Problems/Solutions

The past is a foreign country;

they do things differently there.

~L.P. Hartley

Philosophy is dead

Teaching an introductory course in philosophy requires more assumptions than this instructor is comfortable with. First off, you have to (at least provisionally) demarcate, or set some boundaries, regarding what philosophy is and what philosophy isn't. Unfortunately for this instructor, however, philosophy has been different things at different times and different places.

For example, in classical Greece, it is difficult to distinguish philosophy from what today we would call the beginnings of natural science. Is philosophy the same as science, then? I think we can all agree that that's definitely not the case. But there is a bit of philosophy in science. Allow me to clarify.

The origins of natural science come from multiple, sometimes unexpected, origins, many of them going back to ancient Greece. For example, Freeman (2003: 7-25) discusses the competitive nature of Greek debate and the rejection of supernatural explanations by philosophers, beginning with Thales of Miletus. This competitiveness and rejection of non-natural causes are obviously an important part of what would eventually become science. But, and this is important, it's not the whole picture.

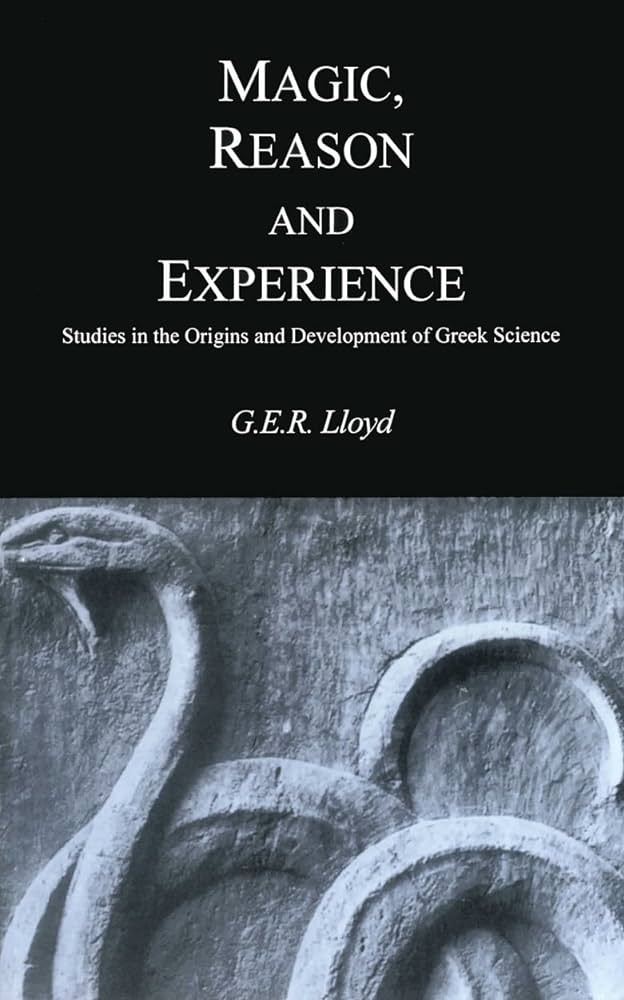

Here's another important ingredient. Chapter 4 of G.E.R. Lloyd's (1999) Magic, Reason, and Experience makes the case that practices in political debate made their way into the study of the natural world too. He shows how the Greek word for witness was the root of the word for evidence (specifically in scientific discourse). He also shows that the word for cross-examination of a witness is related to the language behind the testing of a hypothesis. So aspects of the legal tradition from Greece made their way into the study of nature.

We often times want simple and intuitive explanations, but the complexity of the world does not allow for that. And so we should understand the origins of complex institutions to be multifactorial, and we should expect that the essential ingredients of complex institutions are sometimes spread thinly across time. The origins of natural science are, in fact, extremely variegated. There are some elements of science that came about in ancient Greece, yes. But there are some elements of science that were not fully formed until the early modern era, from about 1500-1800 CE. Other elements had to wait longer still before they were fully codified; this is something that we will see in this course.

