Endless Night (Pt. II)

The time has come for ethics to be removed temporarily from the hands of the philosophers and biologicized.

~E. O. Wilson

After Darwin...

About a decade after the publication of John Stuart Mill's Utilitarianism, Charles Robert Darwin published two books which sent shock waves across popular and intellectual circles. Darwin had already revolutionized science with his publication of On the origins of species in 1859, the founding document of evolutionary biology. But now he was taking things a step further, a very uncomfortable step for many of his readers. As Phillip Sloan reports in his Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Darwin, Darwin's own position on humans had remained unclear. But in the late 1860s, Darwin moved to explain human evolution in terms of his theory of natural selection. The result was the publication of Descent of man in 1871.

First, let's briefly summarize Darwin's theory of natural selection. The most—dare I say—gorgeous summary of the theory of natural selection that I've ever read comes from evolutionary biologist David Sloan Wilson:

“Darwin provided the first successful scientific theory of adaptations. Evolution explains adaptive design on the basis of three principles: phenotypic variation, heritability, and fitness consequences. A phenotypic trait is anything that can be observed or measured. Individuals in a population are seldom identical and usually vary in their phenotypic traits. Furthermore, offspring frequently resemble their parents, sometimes because of shared genes but also because of other factors such as cultural transmission. It is important to think of heritability as a correlation between parents and offspring, caused by a mechanism. This definition will enable us to go beyond genes in our analysis of human evolution. Finally, the fitness of individuals—their propensity to survive and reproduce in their environment—often depends on their phenotypic traits. Taken together, the three principles lead to a seemingly inevitable outcome—a tendency for fitness-enhancing phenotypic traits to increase in frequency over multiple generations” (Wilson 2003: 7).

The radical position that Darwin was advancing in Descent of man was that human traits are all explicable through evolution. This, I might add, is still (unfortunately) a controversial position today among certain groups of people—despite the shocking amount of confirmatory evidence (Lents 2018). I won't attempt to persuade you of the truth of Darwinism here (although it's been said of me that accepting the truth of evolution is a prerequisite to even have a conversation with me). Rather, I'll connect Darwinism to the puzzles we've been looking at in this course.

Recall what we've been calling the puzzle of human collective action: that despite our selfish tendencies, humans also have the capacity to cooperate on a massive scale with other humans who are non-kin and are from different ethnic and racial groups. This seems completely at odds with the popular (but erroneous) conception of evolution as "survival of the fittest." However, as Wilson notes in his Darwin's Cathedral, this puzzle only becomes more perplexing when initially learning about evolutionary theory. Here is what he calls the fundamental problem of social life: individuals who display prosocial behavior do not necessarily survive and reproduce better than those who enjoy the benefits with sharing the costs. Put another way, “[g]roups function best when their members provide benefits for each other, but it is difficult to convert this kind of social organization into the currency of biological fitness” (Wilson 2003: 8). In short, at face value, cooperation doesn't seem to translate well to passing on one's genes to the next generation; so, it seems like an evolutionary dead end.

Befitting of his fame, Darwin was the first to propose a solution to the fundamental problem of social life. Darwin argued that even if a prosocial individual does not have a fitness advantage within his/her own group, groups of prosocial individuals will be more successful than groups who lack pro-sociality. In other words, perhaps it's the case that individual cooperators die without passing on their genes. But(!) groups of cooperators beat groups of non-cooperators. Thus, cooperation spreads.

“It must not be forgotten that although a high standard of morality gives but a slight or no advantage to each individual man and his children over the other men of the same tribe, yet that an increase in the number of well-endowed men and an advancement in the standard of morality will certainly give an immense advantage to one tribe over another. A tribe including many members who, from possessing in a high degree the spirit of patriotism, fidelity, obedience, courage, and sympathy, were always ready to aid one another, and to sacrifice themselves for the common good, would be victorious over most other tribes; and this would be natural selection. At all times throughout the world tribes have supplanted other tribes; and as morality is one important element in their success, the standard of morality and the number of well-endowed men will thus everywhere tend to rise and increase” (Darwin as quoted in Wilson 2003: 9).

