Know Yourself

Knowing others is wisdom.

Knowing oneself is enlightenment.

~Laozi

Metacognition

Key to critical thinking is understanding your own thought-processes, something known as metacognition. Many of us are satisfied with accepting our desires and beliefs as they arise in consciousness. Many of my beliefs, like my belief that my home is still where it was when I left the house this morning, are held and/or formed outside of conscious awareness. Here's what I mean by that. I'm not sure that I believe that my home is still where I left it this morning. In other words, if you were to ask me "What do you believe?", I'm not sure that the sentence "I believe that my home is where I left it this morning" would be one of the first ten things to come out of my mouth. I'm not even sure it'd be one of the first 100 beliefs that I would list. (Heck, I'm not even sure I would take your question seriously!) If I'm being honest, if you were to ask me if my home is still where it was this morning, I'm not sure that I actually "held" that belief (whatever that means) prior to being asked about it; it's perfectly possible that I didn't "form" the belief until right after you asked me. So maybe there's some beliefs that I "hold" at the present moment, that I didn't really "form" until they were brought up in conversation.

If you followed what was going on in the paragraph above, then you can see what one type of metacognition is like: it is simply the tracking of belief and the monitoring of belief formation. It's actually kind of cool when you start trying it out. Unfortunatley, metacognition is a whole class unto itself, most adequately taught not by yours truly but by a psychologist. Nonetheless, we can mention some recent findings from the mind sciences that relate both to metacognition as well as to good critical thinking. They have to do with the function of reason.

Take a look at the chair pictured here. It looks uncomfortable, doesn't it? First off, the seat is way too low. Imagine having to do a deep squat every time you want to sit down, not to mention getting up. Moreover, because the seat is too low, it would be impractical to use this chair at the dinner table. You probably wouldn't be able to reach your food. It also just looks weird. It looks like someone cut off a regular chair's legs. Overall then, it's not a good chair. That is to say, it does not satisfactorily perform the typical functions of a chair.

What if I told you it's not a chair? Let me tell you what it really is: it's a kneeler (also known as a prayer chair). You don't sit on it; you kneel on it. The cushion on the top of the chair is for resting your arms during, say, the praying of the rosary. When looked at in this way, clearly this prayer chair performs its function rather well. It actually looks like an excellent kneeler—if only a little old.

Now that you see what this chair is for, you can see that it does its job very well. When you thought it was for sitting, you thought it didn't do its job very well. We can generalize from this. Only when you understand the intended function of an artifact can you assess whether or not the artifact is performing its function well.

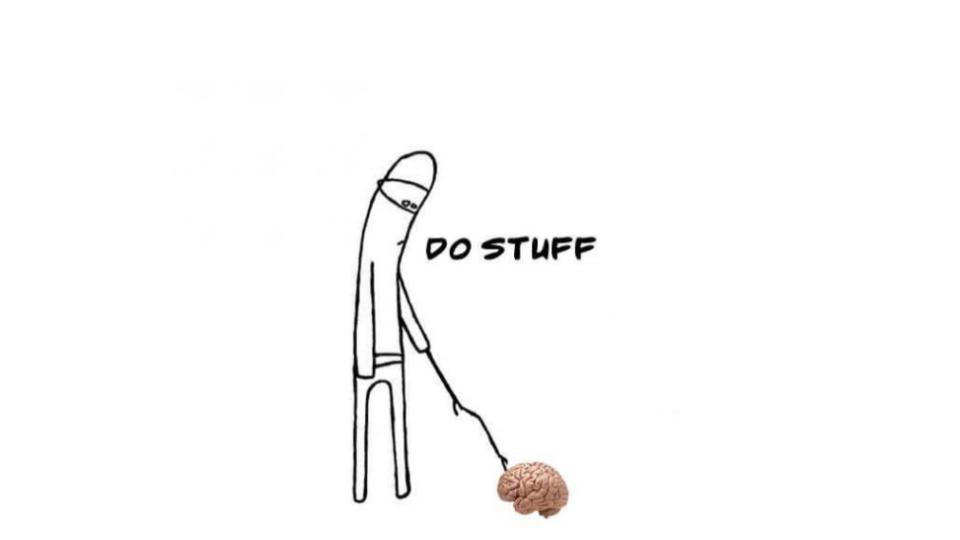

This is at least what Mercier and Sperber (2017) argue in The Enigma of Reason. But they are not making arguments about kneelers and chairs. They are arguing about our capacity to reason. Why do we reason? Why did the ability to reason evolve? What is it for? Their answer: we evolved the capacity to reason (i.e., to come up with reasons for defending certain beliefs and conclusions) so that we can win arguments. Let me say that again, because it really is a radical departure from many people's intuitions. The evolutionary function of reason is to win arguments.