And so, I would never for a second want to suggest that philosophy single-handedly gave birth to science; but I will say that it was there during its conception, it was present during science's long gestation period, and it played a non-negligible role in its birth. And yet, this doesn't get us any closer to defining philosophy, and anyone who is tasked with teaching it still has a problem on their hands.

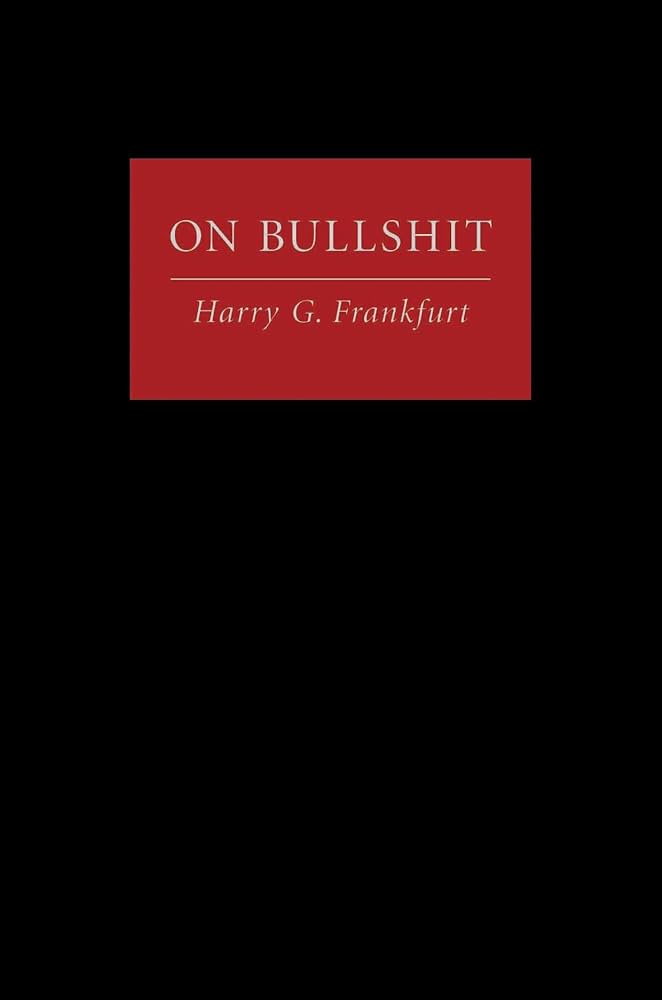

Here's another problem that arises if someone is trying to teach an introductory course in philosophy: many are predisposed to think of philosophy as bullshit. Bullshit, by the way, is actually a technical term in philosophy. I'm not kidding. Harry Frankfurt (2009; originally published in 2005) argues that bullshit (a comment made to persuade, regardless of the truth) has been on the rise for the last several decades. How do you know a bullshitter? “The liar cares about the truth and attempts to hide it; the bullshitter doesn't care if what they say is true or false, but rather only cares whether or not their listener is persuaded” (ibid., 61).

Students/colleagues who instinctively think little of philosophy don't usually come out and say the word "bullshit", but it lurks somewhere in their minds. To be honest, I don't completely disagree with them. Some philosophy is bullshit. In fact, in a follow-up to Frankfurt's 2005 monograph, Oxford philosopher G. A. Cohen charges that Frankfurt overlooked a whole category of bullshit: the kind that appears in academic works. Cohen argues that some thinkers write in ways that are not only unclear but also unclarifiable. In Cohen's second definition, which applies to the academy, bullshit is the obscure that cannot be rendered unobscure. And so, there is bullshit in philosophy, because there are (unfortunately) some philosophers who write/wrote in a completely unintelligible way. It sounds like word salad to yours truly. They were completely indifferent to having precision in meaning, and this is exceedingly regrettable for the discipline (see Sokal and Bricmont 1999). In fact, we're still trying to get past that caricature of what philosophy is.

