Cogito

If you would be a real seeker after truth, it is necessary that at least once in your life you doubt, as far as possible, all things.

~René Descartes

Aristotle's dictum

Up to this point, we've been using the analogy between worldviews and jigsaws or between worldviews and webs of beliefs (which was philosopher W.V.O. Quine's preferred metaphor). Analogies, unfortunately, have their limitations. As it turns out, there are aspects of the downfall of worldviews that are decidedly not like a jigsaw puzzle (or a spider's web, for that matter). For example, once a worldview is torn apart, it is not uncommon for thinkers to parse through the detritus, find a pearl, and incorporate it into their new worldview. This would be as if someone, after breaking apart the completed jigsaw puzzle that decorated their living room coffee table, were to then take a prized puzzle piece from that set and use it in a different jigsaw. Surely that doesn't make much sense. Nonetheless, this is how the partitioning of worldviews goes: not all beliefs are tossed. There are always some pearls of wisdom that can be updated, or otherwise adapted to the new normal.

First, some context. If I painted too rosy a picture of the end of the Tudor period in the last lesson, you will forgive me—I hope. My perception might have been altered by my knowledge of what happened next. As if we needed a reminder that, in the past, societal advancements were often accompanied by backtracking, both nature and established institutions pushed back against intellectual progress and stability—with a vengeance. In 1600, for example, philosopher and (ex-)Catholic priest Giordano Bruno was burned at the stake for his heretical beliefs in an infinite universe and the existence of other solar systems. Even more tragic, if only because of the sheer magnitude of the numbers involved, was the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648), which claimed the lives of 1 out of 5 members of the German population. This began as a war between Protestant and Catholic states. However, fueled by the entry of the great powers, the conflict wrought devastation to huge swathes of territory, caused the death of about 8 million people, and basically bankrupted most of the belligerent powers.

