Aquinas

and the Razor

My name is Legion: for we are many.

~Mark 5:9

Dilemma #3: Does God exist?

The uncomfortable question that titles this subsection leads to the even more uncomfortable analysis of the arguments for God's existence that have been given throughout history. Equally discomforting is what I'm about to say: there's about a thousand years—the first thousand years, roughly speaking—of Christian history that will offer very little of value. Of course, my guess is that you will not consider this blanket statement to be in good judgment. And so, I'll happily explain my reasoning in this lesson and the next.

First, however, I must make some preliminary comments. Recall that we are endeavoring to answer this question because we are attempting to find support for the Cartesian rationalist/foundationalist project. Descartes, it is clear from his Meditations, considered himself a devout Catholic. Descartes, moreover, believed that God, through His goodness, could be the solution to the problem of skepticism. And so, to keep the narrative flow of the course, we will look exclusively for proof of God as envisioned by the Catholic tradition. I hope this omission does not offend any students taking this course who align with Protestantism, the Church of Latter-day Saints, Islam, Hinduism, Wiccanism, etc.

Second, the approach will be, by and large, historical. This is, to repeat myself, first and foremost an intellectual history. As such, I want us to focus on arguments and ideas that would've been available to people in the early modern period in Europe. We can, at times, look at other arguments for and against God's existence that are more contemporary. But in the final analysis, these will have to be bracketed and put aside when assessing Cartesian foundationalism (although we can certainly discuss the meaning of contemporary arguments for and against God's existence for our own lives).

Third, I will make my very best attempt to give both sides of this debate. There are four lessons on the philosophy of religion in total. The first and the third will advance arguments for God's existence (and critique them); the second and fourth lessons will be given from the perspective of an atheist (and discuss some limitations). This bipolar approach might be jarring at first, but I think it is a useful method nonetheless.

Fourth, given that we are exclusively be discussing Catholicism, it should be said at the outset that when I use terms like "believers", "the faithful", and other allusions to adherents of a particular religion, I mean adherents to Catholicism. Again, this is for the sake of the narrative and has nothing to do with excluding non-Catholics.

Lastly, these arguments are very much only the "greatest hits" of philosophy of religion, something that is inevitable in an introductory course. A thorough review of the arguments for and against God's existence takes much longer than 4 brief lessons. The interested student can enroll in a philosophy of religion course. The references given in these lessons might also make valuable reading material.

The Closing of the Western Mind

I made a contentious claim in the last subsection: that about a thousand year span of Christian history made no worthwhile arguments for God's existence. I defend that claim now.