Why would this be evolutionarily adaptive? Think of it this way. Throughout most of human history (i.e., the history of Homo sapiens), we have been fighting against the elements, against predators, and against other hominids—not to mention the invisible enemy of infectious disease. As it turns out, per Olshansky and Ault (1987), it is only in the 1800s that we became much more likely to die of degenerative diseases, such as heart disease and cancer, than infectious disease. Infectious disease, you know by now, requires the care of others. And so, whether you are fighting bad weather, running from predators, battling against a Neanderthal, or recovering from a viral infection, you need other people. Having good standing in your social group, in other words, is absolutely imperative to your survival. Put as a counterfactual, throughout most of our evolutionary history, to be without your group basically guaranteed an early death. Why is winning arguments relevant to keeping in good terms with your group? There's many reasons why a group might shun you. One of them might be your behavior. Just think of a falling out between friends because of something one of them did. What would be invaluable in a situation where you put your foot in your mouth or did something you shouldn't have is the capacity to explain yourself. That's where reason comes in. Any individuals who were able to explain themselves and spared themselves being banished from the group were more likely to survive, thus passing on their genes (along with their ability to win arguments).

Three things should be said here. First off, this is not the only socio-communicative theory of how reason evolved. Tomasello (2014) gives another theory (which is really cool). However, it looks like socio-communicative theories about the evolutionary function of reason, like those of Mercier and Sperber and Tomasello, are coming to be dominant. This kind of view is growing to be so convincing that, at the end of his A Natural History of Human Thinking, Tomasello makes the case that some socio-communicative theory must be true.

Second, what's so striking about this view is that it is so contrary to our typical conception of reason. We all seem to intuitively think that reason is for forming better beliefs. Right? Don't you think that your capacity to think rationally is there so that you can form more accurate beliefs and make better decisions? Apparently this is completely off. We happen to use reason in this way, sometimes at least. But reason isn't really for this intellectual function.

This brings me to the third point. Confirmation bias has been a specter that has been haunting us this entire course. We've noted repeatedly that it is an impediment for processing information accurately, for forming accurate beliefs, and for making optimal decisions. But now we finally understand why we have confirmation bias as part of our cognition. If the capacity to reason really were for some intellectual function, then confirmation bias seems to be a bug in our programming. It seems to stop us from performing our intellectual duties. But the capacity to reason isn't for some intellectual function; it's for winning arguments. In this context, confirmation bias makes perfect sense. When you're arguing (and your life's at stake), you really don't want to be engaging in an even-handed assessment of the situation. You (desperately) want to win. You want to be right. You need to be right. And in this context, confirmation bias isn't a bug: it's a feature. We've been assuming this whole time that our capacity to reason is a chair, but it's actually a kneeler.1

Argument Extraction

Know Your Enemy

After having thought about metacognition for a bit, it is perhaps a good idea to re-visit some arguments that we met early on in this course. In The Rule of the Knowledgeable we took a brief look at Caplan's (2008) book The Myth of the Rational Voter. The argument that Caplan makes isn’t about endorsing epistocracy, like that of Brennan (2017). Instead, he wants to dispose of the myth that voters are rationally ignorant. The idea behind rational ignorance is that voters do not stay current on political knowledge because the costs of acquiring political knowledge outweigh the benefits that the knowledge provides. In other words, if you believe in the rational ignorance hypothesis, you believe that a rational person would basically not bother with keeping up with politics because there's really no benefit to it.

Caplan disagrees with the rational ignorance hypothesis. He doesn't believe that voters are rationally ignorant. They're just plain ignorant. In other words, there is a difference between not keeping up with politics because you did a cost-benefit analysis and realized there's just no point and not knowing anything about politics and good policy (while sometimes pretending that you do). Caplan thinks most of the electorate is guilty of the second one of these. And he makes his case primarily by pointing out that there are large belief gaps between economics PhDs and the general public. Put differently, Caplan argues that the average voter would do miserably poorly in an introductory economics course and that, even if they were to take a course on economics, a single course wouldn't be enough to undo the systematic biases through which he/she views the world.