But here's where the problem lies. It's not all bullshit. If you argue that much of philosophy is unnecessarily obscure and even pointless, consider me an ally. But if you think no philosophy is or has ever been worthwhile, then you have another thing coming.

This latter objection to philosophy, the notion that no philosophy is or has ever been worthwhile, is (I think) symptomatic of a profound anti-intellectualism that we find in our society. I'm sure you've met people that don't recognize when their beliefs are inconsistent (or self-contradictory). Perhaps you've met people who believe in completely incoherent conspiracy theories about new world orders, vaccines, and/or reptilian aliens. I've certainly met people who proudly claim that they read no books but the Bible, which (alarmingly) they believe to have been originally written in English (which is literally not possible). This, and I hope you share my sentiments, is not okay.

Decoding Philosophy

Sidebar

I actually have a theory as to why some people instinctually dislike philosophy. It has to do with something called the halo effect. First, take a look at the Cognitive Bias of the Day below.

Cognitive Bias of the Day

The halo effect, first posited by Thorndike (1920), is our tendency to, once we’ve positively assessed one aspect of a person (or brand, company, product, etc.) to also positively assess other unrelated aspects of that same entity (see also Nisbett and Wilson 1977 and Rosenzweig 2014).

Rosenzweig's analysis of this bias is particularly enlightening. He shows that this bias is rampant in the business world. Consider Company X. Let me first tell you that Company X has had record bonuses for higher management two years in a row. Now let me ask you a question: Do you think that management at Company X is exceptionally good? In order to make a truly educated guess, you'd have to look at more than the bonuses of the executives. You'd have to also look at retention rate, overall profits, how competitors are doing, etc. But the mind naturally wants to say, "Yes! There must be good management there, because why else would there be record bonuses for high management!" This is the halo effect at work, and if you don't pay attention to how this bias influences your assessments of firms and market behavior, then you are going to make mistakes that will cost you money.

How does this explain why philosophy is looked down upon? My general sense is that, prior to a college introductory course, most students know very little or nothing about philosophy. The reasons for this are complicated, as stated above, but suffice it to say that people don't know how to feel about this discipline. Hence, the mind feels uneasiness about this subject. Uneasiness is not something that the human mind is built to endure. We naturally look for resolutions to any kind of cognitive dissonance (see Tavris and Aronson 2020). And so, when faced with a discipline we've never been exposed to before, we think to ourselves, "Had this subject been worth a damn, I would've already known about it." And so, this dissonance is resolved by deciding that the subject isn't really worthwhile.

It could also be the case that as students are choosing their majors, they lack deep and substantive reasons for choosing said majors. After all, they don't know much about the field yet. And so, some feel the need to denigrate other disciplines so as to ease cognitive dissonance. In other words, they feel a need to have good reasons for why they chose their discipline, they don't have them, and so they construct reasons why other disciplines "suck." The general idea is that the mind is doing something like this, "My discipline [which I don't know much about yet] is way better than these other disciplines since [insert whatever I can think of in the moment]."

That's at least part of my theory...