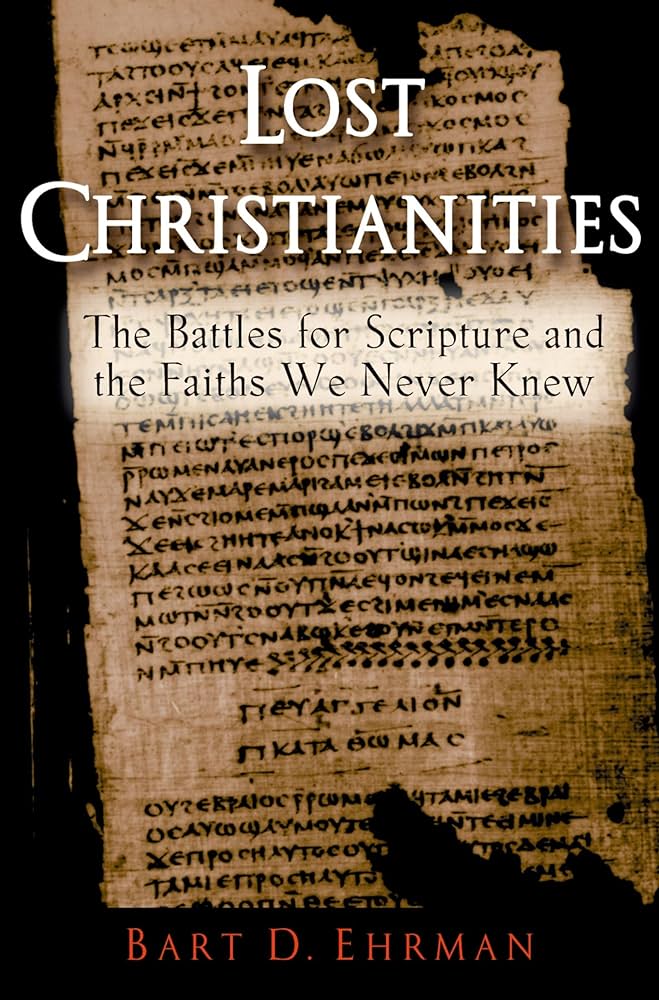

Although I cannot peer into the minds of people, my guess is that most believers think that Christian doctrine is and has always been clearly articulated, with no major dissension. Nothing could be further from the truth. The history of the early Church was littered with heated theological disputes, some of which became lethal. For example, in Lost Christianities, Bart Ehrman details the various competing interpretations of what Christianity meant. One worthy of mention is the adherents of a view known as gnosticism. This Christian sect believed that spiritual knowledge trumped any authority the Church might have, which you can imagine did not sit well with early church leaders. There was also, according to this sect, two gods: a good one and an evil one.

Another dispute that shook the early Church was over what eventually would be called the Arian heresy: the view that Jesus, although divine, was created by God and was subordinate to God. What would eventually become the orthodox (or official) position was that Jesus, or God the Son, has always been co-equal with God the Father. There are, however, various Bible passages that support the Arian interpretation over the orthodox interpretation (e.g., Mark 10:18, Matthew 26:39, John 17:3, Proverbs 8:22; see Freeman 2007: 163-177 for a full discussion). The existence of these passages explains why it was so difficult to stamp out the Arian heresy, which persisted well into the 4th century.

There was even dissent between church leaders, such as the rift between St. Paul and St. Peter. Paul seems to have been difficult to work with and he distanced himself from those who had actually known Jesus (such as Peter). Paul's insecurity over his questionable authority caused him to stress the supernatural aspects of Jesus, such as his resurrection, as well as how he received a revelation, the implication being that knowing Jesus personally is not the only way to receive the good news (see Freeman 2007, chapter 9).

And as if all this wasn't bad enough, there was even discord in a single person's interpretation of events. To take the example of Paul again, it turns out Paul was inconsistent in his teachings. Initially, he said that faith alone will save you. But this was because he believed that the second coming was imminent, and there was no time to change one’s behavior. Only later, once the second coming failed to materialize, did he stress the need for charity (ibid.).

Constantine, the Great.

Then came Emperor Constantine. Realizing that persecuting Christians wasn’t working, he decided to show them tolerance in the Edict of Milan, co-adopted with the Eastern emperor Licinius. (Note that by this point, the Roman Empire had multiple emperors at once to help rule the vast empire.) As a way to gain the favor of Christian communities that had been persecuted, Constantine gave exemptions from the heavy burdens of holding civic office and taxation to the clergy. However, he was surprised by the amount of communities that called themselves "Christians" as well as by their conflicts with each other. Given that he had lavished gifts on the Christian clergy, there was an urgency for clarifying what “Christian” really meant. Constantine ended up selecting those more pragmatic communities of "Christians" to maintain their civic gifts and withdrew his patronage from the others. In doing so, he began to shape what would become the Catholic Church.

However, this did not end the disputes, which seemed to somewhat irritate Constantine. He thus convened the Council of Nicaea in 325 CE to try to establish what orthodox Christianity really was. The factions, however, did not come to an agreement, and Constantine had to settle theological matters by imperial decree. In other words, the non-Christian Roman emperor simply stipulated what the right view was. This happened time and time again in the history of the Church, with different emperors settling different theological disputes by decree. Not only does this seem less-than-divinely inspired, but it also imbued, at least the Western half of the empire, with a persistent and pervasive authoritarianism. Authority seemed like the way to solve problems. Moreover, once Christians had the backing of the state, they turned to the persecution of pagans. This persecution was literal, and it included destruction of pagan temples, harassment, and murder (see Nixey 2018).

