In Silico

Descartes was mistaken. It’s not so much, “I think, therefore I am.”

More, “We are, therefore I think.”

~Kevin Dutton

Coming around the bend

In today's reading, Socrates and friends discuss various threats to the pursuit of truth. The one we will focus on in this lesson is the power of the crowd. In particular, we will look at the power of social identity and how it can determine your beliefs. Put differently, we're going to look at cases where social identity appears to determine one's beliefs (without them realizing it). Just like in The Family and The Distance of the Planets, our case study will involve a political affiliation. In those earlier lessons, the political affiliation was a far-left ideology. In the next two lessons, the example will come from the right wing of the USA: American conservativism. Let's get started.

Adam Smith (1723-1790).

Just like far-left ideologies render one incapable of even entertaining certain ideas—like genetic influence on, say, intelligence (and what can be done about it)—far-right ideologies do the same for other ideas. I will make my case backwards, so to speak. I will first give you the conclusion of my argument, i.e., what ideas far-right conservatives can't seem to begin to process, and only after stating my conclusion will I give my evidence.

So, here's the first thing that far-right ideologies might render one incapable of processing in an even-handed way: the potential of the government to play an important role in market systems. We'll refer to this as free-market fundamentalism. Just like Marxist tendencies are only exhibited by a small minority of the left-wing in the USA, free-market fundamentalism is not representative of the entire right-wing. In fact, for many conservatives, their allegiance to the right-wing comes from their views on social issues, such as in their opposition to abortion and their view that marriage is a stabilizing institution in society. Having said that, it is undoubtedly the case that some conservatives are free-market fundamentalists—and perhaps there's even more of these than there are Marxist leftists.

What beliefs does free-market fundamentalism entail? Typically, fundamentalists of this stripe believe that a. unregulated capitalist policies can solve many if not all social and economic problems, and b. that government intervention in social and economic problems is doomed to fail (either because government is not motivated by the profit-motive, or because it is inept, or because it is too slow and inefficient, etc.). These first two beliefs are generally accepted by most people who understand the label "free-market fundamentalism". I'd like to add one more belief. In my experience, free-market fundamentalists mythologize and/or distort the views of certain intellectual figures so as to make it seem like these thinkers endorse their views. For example, some free-market fundamentalists I've spoken with argue that the philosopher and economist Adam Smith agrees with their views. Let me say this unequivocally: Smith was not a free-market fundamentalist. I've actually read every book that Smith published. (It was easy. It's only two.) Although he does express wonder at how free-market systems operate, he in no way endorses having no regulations put on markets. Moreover, he has quite a few negative things to say about what he calls "commercial societies" (see Endless Night (Pt. I)). Another figure that these dogmatists sometimes lump into their camp is Friedrich Hayek. However, Wapshot (2012, chapter 14) reminds us that Hayek, although a formidable opponent to Keynesian economics and staunch defender of the free market, nonetheless advocated the following state-sponsored interventions: universal health care, unemployment insurance, and state provisions for basic housing.1

Is free-market fundamentalism an untenable view? Probably. First of all, consider that even if it turns out that all actually existing political arrangements are wasteful, inept, inefficient, or whatever, that doesn't mean that all possible political arrangements have to be. Moreover, it appears that there's evidence from the social sciences that at least one of their beliefs is false: belief (b) above. Recall from the lesson titled Fragility the work of Mariana Mazzucato. In The Entrepreneurial State, Mazzucato argues against the view that the state should not interfere with market processes. She argues instead that the state has played the main role in the development of various technologies that define the modern era: internet, touch-screen technology, and GPS. It has also granted loans to important companies such as Tesla and Intel. Moreover, the state takes on risks in domains that are wholly novel and in which private interests are not active, such as in space exploration in the 1960s. It is a major player both in the demand and supply side, since it both makes many purchases from the private sectors as well as supplies many goods and services. It also creates the conditions that allow the market to function, such as in the building of roads during the motor vehicle revolution. In short, the state is entrepreneurial (and very good at it).

If you recall, I had discussed Mazzucato's work while discussing lazy thinking. Lazy thinking occurs when when you are satisfied with the quick and easy solution without making sure you're actually engaging the more rigorous information-processing parts of your mind. There are signs that free-market fundamentalists, although they are not necessarily lazy, are engaging in lazy thinking. In my experience, when they respond to objections to their dogma, they'll give simple-minded explanations while avoiding the hard cognitive labor of asking themselves how it is that they truly arrived at their conclusion (a process called meta-cognition).