Solutions

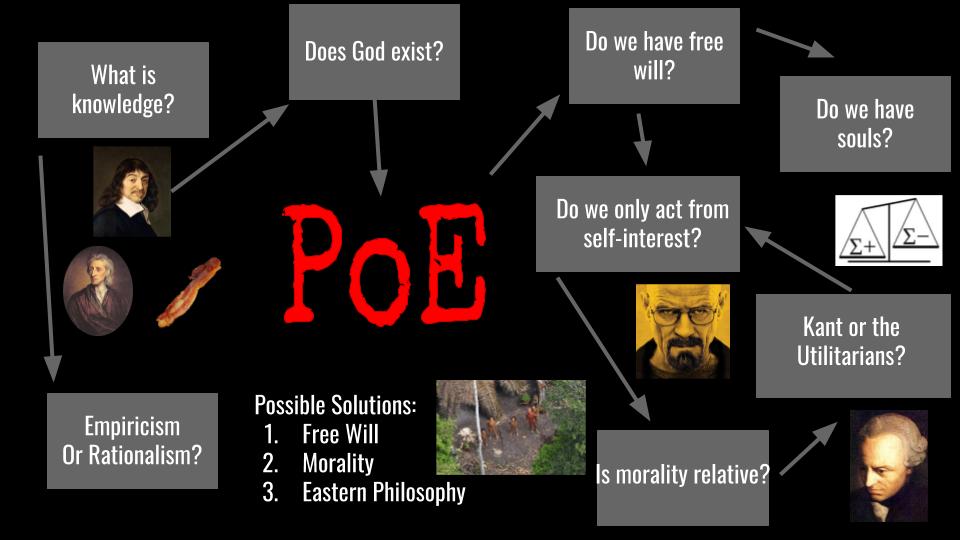

None of the preceding, by the way, even remotely solves our demarcation problem, the setting of boundaries between what counts as philosophy and what doesn't. A standard "solution" to this problem is to use a question-based approach in introductory classes. In other words, the idea is to pose questions that are traditionally accepted as being philosophical, whatever that may mean, and look at the responses of professional philosophers. This is, more or less, the approach that I will take. However, I will not limit myself to philosophers. Being a voracious reader, I am able to add the input of thinkers from various disciplines to this conversation. As such, I will pose questions that are traditionally accepted as being philosophical and look at the responses of conventional philosophers (in a historical context) as well as the responses of psychologists, neuroscientists, mathematicians, and anyone else who might have something relevant to say.

Frankly, though, this instructor doesn't want to waste your time. To me, it wasn't enough to just cover traditional philosophical questions. So instead, I've decided to build a course that tells a story—actually, a history. I'm going to teach you a history that I think is worth knowing. It's not necessarily a history of philosophy. In a way, in fact, the philosophy is incidental. But don't worry. There'll be plenty of mind-bending philosophical ideas, and I'm bound to upset a few individuals (if I haven't already). Nonetheless, I think it's a story worth telling.

Collapse

The story that will be told in this course is, in a way, about collapse. If we are taking this negative perspective, we will be looking at how ideas can "collapse". But this is much too vague, especially after going on a tirade against some bullshit philosophers above. Let me begin with a more concrete example of collapse. Please enjoy your first Storytime! of this course:

It is difficult to imagine that our own civilization could collapse. It is even harder to imagine that our civilization could collapse and that humans centuries from now—if we still exist—would have no idea how our gadgets and technologies were made (although perhaps this is easier to imagine post-COVID). And yet, we know from the historical record that civilization has its highs and lows. At one point, Rome was the most splendid city in the world. Still it fell (and tragically so). In fact, historian Ian Morris called the fall of the Roman Empire the single greatest regression in human history.

We can speculate as to why it's difficult to think of our collapse in any realistic way. We do seem to have an end of history illusion. This is the bias that makes us believe that we are, for all intents and purposes, done "growing". We believe that our experiences have resulted in a set of personal tastes and preferences which will not substantially change in the future. We pretty much believe we're "done". This is, of course, not true at all, but other biases come in to block us from realizing this. The recall bias, for example, does not allow us to remember previous events or experiences accurately, especially if they conflict with input we are actively receiving. So, if your preferences did change, you are likely to think you've always held those preferences and not even notice the change.2

And so maybe these biases are active not only in our assessments about ourselves, but also in how we view history itself. Perhaps we have a predisposition to thinking that history is "done". We're "it". Civilizational complexity won't dip any lower than we are, and it won't rise much higher either.

But reason compels us to dive deeper. I don't have to remind you that civilizational collapse is a real threat. Global warming, nuclear weapons, superintelligent artificial intelligence, and other existential risks might change your life dramatically. Rest assured: The world will change; the only question is whether it will change through wisdom or through catastrophe.