“’Mystery, magic, and authority’ are particularly relevant words in attempting to define Christianity as it had developed by the end of the fourth century. The century had been characterized by destructive conflicts over doctrine in which personal animosities had often prevailed over reasoned debate. Within Christian tradition, of course, the debate has been seen in terms of a ‘truth’ (finally consolidated in the Nicene Creed in the version of 381) assailed by a host of heresies that had to be defeated. Epiphanius, the intensely orthodox bishop of Salamis in the late fourth century, was able to list no less than eighty heresies extending back over history (he was assured his total was correct when he discovered exactly the same number of concubines in the Song of Songs!), and Augustine in his old age came up with eighty-three. The heretics, said their opponents, were demons in disguise who ‘employed sophistry and insolence’… From a modern perspective, however, it would appear that the real problem was not that evil men or demons were trying to subvert doctrine but that the diversity of sources for Christian doctrine—the scriptures, 'tradition', the writings of the Church Fathers, the decrees of councils and synods—and the pervasive influence of Greek philosophy made any kind of coherent ‘truth’ difficult to sustain... Both church and state wanted secure definitions of orthodoxy, but there were no agreed axioms or first principles that could be used as foundations for the debate... The resulting tension explains why the emperors, concerned with maintaining good order in times of stress, would eventually be forced to intervene to declare one or other position in the debate ‘orthodox’ and its rivals ‘heretical’” (Freeman 2007: 308-309).

Rediscovery

The preceding section showed that the early Catholic Church, rather than using reasoned debate and rational argumentation, relied on authority and the power of the state to establish Christian doctrine. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE, the region fell into its so-called dark age.1 Even prior to this, however, the nomadic tribes of the northern Arabian peninsula were progressively being unified into a meta-ethnicity (a coherent group composed of several ethnicities), perhaps surprisingly, by a shared language (particularly its high form, which was used for poetry). And then, in 570 CE, a man named Muhammad was born. After receiving his revelations, the unification of the Arab people was expedited, this time by religion (see Mackintosh-Smith 2019).

Early Muslim conquests.

The early Muslim conquests, 622-750, were lightning fast. In a historical blink of an eye, there was a new regional power. To show just how formidable the Muslim armies were, consider the Sassanid Persian Empire. The Sassanids had been at war with the Eastern Roman Empire (also known as the Byzantine Empire) for decades without one side truly defeating the other. Approaching the middle of the 7th century, though, the Sassanids began their military encounters with the Arab armies. The Sassanids, used to battle with the Byzantines, had a powerful but slow heavy cavalry. The Arabs, on the other hand, were light and quick-moving, and, through the combined use of camels and horses, were able to overwhelm the Persians. Not even war elephants could stop the Arabs, since some Arabs served as mercenaries during the Byzantine-Persian conflicts and knew how to deal with them. Eventually, compounded by bouts of plague and internal problems, the Sassanid Empire finally fell in 651.

The new Muslim Caliphates quickly became hungry for the intellectual insights of its conquered peoples and beyond. Historian of mathematics Jeremy Gray explains:

"When the Islamic empire was created, it spread over so vast an area so quickly that there was an urgent need for administrators who could hold the new domains together. Within ten years of Muhammad's death in AD 632 the conquest of Iran was complete and Islam stood at the borders of India. Syria and Iraq to the North were already conquered, and to the West Islamic armies had crossed through Egypt to reach the whole of North Africa. Since the Islamic religion prescribed five prayers a day, at times defined astronomically, and moreover that one pray facing the direction of Mecca, further significant mathematical problems were posed for the faithful... So it is not surprising that Islamic rulers soon gave energetic support to the study of mathematics. Caliph al-Mamun, who reigned in Baghdad from AD 813 to AD 833, established the House of Wisdom, where ancient texts were collected and translated. Books were hunted far and wide, and gifted translators like Thabit ibn Qurra (836-901) were found and brought to work in Baghdad... So diligent were the Arabs in those enlightened times that we often know of Greek works only because an Arabic translation survives" (Gray 2003: 41).

A madrasa, or place of study.

Although the Muslim conquests are fascinating in their own right, they are relevant in our story because of what happens next. In 1095, Pope Urban II calls for the First Crusade. He instigated this Crusade by exaggerating the threat of Turkish aggression at Constantinople, as well as poor treatment of Christians by Muslims (e.g., during pilgrimages). Most importantly, he demonized Muslims. And so, the Crusades began with the goal of taking back the Holy Land (see Asbridge 2011). Depending on what you count as a "Crusade", the story ends at different times. For our purposes, the Crusades ended when Acre falls to the Mamluk Sultanate in 1291.