In a nutshell, Darwin was making the case that phenotypic variation, heritability, and fitness consequences applied to groups just as much as it applied to individuals. Moreover, this could explain human cooperation, including what we call morality.

Important Concepts

Food for thought...

Legacy

Recall that in Endless Night (Pt. I), we saw the theory of moral sentimentalism put forward by David Hume and Adam Smith. However, this theory was hamstrung even if the two thinkers who conjured up the view did not realize it. What Hume and Smith lacked was a rationale for why and how nature would impart in us a tendency to prefer prosocial cooperative behavior, as well as the tendency to dislike antisocial behavior. Of course, it took another towering genius (Darwin) to provide a theory about the mechanisms by which a preference towards prosocial behavior (at least towards one's ingroup) could be developed and perpetuated: natural selection and group selection. It was the confluence of these two strains of thought, moral sentimentalism and evolutionary theory, that gave rise to the view known as moral nativism: the view that evolutionary processes programmed into us certain cognitive capacities that allow for moral thinking and behavior.

Cognitive scientists, those that work in an interdisciplinary field that traces its origins back to the work of David Hume, refer to our evolutionarily-evolved functions as modules, "programs" that perform some specific cognitive function like language acquisition, our number sense, and our intuitive physics (see Food for thought). Moral nativists, then, could be assumed to be hypothesizing the existence of an innate morality module, and there are many views on just what this morality module entails. Some think that we come pre-loaded with complete moral judgments, like "Don't kill innocents!", while others think that we only come with a general tendency to learn from our environment what is accepted and what is not, what is "right" and what is "wrong" (see Joyce 2007). According to this second theory, much like the universal grammar that allows us to learn languages effortlessly when we are young, the morality module lets us learn moralities in the same way. We "grow" a morality by internalizing and synthesizing the collective views of those we interact with.

So far this sounds much like cultural relativism, and there are thinkers who use evolutionary psychology to defend relativism (for example, Jesse Prinz). Moral nativism is most definitely not a kind of relativism, a topic we will turn to in the next section. It might be noted here that very few thinkers apply any kind of relativistic theory when defending their moral convictions; in fact, they seem to typically prefer Utilitarianism and Kantianism (see Unit II). Instead, what we will discuss here is the following: if there is a morality module, it is very strange indeed. This is something neither Smith and Hume nor Darwin could've foreseen—just how buggy our moral cognition is.

