lesson, however, introduces us to two anti-realist (or non-objectivist) ethical theories: ethical egoism and Hobbes' social contract theory.

Both theories ultimately depend on a view about human nature: that all human actions are rooted in self-interest. This view is called psychological egoism. The truth of psychological egoism, though, is ultimately an empirical question—one that scientists, not philosophers, will have to address.

FYI

Suggested Reading: Plato, The Republic, Book II

-

Note: Read from 357a to 367e.

TL;DR: The School of Life, POLITICAL THEORY: Thomas Hobbes

Supplemental Material—

- Video: Peter Millican, Introduction to Thomas Hobbes

Advanced Material—

-

Reading: Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Entry on Egoism, Sections 1 & 2

-

Reading: Thomas Hobbes, On the Social Contract

-

Reading: Plato, The Republic, Book IX

-

Book: James Coleman, Foundations of Social Theory

-

Note: This is a more modern treatment of what is now dubbed “rational choice theory.”

-

Footnotes

1. I may as well tell you that I think all the Purge movies are awful and have led to the confusion among young people about what the philosophical position of anarchism really stands for.

2. I recommend the documentary LA 92 on the social injustice and unrest leading up to the LA riots.