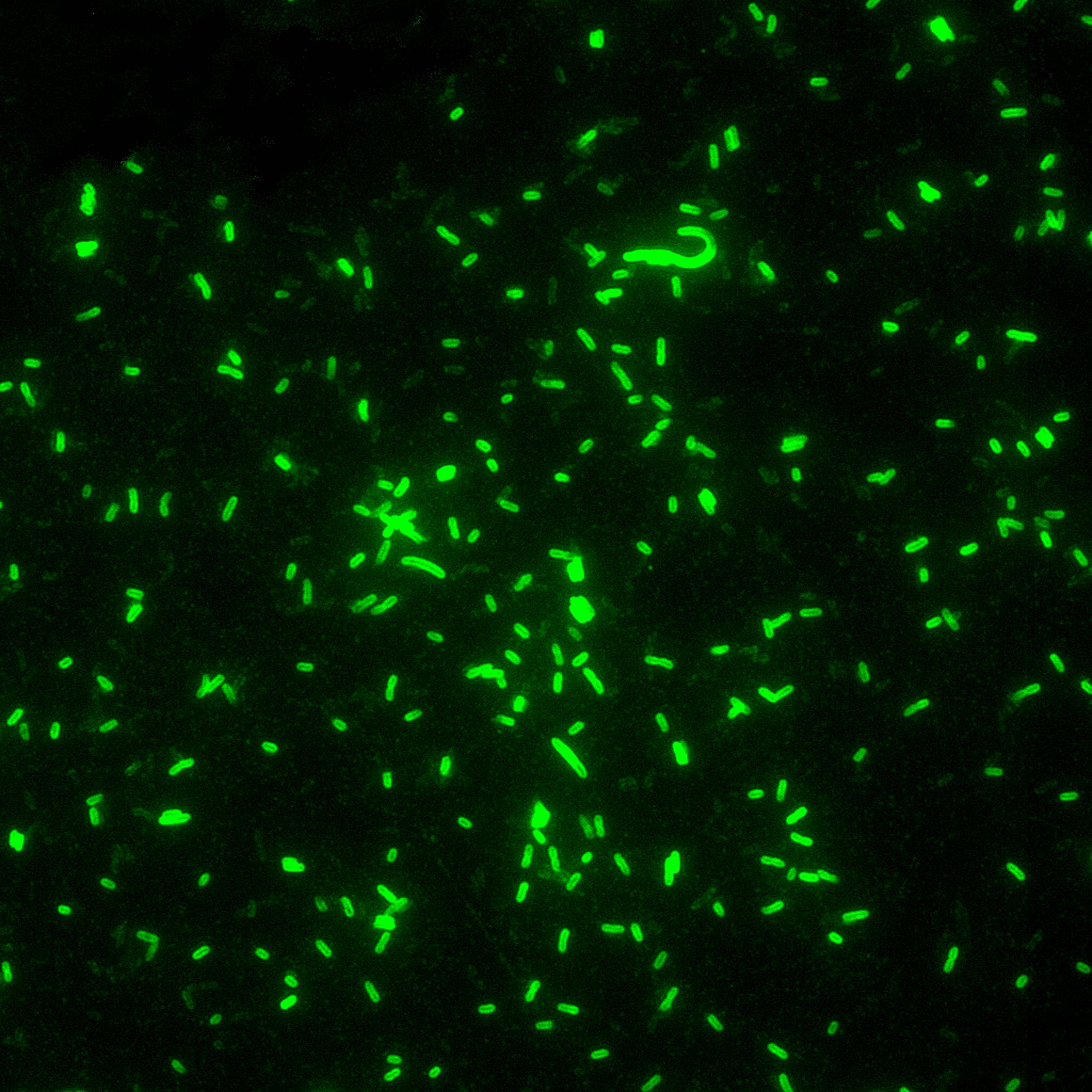

Yersinia pestis, the bacteria

which causes plague.

As if human-made suffering isn't unhappy enough, Mother Nature often only compounds the agony. In 1601, due to a volcanic winter caused by an eruption in Peru, Russia went through a famine that lasted two years and killed about one third of the population. There were also intermittent resurgences of bubonic plague in Europe, northern Africa, and Asia throughout the 17th century. I, of course, don't have to tell you that a tiny virus 125 nanometers in size can cause major cultural, political, and economic disruptions.

But thinkers of the time did not know yet about germ theory, let alone climate science. The former would have to wait until the work of Louis Pasteur in the 1860s. Intellectuals instead focused on a domain that they felt they might be able to affect: our religious convictions. Thinkers like René Descartes (the subject of this lesson whose name is pronounced "day-cart") and John Locke (the subject of the next lesson) noticed that religious fanatics could reason just as well as logicians. The problem, they thought, was that they began with religious assumptions that they took to be universal truth. From these dubious starting points these fanatics were able to justify the killing of heretics, the torture of witches, and their religious wars. In other words, these thinkers, like many others of their age, wanted to ensure that people reasoned well, that people would filter their beliefs and discard those that didn't stand up to scrutiny. A worthy goal, indeed.

How should we reason? Descartes believed that our premises must be more certain than our conclusions. In other words, we must move from propositions that we have more confidence in to those that we have less confidence in (at least initially, before argumentation). In fact, however, Aristotle had made this point in his Posterior Analytics almost two thousand years before (I.2.72.a30-34). As such, we will call this principle, that we should move from propositions that we have more confidence in to those that we have less confidence in, Aristotle's dictum. Remember: never throw out the baby with the bathwater.

Reasoning Cartesian style

Descartes gives the metaphor of a house. We must build the house on a strong foundation, otherwise it collapses. Similarly, we must move from certain (or near certain) premises on towards our conclusion. Aristotle, by the way, speaks in a similar language. Aristotle talks about how our premises are the “causes” of our conclusions, but he’s talking about sustaining causes, the supports that keep our conclusions from crashing down.

Cartesian coordinates.

Descartes uses this epistemic principle to argue against circular reasoning. For example, recall the example we gave for the informal fallacy of begging the question. Say someone believes that (A) God exists because (B) it says so in the Bible, a book which speaks only truth; and they also believe that (B) the Bible is true because (A) it comes from God (that exists). Clearly this person can’t find both A and B more convincing than the other. This is clearly circular reasoning (for a discussion, see Shenefelt and White 298: n11). The trouble with religious fanatics, Descartes reasoned, is that their premises are not known to begin with. And from these false beliefs they build an even more dubious superstructure. Realizing this, Descartes decided to use the method of doubt (or hyperbolic doubt), disabusing himself of anything he didn’t know with absolute certainty. Stay tuned.

