Eyes in the Sky

An unjust law is no law at all.

~St. Augustine

Making room...

Last time we covered two ethical theories: Hobbes' social contract theory (SCT) and ethical egoism (EE). Of these two, SCT is clearly the more ambitious theory. It seeks to explain both the origins of civil society and our moral judgments; and it grounds the theory in an account of human nature. This last point is, according to MacIntyre (2003: 121-145), Hobbes' lasting contribution to moral discourse: to point out that a theory of ethics has to be grounded in a valid account of human nature. Note, however, that MacIntyre is not agreeing with Hobbes that all of our behaviors are driven by our self-interested nature; rather, he is noting that if we are to produce a viable ethical theory, it must come in tandem with a theory of human nature.

SCT, at least in my way of looking at things, has an edge over EE in another way. In his influential Inventing Right and Wrong, John Mackie (1990) discusses how pervasive Social Contract Theory has been, spanning back millennia. It appears, then, that SCT is intuitively appealing. This is because something about human society, with its built-in complexity and it's hierarchy, seems out of place in nature; no other animals have achieved this level and kind of cooperation (although some insects have come close).1 Mackie acknowledges that it looks like there was a sudden organizing principle given to humans. Law, justice, and morality abruptly appear as mutual agreements to work together, a type of cooperation which is not seen elsewhere in the animal kingdom.

“This [SCT] is a useful approach, which has been stressed by a number of thinkers. There is a colourful version of it in Plato’s dialogue Protagoras, where the sophist Protagoras incorporates it in an admittedly mythical account of the creation and early history of the human race. At their creation men were, as compared with other animals, rather meagerly equipped. They had less in the way of claws and strength and speed and fur or scales, and so on, to enable them to find food and to protect them from enemies and the elements.... Finally Zeus took pity on them and sent Hermes to give men aidōs (which we can perhaps translate as ‘a moral sense’) and dikē (law and justice) to be the ordering principles of cities and the bonds of friendship” (Mackie 1990: 108).

But SCT has its detractors. Despite acknowledging its influence, many thinkers do not believe SCT is accurate or tells the whole story. For example, linguist and developmental psychologist Michael Tomasello (2014) believes that even if SCT is intuitively appealing, is wrong in at least two ways. First off, Tomasello argues that complex social arrangements in human groups could not have arisen due to contracts, since the very act of making contracts itself requires various social conventions. In other words, Tomasello thinks that Hobbes' SCT puts the cart before the horse. Contracts can't be the origin of civilizational complexity since they are only possible once a certain degree of civilizational complexity has already been achieved.

“Some conventional cultural practices are the product of explicit agreement. But this is not how things got started; a social contract theory of the origins of social conventions would presuppose many of the things it needed to explain, such as advanced communication skills in which to make the agreement” (Tomasello 2014: 86).

Second, Tomasello argues that certain psychological capacities would've needed to evolve before any contracts could be made. However, these requisite psychological capacities could not have arisen—or at least did not arise—in a species with purely egoistic motives. According to Tomasello's theory, it looks like the evolution of our capacity for language required that we first evolve the capacity to act for the benefit of others, at least sometimes. This is why human language is, more often than not, informative, in some sense: because we evolved to give truthful information to each other. In non-human primates, on the other hand, communication typically takes the form of imperatives, i.e., commands. And so, humans first evolved the capacity for non-egoistic motives along with language, and then humans started making contracts. In other words, a pillar of SCT, psychological egoism, might turn out to be false.

Tomasello's point is well-taken. But it gets worse if we look at data from other empirical disciplines. As Singer (2011: 3-4) points out, fossil finds show that five million years ago our ancestor Australopithecus africanus was already living in groups. So, Singer concludes, since Australopithecus did not have the language capacities and full rationality requisite for contracts, then it’s clear that contracts are not a necessary antecedent to social living, like Hobbes, Rousseau and others have argued.

Another criticism of SCT comes from the study of history. New evidence is leading deep history scholars to the conclusion that the earliest states could not hold their population; they had to use coercion to reinvigorate their pool of subjects. Scott (2017) attempts to dispel the notion that states came first, and then the state bureaucracy facilitated agriculture. Nothing could be further from the truth. Scott notes that there are instances of agriculture that pre-date the formation of states by as much 4,000 years, thereby discrediting the notion that state formation is what facilitated agriculture. And so, although the timeframes varied by region, in general, there was a several thousand year period during which humans were practicing agriculture, but there was not yet a centralized authority.