How is this relevant to our story? It was during these centuries of prolonged contact with Islamic peoples that Europeans began rediscovering and reacquiring many ancient texts in mathematics, philosophy, and more. We will see this rebirth take place as we study two arguments for God's existence. The first will be by St. Anselm, written before the Crusades; the second will be by St. Thomas Aquinas, written towards the end of the Crusades.

Important Concepts

Some comments on metaphysics

I had previously said that you can just think of metaphysical questions as being of the sort "What is ______?" The reason for this short-hand is that metaphysics, much like philosophy itself, has been different things at different times. In classical Greece, metaphysics was delving into the ultimate nature of reality and it included some theories about cosmogenesis. By the 20th century, cosmogenesis was the purview of physics, and some philosophers, notably the members of the Vienna Circle, attacked metaphysics and demanded that the branch of philosophy be shutdown. Today, given the state of theoretical physics, some philosophers (who are also trained in physics and/or mathematics) dive into the metaphysics of reality once more (see Omnès 2002). In short, defining metaphysics is tough, since it somewhat depends on the historical context.

Decoding Anselm

Decoding Aquinas

Ockham

Telling the story of Thomas Aquinas and his Five Ways is not complete without telling the story of William of Ockham. Ockham, as I'll refer to him, was a Franciscan friar who was born around 1287 and died in 1347. He is best known for endorsing nominalism, a view we'll cover in Unit III. He is relevant here due to his use of a methodological principle that bears his name: Ockham's razor. Ockham's razor, a.k.a. the principle of parsimony, is the principle that states that given competing theories/explanations, if there is equal explanatory power (i.e., if the theories explain the phenomenon in question equally well), one should select the one with the fewest assumptions. Expressed another way, it's the principle that states that, all else being equal, the simplest explanation is the most likely to be correct. Put a third way, don't assume things that don't add explanatory power to your theory, i.e., don't assume things that have no value in helping you explain a phenomena. In short, when explaining a phenomena, don't assume more than you have to.

Ockham's razor is applicable in many different fields. In computer science, although one starts off just trying to get the code to do what it's supposed to do, eventually, a good programming practice to develop is to make your code more elegant and simple so that it is easier to read by other developers (see Andy Hunt and Dave Thomas' The Pragmatic Programmer). In the social sciences, it is a feature of good theories to not assume more than what is necessary. If you can explain, for example, the Fall of the Western Roman Empire through disease, naturally-occurring climate change, social unrest, and external threats, then it's no good to also add in there some fifth factor that doesn't add any explanatory value.

One domain where I wish people would use Ockham's razor is in the realm of conspiracy theories. Often times, when someone espouses a conspiracy theory, they must assume many more things than the non-conspiracy theorist, such as secret societies, space-alien races, hitherto unknown chemicals and weapons, etc. Moreover, these extra assumptions actually have zero explanatory power. If you are attempting to explain some event via, for example, a secret society, then you have effectively explained nothing because the society is SECRET. That means you don't know their dark plan, or their sinister methods, etc. It's the equivalent of attempting to explain something you don't understand by using some other thing you don't understand as the explanation. Utter nonsense.

The full story of Ockham can only be told in a class on the Middle Ages, but suffice it to say here that Ockham's gave commentaries on theological matters much like that of Aquinas' natural theology. Mind you, Ockham was a believer, but he also didn't think the arguments of his day proved God's existence. Ockham was not alone. Duns Scotus, another Franciscan friar who was about two decades the elder of Ockham, found some difficulties in reconciling God's freedom with any reasoned argumentation or proof of God's existence.

“Duns Scotus (d. 1308) gave open expression to the rejection of reason from questions of faith. God, he held, was so free and his ways so unknowable they could not be assessed by human means. Accordingly there could be no place for analogy or causality in discussing him; he was beyond all calculation. Duns, in the great emphasis he placed on God's freedom, put theology outside the reach of reason” (Leff 1956: 32).

What Scotus is saying is that God is so free and so powerful that he can just change reason itself. The laws of logic can be bent by God if God chose it. So any attempted proof of God, through reason argumentation, would fail, since it would assume something that God can destroy at will: the laws of logic.