This is the nature of collapse. It's the flipside of progress, it seems. And just like civilizations can rise and fall, so can ideas. In fact, ideas are sometimes a causal actor in the collapse of some civilizations (Freeman 2003). In this class, we'll look at one such collapse.

Important Concepts

I've taken the liberty of isolating most of the important concepts in each lesson and giving them their own section. Please take a moment to review the concepts below.

Some comments

Although in an introductory philosophy class you will not dive deep into the nature of logical consistency, since that is reserved for a course in introductory logic, I believe that you intuitively (and non-consciously) care about logical consistency. If you've ever seen a movie with a plothole and it bothered you, then you care about logical consistency. It's just that simple. Consistency just means that the sentences describing the event in the movie can all be true at the same time. But in plotholes, this is not possible. Some parts of the movie contradict other parts. And so, the movie contains inconsistencies and we intuitively sense something is wrong.

Logical consistency will be a cornerstone of everything we will be doing. We will build up conceptual frameworks (i.e., philosophical theories) and we will be perpetually on the lookout to ensure that the ideas in question do not contradict each other. As such, it is important that you understand this concept well. Logical consistency only means that it's possible that all the sentences in a set are true at the same time. That's it. Don't equate consistency with truth. Two statements can be consistent while being false. For example, here are two sentences.

- "The present King of France is bald."

- "Baldness is inherited from your mother's side of the family."

"The present King of France is bald" is false. This is because there is no king of France. Nonetheless, these sentences are logically consistent. They can both be true at the same time, it just happens that they're not both true.3