Scott explains that earlier scholars, not unreasonably, projected the aridity of Mesopotamia of recent history back to ancient times and figured only states could’ve facilitated this process. In other words, when we look at where the earliest states formed (Mesopotamia), we look at how dry it is now and figure that it's been dry all along. We naturally infer that only state bureaucracies could've arranged for the coordination needed to irrigate those lands. However, now we know, through climate science, that the region was not arid back then; we can see more clearly that agriculture came first, and then (for some other reason) came the earliest states.

If true, this looks like Hobbes' account of how early states formed is false. It was not a mutual agreement to establish a common authority; instead, it was more like a coalition of warlords who forced subjects to settle in their lands. We now call these warlords the government.2

“If the formation of the earliest states were shown to be largely a coercive enterprise, the vision of the state, one dear to the heart of such social contract theorists as Hobbes and Locke, as a magnet of civil peace, social order, and freedom from fear, drawing people in by its charisma, would have to be re-examined. The early state, in fact, as we shall see, often failed to hold its population. It was exceptionally fragile epidemiologically, ecologically, and politically, and prone to collapse or fragmentation. If, however, the State often broke up, it was not for lack of exercising whatever coercive powers it could muster. Evidence for the extensive use of unfree labor, war captives, indentured servitude, temple slavery, slave markets, forced resettlement in labor colonies, convict labor, and communal slavery (for example, Sparta’s helots) is overwhelming” (Scott 2017: 25-9; emphasis added).

All this to say that SCT has some problems. As of now, we are leaving the status of the truth of psychological egoism as an open question. And so we move towards another ethical theory, this one having to do with supernatural beings...

Divine Command Theory

Divine Command Theory (DCT) is easy to summarize. Just as it was the case with SCT, the moral discourse behind DCT goes back millennia. We will be covering the version of DCT that was most popular in the Middle Ages, as embodied in the work of William of Ockham (ca. 1287 to 1347). Nonetheless, it should be clear that there are hints of this view far back in the history of Philosophy, as evident in Plato's dialogue Euthyphro, as well as long after Ockham, as in the work of Martin Luther. The following is taken from Keele's (2010) intellectual biography of Ockham who begins his book with the historical and ideological context into which he was born.

Per Keele (2010: 27), DCT typically entails the following theses:

- God is the source of moral law.

- What God forbids is morally wrong.

- What God allows is morally permissible.

- The very meaning of “moral” is given by God’s commands.

In a nutshell, the divine command theorist argues that morality has no cause but God. Morality simply is what God has stipulated it to be.

The Strangeness of DCT

Some people initially don't see how counterintuitive DCT really is. They think they understand it, but they haven't thought the whole thing through. To show you the strange of implications of DCT, we can look at an ancient debate between Socrates and Euthyphro from Plato's dialogue Euthyphro. The setup of the dialogue is not terribly important (although you can watch this video if you are interested). The important part is that, in a conversation on what piety means, Socrates corners Euthyphro into a strange dilemma.

Stealing, which, according to

divine command theorists is

only wrong because God

said it is wrong.

To better understand this dilemma, let's do two things. First, let's not talk of "gods". The Greeks were polytheists, but most people reading this are probably not. We'll assume monotheism (belief in one god) here.3 Second, let's replace the word piety for morality. So then, the dilemma that Euthyphro finds himself in is that either he defines morality as being invented by God or he defines morality as independent of God (but still being a code that God wants you to follow).

The first option makes morality very strange. It makes it so that some actions are wrong only because God said so. Had God not said anything, they would've been permissible or even morally required. But it seems obvious some things, like murder, are wrong no matter what. The second option doesn't actually define morality. It just tells you that God isn't directly involved with its creation but that God still wants you to follow moral rules. The divine command theorist bites the bullet and chooses the first option.

“[For Ockham and other divine command theorists], God, by his absolute power, was so free that nothing was beyond the limits of possibility: he could make black white and true false, if he so chose: mercy, goodness, and justice could mean whatever he willed them to mean. Thus not only did God’s absolute power destroy all [objective] value and certainty in this world, but his own nature disintegrated [in terms of the capacity for rational reflection]; the traditional attributes of goodness, mercy and wisdom, all melted down before the blaze of his omnipotence” (Leff 1956: 34; interpolations are mine).

There are a two more ways in which DCT is strange. First off, it seems to trap believers in a maze of circuitous reasoning. How so? Notice that the divine command theorist argues that moral values can only be grounded in God’s commands. However, they also (typically) argue that God is good. But(!) the very meaning of good was established by God. And so, it seems as if God basically defined his way into being good. And so, there appears to be no non-circular way of arguing that God is in fact good.