"For the skeptics [of scholasticism], God, by his absolute power, was so free that nothing was beyond the limits of possibility: he could make black white and true false, if he so chose: mercy, goodness, and justice could mean whatever he willed them to mean. Thus not only did God’s absolute power destroy all [objective] value and certainty in this world, but his own nature disintegrated [in terms of the human capacity for understanding God through rational reflection]; the traditional attributes of goodness, mercy and wisdom, all melted down before the blaze of his omnipotence. He became synonymous with uncertainty, no longer the measure of all things” (Leff 1956: 34; interpolations are mine).

William of Ockham.

In other words, for Ockham and others, since God is all-powerful, He could change anything at anytime, including our methods of human reasoning and logic itself. Put another way, human reason and logic are insufficient to understand a being this powerful. Since all arguments are grounded by human reason and logic, all arguments are insufficient to establish the existence of God, let alone an understanding of Him.

Again, Ockham (and Scotus) were believers. Ockham's view on his faith is called fideism. Fideism is the view that belief in God is a matter of faith alone. Any attempt to prove God’s existence is futile.

On account of his teachings, Ockham and others were called to Avignon, France, in 1324, to respond to accusations of heresy. After some time in Avignon, during which a theological commission was assessing Ockham's commentaries on theological matters, Ockham and other leading Franciscans fled Avignon, fearing for their lives. He lived the rest of his life in exile.

Ockham, however, plays an important role in the intellectual history of the Middle Ages. Indeed, Ockham serves as a breakpoint. Up to that point, the goal of philosophy in the Middle Ages was to affirm and reinforce the predominant theological views of the time. In other words, philosophy was just for defending existing religious doctrine. But Ockham saw the roles that philosophy and theology played as being distinct. In particular, philosophy could not really function to defend belief in a supernatural deity; it had, instead, its own separate function of exploring and defending philosophical positions (on politics, metaphysics, art, etc.). Historian of science W. C. Dampier writes of the intellectual milestone that is the work of William of Ockham:

“[T]he work of Occam marked the end of the mediaeval dominance of Scholasticism. Thenceforward philosophy was more able to press home its enquiries free from the obligation to reach conclusions foreordained by theology... [T]he ground was prepared for the Renaissance, with humanism, art, practical discovery, and the beginnings of natural science, as its characteristic glories” (Dampier 1961: 94-5).

On account of Descartes' needing God to rescue us from skepticism, we are seeking an answer to the question of God's existence. Our focus will be on Catholicism.

During the early part of the Middle Ages, reasoned argumentation was not at its best in the West. It was primarily through prolonged contact with Muslim caliphates that the West rediscovered the Greek-style of argumentation.

Thomas Aquinas' work marks the height of the attempted combination of reason and faith. He essentially argues for God's existence using Aristotelian reasoning, albeit a Christianized version.

Approaches to theology like that of Aquinas, however, had some critics. We noted the work of William of Ockham.

Ockham argued that human reason and logic are insufficient to understand God since God (through his power) can simply change the laws of logic.

Per historian of science W. C. Dampier, Ockham's work marks the end of Scholasticism's dominance in the West and paved the way for the Renaissance and more.

FYI

Suggested Reading: Gordon Leff, The Fourteenth Century and the Decline of Scholasticism

TL;DR: Sky Scholar, What is Occam's Razor? (Law of Parsimony!)

- Note: The Sky Scholar (Dr. Robitaille) is very cheesy. I love it.

Supplementary Material—

-

Reading: Theodore Gracyk, Aquinas and the Five Ways

Advanced Material—

-

Reading: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Entry on Ockham

-

Note: Read Sections 1, 2, and 6

-

-

Reading: William Cecil Dampier, Chapter 2 of A History of Science and its Relations with Philosophy of Religion

-

Reading: Frank Thilly, Chapter 30-33 of A History of Philosophy

Footnotes

1. Interpreting what "dark age" means requires some clarification. In chapter 6 of his Against the Grain, James C Scott beckons us to reconsider the use of the phrase “dark age.” Dark for whom? Is it merely decentralization? Is it merely that we can’t study it as well? Is it a real drop in health and life expectancy for the people? In many cases, it might've been a simple reversion to a simpler, more local way of life, without an imperial ruler unifying disparate peoples. Nonetheless, I will use this phrase here for rhetorical elegance.