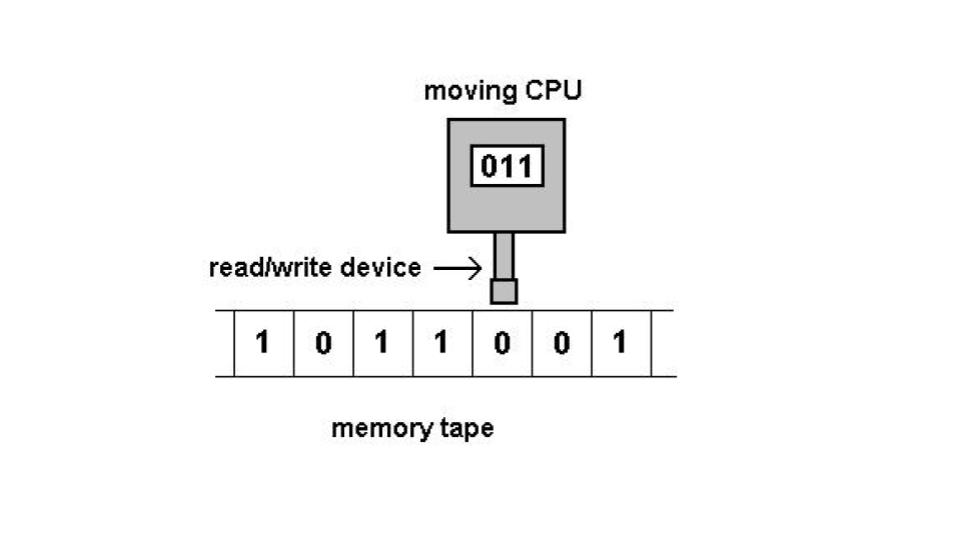

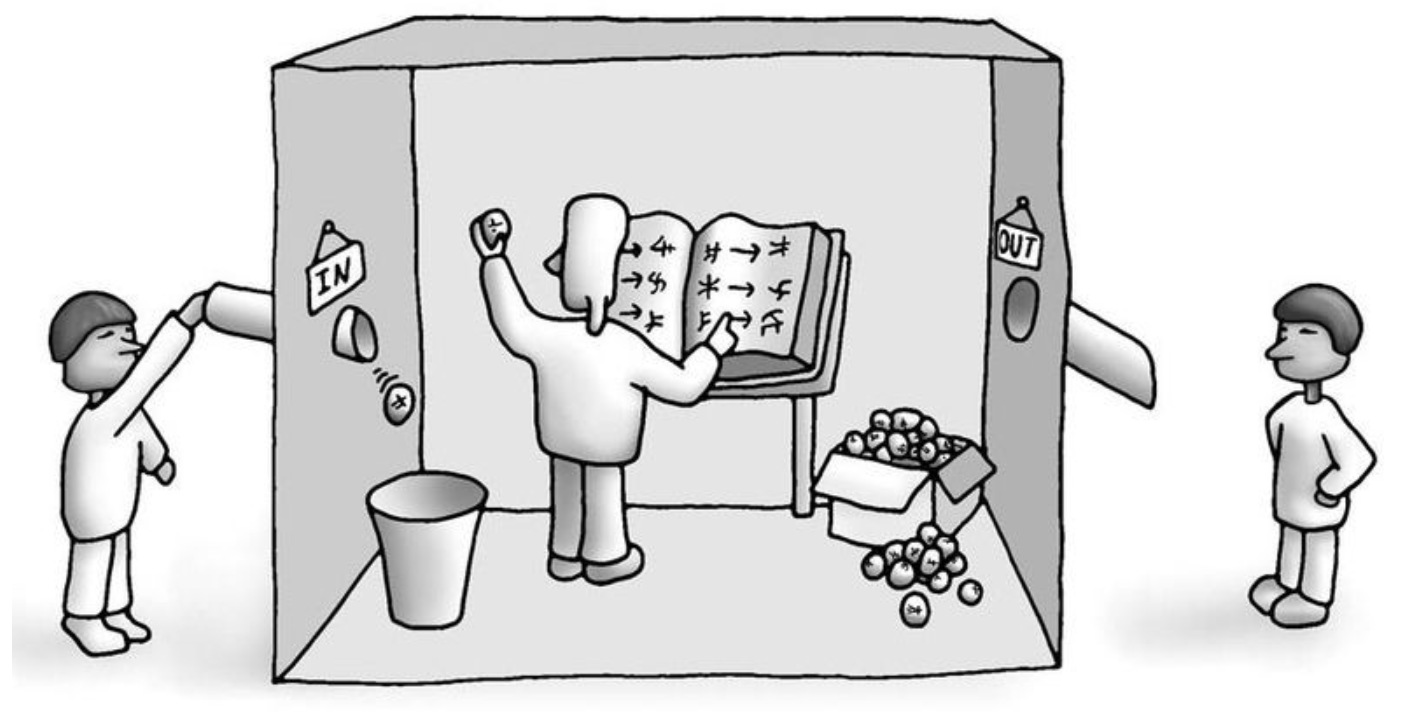

Arguments will also be central to this class. Arguments in this class, however, will not be heated exchanges like the kind that couples have in the middle of an IKEA showroom. For philosophers, arguments are just piles of sentences that are meant to support another sentence, i.e., the conclusion. The language of arguments has been co-opted into other disciplines, such as computer science, but, although I'll cover this briefly, you'll have to learn about that mostly in a logic or computer science course.

Food for Thought...

Informal Fallacy of the Day

As you learned in the Important Concepts, there are two types of fallacies: formal and informal. A course in symbolic logic focuses on formal reasoning through the use of a specialized language. Formal fallacies are most clearly understood in this context. We won't be covering them here. There are also classes that focus more on the informal aspect of argumentation, such as PHIL 105: Critical Thinking and Discourse. Typically all the informal fallacies are covered in courses like these. In our case, we will only infrequently discuss some informal fallacies. Here's your first one!

Eurocentrism

On multiple occasions, well-meaning colleagues have questioned why I don't feature some non-Western philosophies in my introductory courses. Even some students have asked me about this. I'd like to now give you a summary of the reasons I have for focusing mostly on the Western Tradition in PHIL 101.