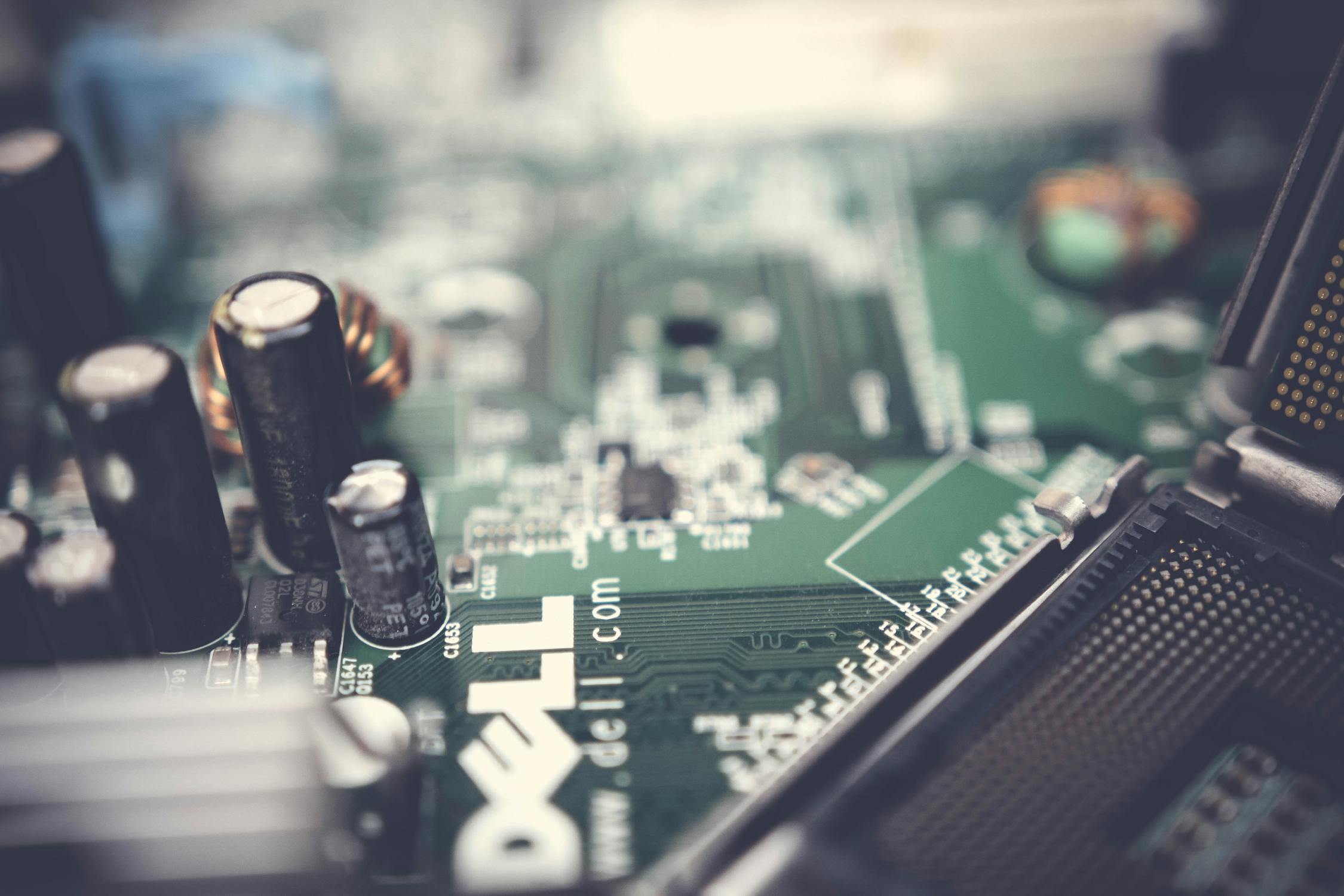

Here's an example. When facing challenges to free-market fundamentalism, the fundamentalist sometimes gives what I call the doom objection. This is the objection that in the past government has always failed when attempting to solve societal problems, and, even when they haven't failed, the private sector could've done it better, faster, and for less money. Ultimately, they conclude, government just gets in the way. Unfortunately for them, that's not true. Mazzucato (2015, chapter 3) provides evidence that the US government not only plays a vital role in the market (by being the biggest consumer of many products), but also has made new markets(!) for radical new technologies that private firms wouldn’t and couldn’t have developed on their own, including those of nuclear energy, computer science, biotech, nanotechnology, and more. I cannot overemphasize this. Let me just focus on computing—a field near and dear to my heart—for a second to really make this point. The computing revolution that we're currently enjoying was made possible by governments. During World War II, governments poured money into the research and development of computing machines. Then, during the Cold War, the US government poured money into furthering these computing devices, funding the computer science departments that cropped up all over the country. And even after the fall of the Soviet Union (and hence the end of the Cold War), the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), which is a research and development agency run out of the United States Department of Defense, played a role in the development of weather satellites, GPS, drones, stealth technology, voice interfaces, the personal computer, and the internet. In short, not only is the state an effective player in the market, it has literally made new markets. Only an incurable degree of extreme confirmation bias lets the free-market fundamentalist not realize this.

Free-market fundamentalists, in my experience, also have this odd, cultish perspective towards entrepreneurs—unless, of course, those entrepreneurs are involved with the government somehow. They argue that only completely de-regulated markets are fair. Taxing, minimum wages, and all other regulations are just a burden on the capitalist entrepreneur, who deserves all the credit since his/her idea got the business off the ground. As someone who one day hopes to own a business, I do admire entrepeneurs. However, the examples that free-market fundamentalists have given me during our conversations betray the fact that they have no idea what they're talking about. For example, I've often been told that Steve Jobs is the ultimate entrepreneur—that his ideas revolutionized the world and that's why he was so rich. Unfortunately, again, the story is a little more complicated. In chapter 4 of The Entrepreneurial State, Mazzucato argues that Steve Jobs’ business savvy is impressive, but it’s still a fact that the base technologies that catapulted his platforms (e.g., iPhones, iPads) to success were developed over decades by the state: touch-screen, GPS, and the internet. Apple (merely) integrated these technologies. Again, the computing revolution was set off by state-funded computer science programs in universities and private-public partnerships. Second, Apple itself received state grants for emerging small businesses. Third, the enabling technologies of Apple products were all invented outside of Apple (by state-sponsored programs). Lastly, Apple even called upon the US government to help breakdown international trade barriers (with Japan) and to purchase their products for American public schools. So, even though Jobs was an impressive individual, his story does not support the idea that the free-market should be completely unregulated and the state should play no role in the market.

My friends, the world is hard. You can't operate under simplistic ideologies and expect to get at the truth. The truth is always more nuanced and complicated and frankly boring. Why do so many people go astray so easily? Why do these dogmas get propagated? Stay tuned.

In-group bias

In the last section, we took a look at a social identity (far-right conservativism) and then identified a dogma that it is particularly easy for this social identity to subscribe to (free-market fundamentalism). In this section, we will begin to make the case that it is the social identity that caused the belief in the dogma—not the other way around, as one might intuitively suspect. Ultimately, it appears that the capacity of crowds to shortcircuit our information processing systems comes down to the in-group bias. In-group bias is the tendency for people to give preferential treatment to others who belong to the same group that they do. Although the word "tribalism" is amenable to misinterpretation (and is not generally considered politically correct), it is a helpful label for the in-group bias. We generally prefer our "tribe", our people, over "them", whoever "they" may be.

A Sphex wasp

(see Sidebar).

Let me first try to persuade you that this is truly important to you and to anyone you care about. I think the best way to do this is to inform you that advertisers, politicians, employers, and many others use in-group bias to manipulate you. In his best-selling Influence, Robert Cialdini reviews the psychology of persuasion, how companies and salespeople try to persuade you, and how to stop yourself from being manipulated. Cialdini begins his survey of the psychological literature by arguing that we have built-in cognitive tools that make us assent to a request, automatically and without thought, once they are engaged. In other words, we appear to be predisposed to assent (whether it be in the form of agreeing, cooperating, buying, or generally responding positively) under certain circumstances, and that these responses happen without conscious thought. We are much like mother turkeys who have their mothering behaviors activated by their chicks cheep cheep sounds (something which is referred to as a fixed action pattern by biologists). If someone presses the right buttons and we aren't paying attention, they can get us to agree with them reflexively. This is part of our cognitive setup—and advertisers and salespeople know this.