Idiosyncrasies

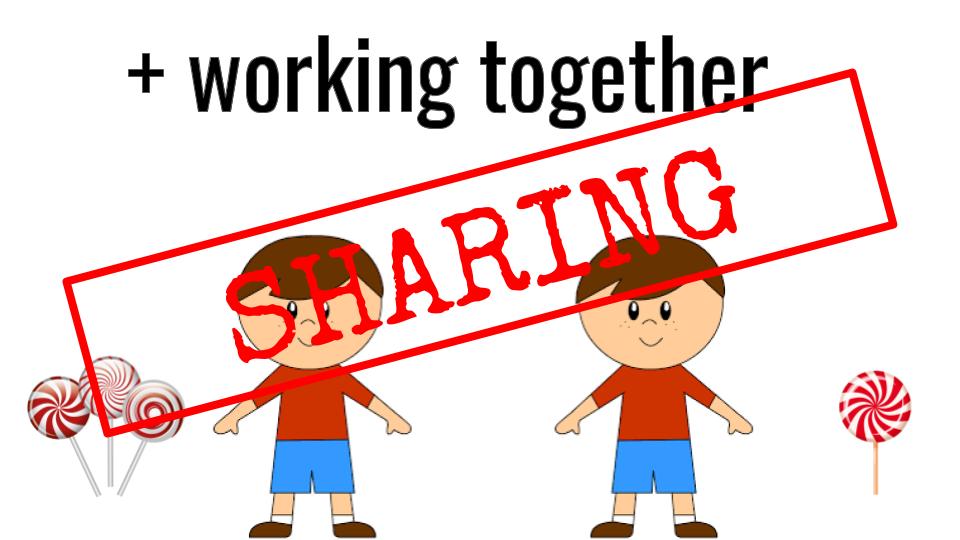

Assuming we do have an innate morality module, our innate moral tendencies do appear to be strange and even inconsistent. For example, Tomasello (2016: 71) hypothesizes that we have an intuitive sense of just rewards but(!) it only kicks in after collaborative activity. In a series of experiments, he tested for a sense of justice in children. In one experimental setup, two children would each get a treat (i.e., candy) but one child would get more than the other. The children in this setup tended to not share. In a second experimental setup, each experiment had two children do some task (i.e., work) and then they were rewarded with a treat. Again, one child would get more than the other. Again, children would mostly not share. But in a third experimental setup, Tomasello was able to get the children to share. What was the difference? In this setup, two children had to work together to achieve the task. Only then would the children share when one child was given more candy than the other. There's something about working together that gives rise to our moral feelings about justice and fairness; absent this cooperation, we are fine with unfairness.

Our capacity for violence also depends on our social environment. Blair (2001) suggests that we have a violence inhibition mechanism that suppresses aggressive behavior when distress cues (e.g., a submission pose) are exhibited. This is why armies do all they can to train soldiers to override their innate dispositions against violence. This is where the sociological comes in. There are various sociological factors that can facilitate violent behavior, such as creating a group mentality and creating distance (both physical and emotional) between the enemy and your group (Grossman 2009). So, it might be innately difficult to harm someone right in front of you, but if you have a group egging you on or if you are looking at "the enemy" through a rifle scope or on a computer screen (as in drone attacks), then it becomes a lot easier. Moral inhibitions, it seems, can be weakened by salient sociological features of the environment.

It's even the case that the types of policies that we favor might be affected by our intuitions about what humans can reasonably be capable of—an example of the tail wagging the dog. For example, Sowell (1987) hypothesizes that our intuitions about human nature and our capacity to predict complex human interactions give rise to our different attitudes towards politics and society. If you take the pessimist side, you might believe that the complexities that arise from, say, raising the minimum wage are too difficult to predict and so the best policy is to not attempt to regulate the economy with such a heavy hand. A good exemplar of this view is F. A. Hayek. On the optimistic side, you might believe that humans can positively influence complex systems like the economy and raise the standard of living for all. Perhaps Marx and Engels are good examples of this optimism; Keynes might fit the bill as well. The important thing to note here is that it is possible that these thinkers' innate tendencies to either be pessimists or optimists are what led to their particular political dispositions (see also Pinker 2013, chapter 16). This is once again the power of our innate dispositions rearing their heads into the moral and political realm. I might add that these innate dispositions are often accompanied with positive and negative feelings. In fact, it is possible that the feelings drive the moral conclusion and our reasoning capacities only invent a rationale for them afterwards (see Kahneman 2011). So, even when you think you have good reasons for your moral conclusions (with economic models included!), that very moral decision of voting for or against the government helping the least well off might be a product of non-conscious intuitions.

Our methods of evaluating whether things are good or bad, a mental faculty that might be relevant in moral evaluations, appears to be non-rational: it doesn't follow traditional linear reasoning. Take as an example the following. The halo effect, first posited by Thorndike (1920), is our tendency to, once we’ve positively assessed one aspect of a person, brand, company or product, positively assess other unrelated aspects of that same entity (see also Nisbett and Wilson 1977 and Rosenzweig 2014). This means that once you know one positive thing about a company, say that their value is up on the New York Stock Exchange, you are more likely to believe that this company has other positive traits, like that they have good managers and a positive workers' culture even though you don't have any information on these other traits(!). It just happens to be that once we believe in one positive trait, our minds tend to "smear" the positivity onto other aspects of that company. This happens with products, people, and ideas too, FYI (see Rosenzweig 2014.