Three Reasons Why I Focus on the Western Tradition in PHIL 101

Although my friends and colleagues are well-meaning, there is a hint of a potentially pernicious implication in their line of questioning. It almost seems like they are asking, "Why don't you focus on material that is more yours?" The implication is that neither I, nor my students of non-European descent, are really Western. I hate to be the bearer of bad news, but Europeans (and the descendants of Europeans) have dominated much of the world since the middle of the 20th century, whether it be culturally, economically, politically, or militarily (as in the numerous American occupations after World War II). It's also true that European standards (of reasoning, of measuring, of monetary value, etc.) have become predominant in the world as part of a general (if accidental) imperial project (see chapter 21 of Immerwahr's 2019 How to Hide an Empire). Thus, those of us who are Latinx, Native American, of African descent, etc., are immersed in Western culture, whether we like it or not. It is our right to learn about Western culture, because it has become our culture, even if it was through conquest (or worse). It is our duty as good thinkers, however, to also be critical of this tradition, which is how we will progress.

Moreover, as I think you will come to see, whether you are of European descent or not, Western ideas really do permeate your mind. I believe this because students that should, according to my well-meaning colleagues, be more closely aligned with a non-Western ideology actually become very defensive when I question Western ideas. As we go through this class, you will notice that some of your most deeply held convictions are Western in origin. And it's going to bother you when I go after them. Fun times ahead.

The Europeans who gave rise to the Western tradition had some really good ideas! I'm not going to not cover them just to assuage white guilt. These great ideas include, by the way, democratic governance, classical liberalism, humanism, and the modern scientific method. We must give credit where credit is due.

The Europeans who gave rise to the Western tradition also had some really bad ideas, and I want to cover them. But it is unfair, I think, to look at only the bad. In order to assess a tradition, we must approach it from all directions. I will tell you about the good and the bad. And if there's one thing you should know about yours truly it's that I don't pull punches. This will be, without a doubt, a critical introduction.

I promise I'll try to give you an even-handed assessment of this tradition. Know that I'm doing it this way because I don't want us to fall into the traps laid on us by our biases, from the halo effect to the end-of-history illusion. We can't just say, "Philosophy bad" or "Yay non-Western philosophy". The world is nuanced. Ideas are nuanced. In the days to come, you'll have to fight your urge to either completely accept or completely reject an idea. It's time to be ok with cognitive discomfort.

One last thing...

I designed this course so that it all revolves ultimately around one simple question. It may seem unlikely, but every single topic we'll be covering will, in the final analysis, be connected to this question. As such, I call this the fundamental question of the course. Stay tuned.

Anyone tasked with teaching introductory is faced with two problems: demarcating what philosophy actually is (and then teaching it), and overcoming the initial apprehension that some have about the discipline.

The main theme of the course is, depressingly(?), collapse. We will study the collapse of an idea.

The notion of logical consistency and the analysis of rational argumentation will play essential roles throughout the course.

The influence of the Western Tradition is pervasive. You will find that many ideas that are traditionally considered to be "Western" reside within your mind, whether you are of European descent or not.

Lifestyle Upgrade

As we learned in today's lesson, what philosophy is varies between time periods and even thinkers within certain time periods. In these sections, I'd like to focus on philosophy as a way of life, the so-called lifestyle philosophies of, for example, the Stoics. The Stoics, above all else, sought to live life in accordance with nature. For them, this meant living wisely and virtuously. This was done by using reason to help them achieve excellence of character: presence of mind, wisdom, understanding reality as it truly is, not letting emotions get the better of them, and the development of generally desirable character traits.

What can we do in this course that is Stoic-approved? Well, in your current role, your task is to learn this material. So, a Stoic would emphasize dedicating yourself to fulfilling your duties.

How does one learn material like this? As it turns out, most students are completely new to the discipline of philosophy, since it is not taught at the high school level usually. This means you're not always sure how to go about studying. So, in what follows, I hope to make some recommendations that you can implement during the rest of this course.