Here's an example. Cialdini cites one study where subjects let someone cut in line as long as the cutter gave them a reason when they asked to cut, even if the reason was not really a reason at all. In other words, whether the cutter said, “May I please skip ahead because I am really in a rush” or “May I please skip ahead because I really need to make copies”(!), subjects were inclined to let her cut. Of course, anyone who is standing in line to make copies really needs to make copies. So the experimenter didn’t give the subjects any new information when she said what she said in the second condition. Nonetheless, they let her jump ahead! That's because we predisposed to assent when someone gives a reason for their action. (Try it.)

Of course, Cialdini's principles of persuasion and review of the psychological literature give much more detail than I can here. What is important to note is that built-in tendencies to assent are part of a system of heuristics (or mental shortcuts) that we seem to come pre-loaded with. As we've discussed many times before, processing information is metabolically costly and cognitively demanding. If your brain can, it will skip the processing and arrive at a conclusion from limited information (regardless of the quality of the information). More importantly for our purposes, one of the shortcuts the brain takes has to do with crowds. In fact, the social influence of others appears throughout his book (but see chapters 4 and 8 in particular). Paying attention yet?

The interested student can check out Daniel Dennett’s Intuition Pumps (p. 397-98) for an example of the fixed action pattern of the Sphex wasp. Apparently, the Sphex wasp has to engage in its procedure for laying eggs exactly in the way its genes require it to. In particular, it paralyzes a cricket, drags it outside its burrow, then leaves it at the threshold of the burrow to check that everything is set up inside, and only then drags the cricket back in. When researchers would drag the cricket a few inches while the wasp was checking everything was in order inside, the wasp would drag the cricket back to the threshold and repeat the check-up in the burrow. In other words, the cricket had to be exactly at the threshold where the wasp left it in order for the next behavior to be engaged. Researchers once repeated this little trick on a wasp forty times, and the wasp never thought to drag the cricket straight in. This is the kind of built-in behavioral programs to which Cialdini compares our tendency to assent to: they're automatic. At least in the case of the wasp, they cannot be overridden. It's just like a computer program. You click. It runs. However, things can be different in humans. The first step is learning about the psychological principles of persuasion.

In chapter 8 of Influence, Cialdini focuses on in-group bias. He reminds us that we all automatically and incessantly categorize those around us into those to whom the pronoun we applies and those to whom it doesn’t. As we learn from Dutton (2020), this might be a method for processing incoming information more quickly and efficiently (see lesson titled The Distance of the Planets). In any case, those who we consider part of our “tribe” get many non-conscious psychological benefits: we consider them more trustworthy, we are naturally more cooperative with them, and we even find them to be more moral and humane. This tendency runs deep. When subjects in an fMRI scanner are asked to imagine “the self”, the same neural circuits light up as when they are asked to imagine a close other, i.e., a member of their "tribe". Cialdini even reports that some researchers have gone as far as claiming that tribalism isn’t a part of our nature—it is(!) human nature. This explains why we can see group activities, like choreographed dances, far back in prehistory, as seen in cave paintings.2

This ingroup bias is made manifest in many ways. Importantly, it is typically non-conscious. This is why compliance professionals use it, and why Cialdini discusses it in his book. For example, in Ghana, where taxi fares are haggled before the ride takes place, taxi drivers give better deals to those from their political party. Referees in international soccer matches are more likely to make favorable calls for teams with a sizable proportion of members of their ethnic group. It's even in the Bible! Recall that the Israelites were instructed to only enslave non-Israelites (Leviticus 25: 39-46); a message that was echoed by Plato who suggested that Greeks only enslave non-Greeks and not fellow Greeks. How can this be used to manipulate you? In general, if you can be made to believe that your in-group favors something, then you're very likely to favor that thing too, whether it be a political candidate, a product, a company, whatever.3

My favorite example of this comes from Lilliana Mason's Uncivil Agreement, where she makes the case that Americans are dangerously polarized and self-segregated despite the fact that their political positions aren’t really as different as they perceive them to be (at least for the majority). To be clear, at the extremes, there's basically no hope for reconciliation. But(!) most people are not at the extreme political poles. Mason shows that most people, i.e., more than half, are more centrist and actually agree on a lot, whether they identify as Democrat or Republican. However, what's truly concerning is this: people aren't really thinking about their positions. Most of these centrist just side with whatever their party says without reflecting on it very much (i.e., lazy thinking). The results would be funny if they weren't so tragic. Let's consider an example.