Philosopher Peter Singer comments on how our moral intuitions are only tuned to those scenarios for which they evolved and can't seem to be readily activated in more modern social contexts:

"Our feelings of benevolence and sympathy are more easily aroused by specific human beings than by a large group in which no individuals stand out. People who would be horrified by the idea of stealing an elderly neighbor's welfare check have no qualms about cheating on their income tax; men who would never punch a child in the face can drop bombs on hundreds of children; our government—with our support—is more likely to spend millions of dollars attempting to rescue a trapped miner than it is to use the same amount to install traffic signals which could, over the years, save many more lives" (Singer 2011: 157).

My favorite two examples of the strangeness of our innate morality module (if it exists) are the following. First, Merritt et al. (2010) argue that we are prone to moral licensing. In other words, once we’ve done one good deed, we feel entitled to do a bad one (click here for more info). Second, several studies (e.g., Grammer and Thornhill 1994) show that humans have an innate preference for symmetrical faces, judging these to be more beautiful. This might explain why attractive defendants on trial are acquitted more often and get lighter sentences (see Mazzella and Feingold 1994; click here for a real-world example). The morality module, if it exists, is a fickle faculty indeed.

More(!) Important Concepts

The offspring

Non-cognitivism

A child being spanked.

In addition to moral nativism, the confluence of moral sentimentalism and evolutionary theory has inspired some meta-ethical positions. This is to say that, while one can accept some version of moral sentimentalism (plus an account of a morality module) as the ethical theory they accept, they might also have several meta-ethical positions inspired by their ethical theory of choice. One such view is non-cognitivism, the view that sentences containing moral judgments do not have truth-functionality (i.e., are not propositions) but instead express emotions/attitudes, rather than beliefs. In truth, there are actually various "flavors" of non-cognitivism, but let me get at what they have in common. A sentence like "Spanking your children is wrong" sounds suspiciously like a belief—namely, the person uttering that sentence is saying that they believe the act of spanking children features the property of moral wrongness, just like LeBron James has the property of being 6'9". But, the non-cognitivist argues, it's actually not a belief. It's actually just an expression of emotion or perhaps a command. In other words, when you say "Spanking your children is wrong", the real linguistic function is something like "BOO SPANKING CHILDREN!" or "NO, DON'T SPANK YOUR CHILDREN", either a emotive expression or a command, respectively. The main point of non-cognitivism is this: moral judgments aren't true or false. They're not the kind of thing that can be true or false. So, if you've been thinking this whole course that, say, the sentence "Capital punishment is morally permissible" is false, you're wrong—that sentence isn't the kind of thing that can be true or false. You're just saying "BOO CAPITAL PUNISHMENT!"

Emma Darwin (1808-1896).

Sometimes it's easier to understand non-cognitivism when juxtaposed with moral relativism. The first thing to point out if we want to understand this non-cognitivism is how strange the notion of relative truth is. Relativism is the view that some things have some property in some contexts but not in others. Let's take an example to make this more clear. If we are a relativist about beauty, then we believe that Emma is beautiful for Charles but not beautiful to Alfred. Think about how strange that is: Emma both has the property of being beautiful and doesn't have it, depending on who's looking at her. In any other context, we would rightly say that is ludicrous. I, for example, am not both under and over six feet in height. I can be either one or the other, and that's just it.

So perhaps a better way of understanding beauty might be to think about it more as an expression of one's feelings. In other words, using the jargon learned in the Important Concepts above, judgments regarding beauty are not propositions but instead something more like exclamations. In other words, when someone says "Emma is beautiful" it looks like they are giving a description about Emma (that can either be true or false). But maybe what they're really doing is saying something like "EMMA! WOW!", in a grammatically misleading way. It looks like they're giving a truth-functional description, but all they're saying is "YAY EMMA!" (which is not truth-functional).