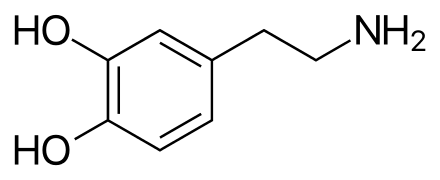

The third way in which DCT is strange is in what it makes out moral properties to be. Recall that for Hobbes and Glaucon, good could be equated with pleasure. Although this is questionable—as we will see when we cover David Hume—there is something appealing in this view, which we've been referring to as hedonism. What's appealing about hedonism is that it is a form of naturalism: the view that moral properties are natural properties. Why is this appealing? Because it certainly is the case that we at least know what pleasure is. We know it has to do with neurotransmitters in the brain, we know the kinds of things that give rise to pleasure (calorie-rich foods, sex, etc.), and we can come to know even more about it with the help of science. However, now think about what DCT says moral properties: they're actually God's commands. They are the proclamations of an all-powerful, supernatural being. Can you even begin to picture that? Can you really wrap your mind around understanding a divine command? If naturalism is true, then all is well and good; I can picture, say, dopamine. I even know it's chemical makeup (see image). But if DCT is true, then moral properties become a little less intelligible. Moral properties, in other words, turn out to be non-natural properties: non-physical, abstract, and invulnerable to being probed by the sciences.

Sidebar

An argument for DCT from moral properties

Interestingly enough, the strangeness of moral properties that DCT endorses could actually be used to motivate an argument in support of DCT. The argument is that non-naturalism gives the best account of why morality must be followed. Let me give you an example...

Imagine something you really think is morally wrong. Ok, now what if I ask you, "Why am I not allowed to do that thing?" What if you say, "Well, it's because it would make someone unhappy." If I were a real psychopath, I could say, "I kinda don't care." You try saying other things too. Maybe you'd tell me that it's not in my best interest, or that it is against the law. I can respond in the same way. "That doesn't matter to me." But what if instead you told me that there is an all-powerful being who told all of us that we cannot perform the action in question. Moreover, if I break this rule, I will suffer punishment for all eternity, I would live and re-live unthinkable horrors in a lake of fire. THAT might get me to think, "Hmmm... maybe this action shouldn't be done after all." There's something about moral predicates (like "______ is morally wrong") that assumes something supernatural is going on. It seems like the property of moral wrongness has not-to-be-done-ness built into it. It's hard to express this, but the idea is that, if you really believe something is morally wrong, you're likely not to do it. And it's hard to explain this with something simple and natural, like pleasure or the law. It's something else. Something divine.

Strange bed fellows...

Perhaps the best support for DCT I can give you is to inform you that even some atheists buy into this view. Let me explain. Some thinkers (e.g., Joyce 2016) both reject the notion of a supernatural being (atheism) and also argue that there is something descriptively accurate about DCT. To be clear, normative claims are those claims which prescribe how something or someone should be. For example, "You should wash your hands" is a normative claim. It's a claim about what you ought to do. Descriptive claims are those claims which merely purport to describe how something or someone actually is. For example, "Your hands are dirty" is a descriptive claim.

Joyce argues that DCT is normatively false, because there is no God, and so God doesn’t actually command anything. In other words, there isn't really something you ought to do because there are no supernatural beings actually commanding you to do it and threatening you with eternal damnation if you don't. But DCT is descriptively accurate, in that the force of moral concepts does seem to come from supernatural beings (as if they actually existed). In the words of a thinker with views similar to that of Joyce's: the world is, of course, entirely natural, but we have non-naturalistic ways of thinking about it, such as moral predicates (see Gibbard 2012: 20-1).

Let me put this in the simplest terms. Some people believe that morality comes from God. Call this DCT (theist version). Other people believe God doesn't exist. But they also believe that the idea of God had to be invented at some point, and right around when that happened the idea of morality was also born. And so DCT is sort of right: God did invent morality. It just happens to also be the case that we invented God; neither God nor morality are actually real. Call this DCT (atheist version). You can find more support for both theories in the Food for Thought below.

Food for thought...

DCT & Non-Naturalism

Problems with DCT (theist version)

The Contradiction Argument

This argument comes from Randy Firestone's Critical Thinking and Persuasive Argument (see his chapter on religion). We've been assuming thus far that religions have a coherent, non-contradictory moral code. But, for example, the moral precepts in the Bible form an inconsistent set; i.e., they contradict each other.4 Hence, it is unclear just what God’s Law is. Consistency, or internal coherence, as we've seen, is a theoretic virtue, and DCT seems to be lacking.