Newton claimed that he stood on the shoulders of giants, but most people don’t really know which giants he spoke of. I’ll go ahead and tell you, at least with regards to Newton’s first law of motion. Galileo (1564-1642) came close to getting it right, but it was Descartes (1596-1650) who first to clearly state the principle. Finally, Newton (1642-1727), borrowing heavily from Descartes’ formulation, incorporated it into his own greater mechanical view of the universe (see DeWitt 2018: 100).

This goes to show that Descartes was much more than a philosopher; he was also a gifted mathematician and scientist. One of his most famous insights was the bridging of algebra and geometry (as in Cartesian coordinates, pictured here). I might add, however, that Descartes doesn’t get sole credit for coordinate geometry. French lawyer and mathematician Pierre de Fermat arrived at the same broad ideas independently and concurrently.

Important Concepts

Stragglers

As we saw in the last section, not all of the ideas from the Aristotelian worldview were discarded. For one, Aristotle's dictum was preserved and used by Descartes in an attempt to tamper the religious fanaticism of the time. But there were other ideas that Descartes felt should be preserved. One of those was the hope for deductive certainty about the world.

Recall that by this point in history there was an alternative conception of knowledge: Bacon's pragmatist approach. Although we've already looked at problems with this view, I'd like to drive these a little further now. Pragmatism, as we've seen, melds well with a coherence theory of justification. But coherentism leaves us with many unanswered questions. For example, is a statement true because it coheres with an individual’s web of beliefs? This, by the way, is sometimes referred to as alethic relativism. It seems like most individuals aren't reliable enough to be counted to have a well-supported coherent set of beliefs. Should we instead say that a statement is true only if it coheres with a whole group’s web of beliefs? If that's the case, how do we decide who’s a member of the group? Do they have to be experts? How do we decide who’s an expert?

Perhaps the most worrisome implication of pragmatism is the possibility that everything we currently know to be true could be overturned by empirical developments. In other words, it could very well be the case, according to the logic of pragmatism, that the worldview that we hold in the 21st century could be completely overthrown in the decades and centuries to come. Moreover, that worldview might itself also eventually be overthrown. It is possible that everything we think we know is actually false. This is called pessimistic meta-induction, and it's very worrisome for some people.

Descartes, it seems, was definitely not comfortable with this notion. The alternative appeared to be JTB theory + the correspondence theory of truth + realism about science. Now, it should be said that Descartes didn't use any of these labels. Instead, we are labeling Descartes' views after the fact, but it's worth it because it will help us understand a very important point. Stay tuned.

This alternative package of views (JTB theory + the correspondence theory of truth + realism about science) isn't without its problems. Both the correspondence theory of truth and realism about science have their objections. But let's just focus on the JTB theory. After all, we've already looked at a problem for this view: the regress argument. Until we solve the regress, we really can't move forward with this constellation of views. We know this, and Descartes knew it as well.

And so Descartes sought to establish solid foundations for science and common sense. He thought to himself that there must be some things we know with absolute certainty, things that are self-evident, things that cannot be denied. Since these beliefs cannot be doubted or questioned, then these are regress-stopping beliefs. In other words, these are foundational beliefs, and upon these foundational beliefs we can build the rest of our beliefs. That's how Descartes planned on stopping the regress: by starting with beliefs that literally could not be questioned.

How do you discover foundational beliefs? For this goal, Descartes employs his Method of Doubt, also referred to as hyperbolic doubt. In a nutshell, Descartes would discard any beliefs that he did not know with absolute certainty. He would take as long as he needed to because, in the end, whatever was left over was known with 100% confidence. In other words, at the end of that process, he should have his foundational beliefs. On those beliefs, he would explain the rest of the world.