In one study, Cohen (2003) found issue positions to be highly dependent on group and party cues. In one experiment, he was able to get liberals to support a harsh welfare program and conservatives to support a lavish welfare program by telling them their in-group party supported the policy. Did you catch that? Liberals agreed to a pretty conservative policy just because they were told the Democrats endorsed it. Ditto for conservatives. If they were told that Republicans endorsed a pretty blatantly liberal policy, they would endorse it too. This is clearly no good. It almost suggests that these subjects don't really know what the labels conservative and liberal mean. All they hear is "Us" and "Not Us". Lazy thinking. And it gets worse:

“Notably, these respondents did not believe that their position had been influenced by their party affiliation. They were capable of coming up with explanations for why they held these beliefs” (Mason 2018: 74; emphasis added).

In other words, they were completely oblivious about their lazy thinking! Mason continues with the sad reports:

“A Pew poll from June 2013 found that, under Republican president George W. Bush, 38 percent more Republicans than Democrats believed that NSA surveillance programs were acceptable, while under Democratic president Barack Obama, Republicans were 12 percent less supportive of NSA surveillance than Democrats” (Mason 2018: 74).

This is the same set of NSA surveillance programs. The primary difference is who's in charge. One could argue that a Democrat might be more comfortable with the NSA's capacities if they know a Democrat is the executive. However, given the social psychology we've been looking at, it's more tempting to say that they don't know anything about the NSA programs. They just know who's in office. And as such, they simply approve of the programs when their person is in office and disapprove when their person is not in office. Lazy thinking.

Mason gives one more example. It even turns out that one is more likely to become politically active about some issue if there is a strong social movement behind it, regardless of how they rank the issue on a political importance scale (Mason 2018: 121). Let me explain. People ranked issues according to how important they thought they were. Then they were given an oppoortunity to participate in some political event. Even if they ranked the issue low in importance, they would agree to participating in the event if there was a sizable amount of people from their in-group participating. So, even after they said it doesn't matter that much, their in-group bias kicks in and they just go with the crowd.

In conclusion, crowds are not good for your brain.

- Read from 491d-502d (p. 185-197) of Republic.

Free-market fundamentalism is the view that a. unregulated capitalist policies can solve many if not all social and economic problems, and b. that government intervention in social and economic problems is doomed to fail.

Mariana Mazzucato argues against free-market fundamentalism by making the case that the state is actually a very effective entrepreneurial force.

In-group bias is the tendency for people to give preferential treatment to others who belong to the same group that they do.

There is evidence that when we are faced with uncertainty, we turn to our in-group for guidance on what to believe, without processing the information at all.

FYI

Suggested Reading: Mariana Mazzucato, The Entrepreneurial State

TL;DR: TEDTalks, Mariana Mazzucato - The Entrepreneurial State

Supplemental Material—

-

Video: New Economic Thinking, Mariana Mazzucato: How the State Drives Innovation

Related Material—

-

Video: Influenceatwork, Science Of Persuasion

-

Video: 60 Minutes, Ingroup Bias in Babies

Footnotes

1. By the way, Hayek also promoted free movement of labor across state lines, i.e., open borders—an idea that hardly resonates with most conservatives.

2. In chapter 9 of Demonic Males Wrangham and Peterson begin the chapter agnostic about whether violence is genetically-implanted in humans. They then discuss how, although it doesn’t initially seem like it, the male anatomy is designed for fighting. Male arms and shoulders, just like in chimps, are more muscular than the female equivalent and the shoulder joint is suited for punching. Moreover, males and females initially have similar upper bodies, but male muscle begins to set in at puberty, when the female reproductive capacity begins. Interestingly, humans also use their reasoning faculty for violent ends. Most relevant to us here, the authors then move to discuss our in-group bias, and how it only makes sense in a species with an evolutionary history of group fighting. We are so groupish that humans even feel a state of ecstasy when they lose themselves in the collective "Us"—a phenomenon known as deindividuation.

3. Cialdini also discusses how the in-group bias can be used to benefit the species by fostering cross-group cohesion. Cialdini suggests we can begin with children. Members of other ethnic (or religious or political) groups can be invited over for dinners, extended stays, play dates, etc. Importantly, they are not to be treated like guests. They are to be treated like family, such that they are expected to help out, be a part of chores and games, etc. This will develop a feeling of unity with people that are outside of the child’s perceived in-group, thereby extending in the child's mind who counts as we.