So, the non-cognitivist argues, the notion of relative truth is out, and cultural relativism goes out with it. It's absolutely ludicrous, they say, to think that some action (for example, arranged marriage) is perfectly morally permissible in one case, but is absolutely morally abhorrent in another. The notion of relative truth is just too strange. A better position, the non-cognitivist argues, is to say, "This culture says, 'HURRAY ARRANGED MARRIAGE!' and some other cultures say 'BOO ARRANGED MARRIAGE!'" This gets the same sentiment across without meddling with strange theories of truth. Moral judgments, then, are simply expressions of one's feelings.

Moral error theory

While non-cognitivism is a theory about the linguistic function of uttering sentences containing moral judgments, moral error theory is a position about what moral properties are: moral properties, if they really are the way that Kant and others say they are, are non-physical, non-natural, abstract objects. In other words, moral properties (according to moral objectivists) are mind-independent; they've existed independent of humans for all eternity. To this the moral error theorist says "Baloney!" In other words, the moral error theorist focuses on the metaphysical claim that moral objectivists are making, and they say there's just no way those things actually exist. So, it's not the notion of relative truth that's the deal-breaker; it's the weirdness of moral properties (see Mackie 1990).

Let's take an example to make this clearer. Think about the sentence "The number of cups in the cupboard is 5." The truthmaker for this sentence is pretty easy to conceptualize. In fact, you can even visualize it! The truthmaker is: five cups in a cupboard. Any more or any less would make the statement false. This is an easy case because all the elements of the sentence (cups, cupboards, the quantity of five) are perfectly intelligible. Now think of the sentence "Stealing is morally wrong." What is the truthmaker for that? Can you picture it? All I can picture is stealing (sorta). I picture someone running away from a bank with a bag with a dollar sign on it. Where is the wrongness in there? It's not in the bag, right? Money is (to me) morally neutral. It's not in the whole action, since that could easily be a scene in a movie set (with a fake bank, fake bills, etc.), and pretending you're stealing doesn't seem morally wrong. What thinkers like Mackie (1990) claim is that the reason why you can't picture moral wrongness is because it isn't physical. And it isn't just an idea either. Whatever it is, Mackie says, it is really weird. Again, just try to imagine the concept of moral wrongness. Whatever it is, it somehow has the property of not-to-be-done-ness built into it. It sounds strange. It sounds, in other words, completely made up—or so says the moral error theorist. Every moral judgment you've ever made is false because the thing that would make it true (i.e., some moral property) doesn't exist. This is systematic moral error.

“Plato’s Forms give a dramatic picture of what objective values would have to be. The Form of the Good is such that knowledge of it provides the knower with both a direction and an overriding motive; something’s being good both tells the person who knows this to pursue it and makes him pursue it. An objective good would be sought by anyone who was acquainted with it, ...because the end has to-be-pursuedness somehow built into it... How much simpler and more comprehensible the situation would be if we could replace the [non-natural] moral quality with some sort of subjective response which could be causally related to the detection of the natural features on which the supposed quality is said to be consequential” (Mackie 1990: 28-29; interpolation is mine).1

Justification skepticism

A third meta-ethical position inspired by moral sentimentalism and evolutionary theory is justification skepticism, the view that moral objectivism can simply not be satisfactorily defended. The justification skeptic's argument is simple. Here's what you have to ask yourself. Is it possible that evolution somehow predisposed you to make moral judgments and to feel that they are objectively true (even though they're not)? Here's another way to put it. What's more likely: that morality is real and you can use reason (like Kant says) or divine revelation (like some divine command theorists say) to know what's right or wrong? Or that your concepts of right and wrong actually have perfectly natural evolutionary origins and have been expanded upon by cultural evolution? Even if one accepts that evolution imparted in us a morality module, the justification skeptic still argues that, even if moral properties exist, there's no guarantee that our morality module actually targeted and acquired the "right" set of moral values. Sharon Street puts it this way:

“The (moral) realist must hold that an astonishing coincidence took place—claiming that as a matter of sheer luck, evolutionary pressures affected our evaluative attitudes in such a way that they just happened to land on or near the true normative view among all the conceptually possible ones” (Street 2008: 208-9).