The Moral Argument

This argument also comes from Firestone's Critical Thinking and Persuasive Argument. The argument is this: It appears that some of the moral precepts in the sacred scriptures of some religions, for example the Bible, can only be described as morally abhorrent. Hence, DCT renders itself extremely counterintuitive. For example, the Bible seems to advocate:

- genocide (see Deuteronomy 7),

- the prevalence of capital punishment (for example, see Leviticus chapters 20-21),

- misogyny (see 1 Timothy 2:11–14),

- strange marriage customs, as when Abraham (the common patriarch in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) marries his half-sister (see Genesis 20:12), and

- there even appears to be a prescription for abortion if a woman has been unfaithful (see Numbers 5: 11-31).5

Problems with DCT (atheist version)

Lingering Empirical Problems

The problems for DCT (theist version) all apply to the atheist version as well. Why would the invention of an inconsistent moral code get people to behave more cooperatively? Moreover, there are deeper empirical problems. Why should you feel closer to someone who has similar supernatural concepts? To simply posit that the invention of “Big Gods”, i.e., gods that are morally concerned and threaten to punish those who break moral and social norms, led to greater cooperation in society fails to detail just which cognitive mechanisms lead to this prosocial behavior and why. In other words, the "Big Gods" hypothesis has some challenges, and it's not clear that it can overcome them (see Boyer 2001: 286). Stay tuned.

Hobbes' social contract theory is vulnerable to several criticisms. For example, a. it appears that complex—and perhaps even cooperative—social life predates the linguistic and intellectual capacities contracts; and b. it is unclear whether psychological egoism is true.

Divine command theory (DCT) is the view that God is the arbiter of morality; i.e., what is moral is what God has commanded.

Bringing DCT into the mix ushers in a new distinction: moral naturalism and moral non-naturalism. Moral naturalism is the view that moral properties are actually natural properties. Hedonism is an example of this view. Moral non-naturalism is the view that moral properties are non-natural (i.e., non-physical, like souls or God). DCT appears to imply that moral properties are non-natural.

In this course, we will be covering two versions of DCT: the theist and the atheist version. The theist version is straightforward in that it is simply the view that a. God exists, and b. God stipulated a moral code for everyone to follow. The atheist version is a. the denial that God exists, but b. the admission that belief in supernatural beings (and the desire to obey their commands) are an integral part of moral discourse.

FYI

Suggested Reading: Steven Cahn, God and Morality

TL;DR: CrashCourse, Divine Command Theory

Supplementary Material—

-

Reading: Michael Austin, IEP Entry for Divine Command Theory

-

Video: Transliminal, Interview of Ara Norenzayan

Related Material—

- Reading: Charles Tilly, Warmaking and statemaking as organized crime

Advanced Material—

-

Reading: Plato, Euthyphro

-

Reading: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Entry on Ockham

-

Note: Read Sections 1, 2, and 6

-

For historical context on William of Ockham, the interested student can also read Gordon Leff’s, The Fourteenth Century and the Decline of Scholasticism

-

-

Book: Ara Norenzayan, Big Gods

Footnotes

1. Some are a little too quick to compare ant colonies with human civilization. I am an admirer of ants, I should admit; but there are important differences. First off, ants are not conscious in a way even remotely approaching that of humans. Second, the cooperation you see in ant colonies makes evolutionary sense since the ants are all genetically related; they're siblings. Sure, this is not the case in all species of ant, but there are better explanations for human cooperation that don't involve the analogy to ants. Stay tuned.

2. The views of James C Scott are very interesting. You can see a lecture by him here. In this talk, he discusses the view that the planting of grains domesticated sapiens, and he refers to the earliest states as "multi-species re-settlement camps". Also of interest might be the work of Charles Tilly; see the Related Material section.

3. My apologies to the Wiccans.

4. I've linked an easily accessible compendium of the inconsistencies in the Bible here. Of course, there are more academic sources. I'd recommend the work of biblical scholar Bart Ehrman, in particular Misquoting Jesus and Lost Christianities.

5. Sometimes students object that these are all coming from the Old Testament. This is not the case. The First Epistle to Timothy is written by Paul and is housed in the New Testament. Let's not ignore the obvious fact that some people who object this way don't know which books of the Bible belong in the Old and New Testaments. But more importantly, this doctrine (known as Supersessionism) isn't without its critics. Why would the whole first half of a book not be valid once the second half is written? In any case, this topic is best covered in a Philosophy of Religion course.