Notice your own thoughts on this matter right now. Some of you feel outrage. Some of you are already in agreement, without actually having read his book or hearing his argument. In fact, many of us instantly decide whether we agree with Caplan or not without really looking at the argument. I know people with PhDs that do this, by the way, so don't feel too bad. But at this point in this course, you should know that this is not path to good critical thinking.

Is Caplan right? I'm not sure. You'll have to read his book and decide for yourself. What I wanted to do primarily is get you thinking about your own thinking, your own reaction to an argument. It is only once you witness and accept the thoughts and feelings that naturally arise when coming face to face with a controversial viewpoint that you can begin to apply the principles of critical thinking we've been learning. So now that you've thought about your natural reaction to his writings, let's begin assessing Caplan's view. This will be woefully incomplete, by the way. A full analysis of this view belongs in a political science course. I just want to guide you through the first few steps.

Let's begin with the assumptions that fuel the argument. Caplan makes various assumptions during this book, but I will point out three here:

- If there is disagreement between the public and economics PhDs, then it is the public that is most likely wrong.

- Economics is the most important field to be knowledgeable about when making political decisions.

- Economics is monolithic, i.e., there is widespread agreement among economists about the right way to do economics, as well as agreement on what are the best policies for the economy.

Only when the assumptions are laid out in this way can we assess them for truth. So without further ado, here are some complications for Caplan and his assumptions...

Questioning Caplan's Assumptions

Economists' opinions are more accurate than non-economists?

First off, it’s important to note that nearly all of Caplan's case against rational ignorance relies on the belief gap between economics PhDs and the general public. Moreover, he admits that information on this matter is challenging to acquire. Ideally, you'd want a huge segment of the population to take some comprehensive economics tests, but no one is exactly volunteering for that. And so he essentially makes his case with data from only one study(!), albeit a large and well-crafted one (see Caplan 2008: 51-52). He also, I might add, claims that he’s following some assumptions made by Nobel prize winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman, namely an assumption about what counts as an error of judgment.

"The presence of an error of judgment is demonstrated by comparing people’s responses either with an established fact... or with an accepted rule of arithmetic, logic, or statistics” (Kahneman quoted in Caplan 2008: 52).

There are several criticisms that we can make at this point. First, economics is not an accepted rule of arithmetic, logic, or statistics. It is a social science and, like all social sciences (and really all science), its methods are continuously being updated and improved upon. He cannot and should not assume that what mainstream economists believe is some sort of fundamental law. This would actually be thoroughly unscientific, as we saw in the lesson titled...for the Stronger. So, Caplan pretends that he is using the definition of "error of judgment" from Kahneman. I understand why he wanted to pretend he was doing so. Who doesn't want to cite an Nobel prize winner to add a little prestige to their argument? But it appears that it is unjustified to even mention Kahneman here, since I believe Kahneman wouldn't agree with much of what Caplan claims.

Second, it is possible that the discipline of economics, at least its neoclassical wing (stay tuned), is heavily biased. That is to say neoclassical economists are mostly white and mostly male (see this recent newsletter). Now you might think to yourself, "So what?" Well, this is a problem because it is possible that the dominant theories that are being taught in neoclassical economics aren't being passed down because they are accurate or have a lot of predictive power; rather, they are being passed down because they appeal to white men. In fact, certain disciplines, take Political Science and Philosophy as two more examples, systematically alienate non-white, non-male students, since their dominant theories are not relevant to persons of color and women (see Mills 2017).

"The central debates in the field [of Political Science] as presented—aristocracy versus democracy, absolutism versus libertarianism, contractarianism versus communitarianism—exclude any reference to the modern global history of racism versus anti-racism, of abolitionist, anti-imperialist, anti-colonialist, anti-Jim Crow, anti-apartheid struggles... [Moreover]... The political history of the West is sanitized, reconstructed as if white racial domination and the oppression of people of color had not been central to that history" (Mills 2017: 33; emphasis added; interpolations are mine).