Moral skepticism

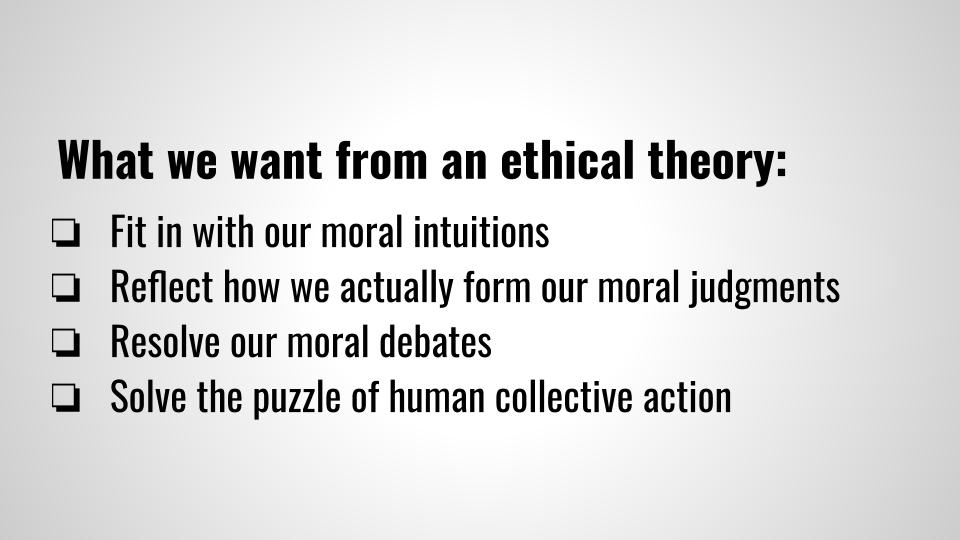

Hume and Smith developed an ethical theory that gave the dominant role in moral judgment to moral sentiments. This view is called moral sentimentalism.

After Darwin, evolutionary theory began to be applied to human affairs, such as the human activity of moralizing.

Hume and Smith's moral sentimentalism has several descendants that arose in the 20th century, including non-cognitivism, moral error theory, and justification skepticism.

Non-cognitivism, moral error theory, and justification skepticism are all forms of moral skepticism, the view that denies that moral knowledge is possible. These are often paired with moral nativism, which posits the existence of an innate morality module that was imparted on us by evolution. Combining all of these views renders a radical moral skepticism that seeks to explain morality in a purely naturalistic, deflationary, anti-realist way.

FYI

Suggested Viewing: John Vervaeke, Cognitive Science Rescues the Deconstructed Mind

Supplemental Material—

Video: Closer to Truth, Donald Hoffman on Computational Theory of Mind

Video: Dan Ariely, Our Buggy Moral Code

Kevin DeLapp, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Entry on Metaethics Sections 1 and 2

TL;DR: Crash Course, Metaethics

Related Material—

Audio: Freakonomics, Does Doing Good Give You License to Be Bad?

Link: Jonathan Haidt, The Moral Roots of Liberals and Conservatives

Video: TEDTalksYuval Noah Harar—What explains the rise of humans?

Advanced Material—

Reading: Paul Thagard, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Entry on Cognitive Science

John Mackie, The Subjectivity of Values

Podcast: Science Salon, Michael Shermer with Dr. Michael Tomasello

Footnotes

1. Mackie’s moral skepticism has been defended and further developed by Richard Joyce in various works, including The Myth of Morality (1998), The Evolution of Morality (2006), and Essays in Moral Skepticism (2016). But Joyce follows a very similar theme: moral objectivism is just too strange to actually be true; there must be a natural way of explaining it.