Descartes' goals

Descartes' story is complicated and interesting, and we cannot do justice to his life here. One tantalizing detail that just can't be left out, though, is that he served as a mercenary for the army of the Protestant Prince Maurice against the Catholic parts of the Netherlands during the early stages of the Thirty Years' War. It was there that he studied military engineering formally. Although we do not know his actual course of study, he very likely studied the trajectories of cannonballs and the use of strong fortifications to aid in defense and attack. Can you see any analogies to his philosophical project?

In any case, the interested student can consult a biography of Descartes for more details. Here, I'd like to focus instead on what was happening to Descartes' contemporaries and how that might've influenced Descartes' thinking. Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) was an advocate of the heliocentric model. He was also thirty-five years the elder of Descartes and a very public figure. Even before his astronomical observations, Galileo had invented a new type of compass to be used in the military. This compass, developed in the mid- to late-1590s, helped gunners calculate the position of their cannon and the quantity of gun powder to be used. When the telescope was invented in 1608, Galileo set to observing the skies and made many important observations that would contribute to the downfall of the Aristotelian worldview. To add to his star power, Galileo became the chief mathematician and philosopher for the Medicean court.1 The Medicis were apparently flattered that Galileo named a group of four stars the Medicean stars. All this to say that if something happened to Galileo, intellectuals would notice.

In effect, something did happen to Galileo, although he certainly played a hand in this. Galileo, a fierce advocate of heliocentirsm, published his Dialogue Concerning Two Chief World Systems in 1632. In it, he insulted the powers that be (the Roman Catholic Church) by putting the position of the Church (geocentrism) in the mouth of the character called "the fool". This, of course, did not sit well with the pope. It should be added that at this point the Church was reeling from its conflict with the Protestants, and so the Church was a little touchy about challenges to its authority. And so, in 1633, the Inquisition condemns Galileo to house arrest, although it could've been worse. Already in his 60s, Galileo died a few years later.2

Before leaving Galileo, it should be said that, although he was immensely important in the history of science for many reasons, one stands out. He was one of the first modern thinkers to clearly state that the laws of nature are mathematical. Morris Kline writes:

“Whereas the Aristotelians had talked in terms of qualities such as earthiness, fluidity, rigidity, essences, natural places, natural and violent motion, potentiality, actuality, and purpose, Galileo not only introduced an entirely new set of concepts but chose concepts which were measurable so that their measures could be related by formulas. Some of his concepts, such as distance, time, speed, acceleration, force, mass, and weight, are, of course, familiar to us and so the choice does not surprise us. But to Galileo’s contemporaries these choices and in particular their adoption as fundamental concepts, were startling” (Kline 1967: 289).

How is this related to Descartes? We must recall that at this time period religion gave meaning to every sphere of life. As it turns out, we don't have to travel far to see religious inspiration. The very same scientists who played a role in the downfall of Aristotelianism were motivated by religious fervor. Copernicus was motivated by neo-Platonism, a sort of Christian version of Plato's philosophy (DeWitt 2018: 121-123), and Kepler developed his system, which was actually right, through his attempts to "read the mind of God" (ibid., 131-136). Even Galileo was a devout Catholic; he just had a different interpretation of scripture than did Catholic authorities.3

Yuval Noah Harari reminds us that up until the dawn of humanism, religion gave meaning to every sphere of life.

“In medieval Europe, the chief formula for knowledge was: knowledge = scriptures × logic. If we want to know the answer to some important question, we should read scriptures and use our logic to understand the exact meaning of the text... In practice, that meant that scholars sought knowledge by spending years in schools and libraries reading more and more texts and sharpening their logic so they could understand the texts correctly” (Harari 2017: 237-8).

Religion gave meaning to art, music, science, war, and, if you recall, even death. The following contains graphic descriptions of executions which were practiced in Descartes' native France. Those who are sensitive can and should skip this video.

And so Descartes had to toe a fine line. He, obviously, wanted to continue to engage in scientific research, but he didn't want to end up like Galileo. He wanted to find a way to reconcile science and the Church. He needed to establish a foundation for science without alienating the faithful. But how? After a long gestation period, Descartes finally publishes his Meditations in 1641.