Because Political Science largely neglects how the (supposedly) universalist theories of thinkers like John Rawls and Immanuel Kant omit the history of white supremacy and patriarchy, and because neoclassical economics neglects the role that slavery had in overall American wealth and economic supremacy (see Beckert 2015), non-whites and non-males tend to steer clear of these disciplines. It's not interesting to them because it neglects their own experience and it doesn't teach them any actionable knowledge to guide their future actions. This creates an echo chamber where white males get to propagate theories that support their overall perspective. This obviously has a negative effect on the field, since the field is no longer aspiring to track the truth; instead it just propagates baseless theories that appeal to white men.

Now you might be saying, "That's just an accusation" and accusations are not enough to discredit a social science. Touché. However, it's not just an accusation. This brings me to my third point. Third, and most important, even relative to other social sciences, economics has recently come under heavy and persistent fire for its theoretical and empirical failings. Please enjoy the Food for Thought (and Sidebar!) below:

Given all this, we might be led to think that it's actually a good thing that the general population doesn't reliably think like a neoclassical economist. Of course, there is much more to this discussion. But(!) if you think this is a discussion that we need to have, then I've made my point: it's not clear that economists' opinions are more accurate than those of non-economists.

Is economics really the most politically relevant field?

There's many fields that might be more relevant to good governance than is economics, both in principle and in practice. Per my buddy Josh Casper, a majority of elected officials have a law degree (although it is unclear how many passed the bar). So, in practice, knowing the law is at least a good way of getting elected. One can also make the case that either International Affairs or Political Science is more relevant, at least with regards to theory. If one considers that it is important to know the effect of a policy on society's well-being and perspective, then Sociology and/or History might be some good candidates. Oh and by the way, since politicians spend most of their time fundraising, advertising or communications might be good disciplines for aspiring politicians—and I'm only saying this slightly tongue-in-cheek. Heck, even Philosophy might be a good idea; there's at least no sign that it leads to any more predictive failure than does neoclassical economics!

Is economics just neoclassical economics?

As we saw in the Food for thought, there are competing approaches in economics. In other words, neoclassical economics represents just one set of methods for the study of economics. Marxian economics and behavioral economics, for example, are two competing approaches, and they are steadily growing in their ranks. And there are other approaches still.2 Thus, Caplan can't pretend that there is unanimity among economists about what the best policies are. There's not even unanimity about the best way of doing economics!

- Read from 583b-592b (p. 284-296) of Republic.

- Start preparing for Quiz 3.7+.

Per linguist and developmental psychologist Michael Tomasello, the evolutionary origins of our capacity to reason are associated somehow with social communication. In other words, he makes the case that some socio-communicative theory of the evolutionary function of reason must be true.

One socio-communicative theory, by Mercier and Sperber, claims that we evolved the capacity to reason (i.e., to come up with reasons for defending certain beliefs and conclusions) so that we can win arguments and explain our behaviors to others.

Being aware of the like evolutinary origins of reason helps one understand one's own thought processes (metacognition) and why we are so riddled with confirmation bias.

In The Myth of the Rational Voter, economist Bryan Caplan makes three key assumptions when arguing that voters are plain ignorant. All three of those assumptions can be questioned.

FYI

Suggested Reading: Tom Stafford, How to get People to Overcome their Biases

TL;DR: Animated Lessons, Confirmation Bias: How to avoid it and make better decisions

Supplemental Material—

-

Video: VSauce, The Future of Reasoning

-

Audio: Philophy Bites Podcast, Dan Sperber on The Enigma of Reason

Related Material—

-

Reading: Richard Thaler, Integrating economics with psychology

-

Video: Richard Thaler, From Cashews to Nudges: The Evolution of Behavioral Economics

Advanced Material—

-

Reading: Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber, Why do humans reason? Arguments for an argumentative theory

Footnotes

1. Notice that if reason really is just for coming up with reasons that defend our behavior and beliefs, then this suggests that it is separate from the part of our brain that actually determines our behavior and beliefs. At least this is what the neuroscientists Michael Gazzaniga concluded. After studying split-brain patients his entire career, he arrived at the view that our actions are decided on by one part of the brain, while our justifications for our actions are invented by a different part. He calls the part of our brain that justifies our actions/beliefs (once they’ve already been decided on by another part of the brain) the interpreter module (see Gazzaniga 2012). By the way, in The Blank Slate, cognitive scientist Steven Pinker refers to the interpreter module by a less flattering name: the baloney generator.

2. Click here for an interview with Manfred Max-Neef about his “barefoot economics.”