“Because he had a critical mind and because he lived at a time when the world outlook which had dominated Europe for a thousand years was being vigorously challenged, Descartes could not be satisfied with the tenets so forcibly and dogmatically pronounced by his teachers and other leaders. He felt all the more justified in his doubts when he realized that he was in one of the most celebrated schools of Europe and that he was not an inferior student. At the end of his course of study he concluded that all his education had advanced him only to the point of discovering man’s ignorance” (Kline 1967: 251).

Decoding foundationalism

Into the fray...

At this point, we have two different conceptions of knowledge competing with each other. Moreover, they are both a constellation of views. They're like little worldviews, not as all-encompassing as the Aristotelian worldview, but still a coherent system of beliefs nonetheless. They are:

- A Cartesian view: JTB theory + correspondence theory of truth + foundationalism + realism about science.

- A Baconian view: pragmatism + coherence theory of truth + instrumentalism about science.

Notice that I didn't call them "Descartes' view" and "Bacon's view". Just as with the Aristotelian worldview, this isn't exactly what they believed. These labels are simply a means for us to talk about these concepts, and they may or may not have matched perfectly how Descartes and Bacon actually thought. These different approaches to knowledge are certainly, however, in the spirit of each of these thinkers.

For rhetorical elegance, I won't call them the Cartesian view and a Baconian view. I'll use a shorter label. For the Cartesian view, I will use the label foundationalism. This is a little clumsy in that it is both the name of a theory about how to stop the regress as well as the name for the overall constellation of views. I think that's ok, though. The reason for this is that foundationalism (as a means to stop the regress) is what holds the constellation of views together. It's sort of the "band-aid" that fixes the regress problem and keeps the JTB theory, the correspondence theory of truth, and realism about science alive. For the Baconian view, things are a little simpler. It has a label. We will refer to it as positivism.4

When a worldview collapses, it is the central beliefs that tend to die off. However, not all beliefs associated with the worldview die off. For example, Aristotle's dictum, the view that you should move from premises that you are more certain of to conclusions that you are less certain of (at least initially), was still advocated as the Aristotelian worldview was collapsing and is still considered a good maxim for reasoning even today.

- Note: It might be added that a whole field that Aristotle started, the study of validity (a field known as logic), was also not discarded along with the Aristotelian view. This field had amazing leaps forward in the 19th century and is an integral part of computer architecture and computer science today. The interested student can take my symbolic logic course for more.

Descartes decided to attempt to rescue deductive certainty in science as the Aristotelian worldview was collapsing. In other words, he wanted to find a way to establish the foundations of science such that the truths of science are known with certainty.

Descartes was also looking for a way to reconcile science and faith, as well as a method for pacifying religious fanaticism.

Descartes' foundationalist project is not entirely without other motivations. Pragmatism carries with it the possibility that everything we think we know is actually false; this is called pessimistic meta-induction. Avoiding this would've been appealing to thinkers in the early modern period.

Using the method of doubt, Descartes arrived at his four foundational truths:

- He, at the moment he is thinking, must exist.

- Each phenomenon must have a cause.

- An effect cannot be greater than the cause.

- The mind has within it the ideas of perfection, space, time, and motion.

We now have two competing constellations of views: foundationalism and positivism.

FYI

Suggested Reading: René Descartes, Meditations on First Philosophy

-

Notes:

-

Read only Meditations I & II.

-

Here is an annotated reading of Descartes’ Meditations, courtesy of Dan Gaskill at California State University, Sacramento.

-

TL;DR: Crash Course, Cartesian Skepticism

Related Material—

-

Video: Nick Bostrom, The Simulation Argument

-

Netflix: The interested student should also watch "Hang the DJ" (Episode 4, Season 4) of the Netflix series Black Mirror.

Advanced Material—

-

Reading: The Correspondence between Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia & René Descartes

-

Reading: Michael Williams (2004), Scepticism and the Context of Philosophy

Footnotes

1. At this point in time, the term philosopher meant what we would today call a scientist (see DeWitt 2018: 143). We talked about this in Lesson 1.1 Introduction to Course.

2. It is my understanding that Galileo got some revenge, sort of.

3. The interested student can read Galileo's Letter to Castelli, where he most clearly articulates his views on the matter.

4. I might add that positivism should be understood as an umbrella term, since there are various "flavors" of positivism.