To learn philosophy, you need to engage in both declarative and procedural learning. You might not know what that means, and that's ok, so let me just tell you what to do. First off, the first step is to learn the relevant concepts. Before really diving into a lesson, you should skim it and look for all the concepts that are underlined, bolded, or that otherwise seem important. (In the next lesson, they are as follows: deduction (deductive arguments), induction (inductive arguments), validity, soundness, imagination method, modus ponens, modus tollens, epistemology, metaphysics, JTB theory of knowledge, skepticism, the regress argument, and begging the question.) Write them down and define them using the content in the lesson. Practice these words for a bit. Read the name of the concept, cover up the definition, and try to recall what it is that you wrote. This is called retrieval practice. Once you do this a few times, take a break. After a five minute break or so, you're ready to read the lesson.

As you're reading the lesson take careful notes on the topic that is being argued, what is being argued (i.e., the different positions on the topic), and what the arguments for and against these views are. This might take a while. I recommend you do this in 25-minute "bursts". Set a timer, put away all distractions (like phones), and start to work through the material. Once the timer goes off, take a break. Then repeat until you complete the lesson.

All these recommendations, by the way, come from the most up-to-date findings in educational neuroscience and should work for any class. You can check out A Mind for Numbers, How We Learn, and Uncommon Sense Teaching for more info on this. If you don't time to read these at the moment, here's a TEDTalk by the author of A Mind for Numbers and co-author of Uncommon Sense Teaching, Barbara Oakley:

I'll give you some more tips next time. Until then, remember that your mind is the most fundamental tool you have in life. All other tools are only utilized well once you have mastered your own mind. Training and taking control of your mind is, in a sense, literally everything.

FYI

Supplemental Material—

- Video: School of Life, What is Philosophy for?

-

Philosophy Bites, What is Philosophy?

-

Reading: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Entry on Fallacies

-

Note: Most relevant to the class are Sections 1 & 2, but sections 3 & 4 are very interesting.

-

-

Text Supplement: Useful List of Fallacies

Footnotes

1. For an introduction to the history and philosophy of science, DeWitt (2018) is definitely a good start.

2. An interesting example of the recall bias can be found in breast cancer patients. Apparently, getting diagnosed with breast cancer changes a woman's retrospective assessment of her eating habits. In particular, it makes patients more likely to remember eating high-fat foods, as compared to women who were not diagnosed with breast cancer. This is the case even in longitudinal studies where records of the subjects' food diaries suggest no discernible difference in eating patterns between the two groups. It is simply the case that cancer patients believe they ate more high-fat foods because they are sick. It is the reality of being faced with a deadly cancer (an active input) that predisposes their minds towards remembering actions and events that might've led to this sickly state, whether they actually happened or not (see Wheelan 2013, chapter 6).

3. Contrary to popular belief, apparently baldness is not all your mother's fault. In the very least, smoking and drinking have an effect.

Agrippa's Trilemma

Not to know what happened before you were born is to remain forever a child.

~Cicero

On the possibility of the impossibility of learning from history

There are so many cognitive traps when one is studying history. As we mentioned last time, we have biases operating at an unconscious level that don't allow us to perform an even-handed assessment of persons, ideas, products, etc. These biases might also disallow us from properly assessing a culture from the past (or even a contemporary culture that is very different from our own). In addition to this, however, it appears that we sapiens are surprisingly malleable with regards to the tastes and preferences that culture can bestow in us. Cultures, past and present, range widely on matters regarding humor, the family, art, when shame is appropriate, when anger is appropriate, alcohol, drugs, sex, rituals at time of death, and so much more.1

Recognizing our limitations, we have to always be cognizant of the boundaries of our intuition and of our prejudices. More than anything, we need to keep in check our unconscious desire to want to know how to feel about something right away. Whether it be some person, some practice, some event, or some idea, our mind does not like dealing in ambiguities; it wants to know how to feel right away.

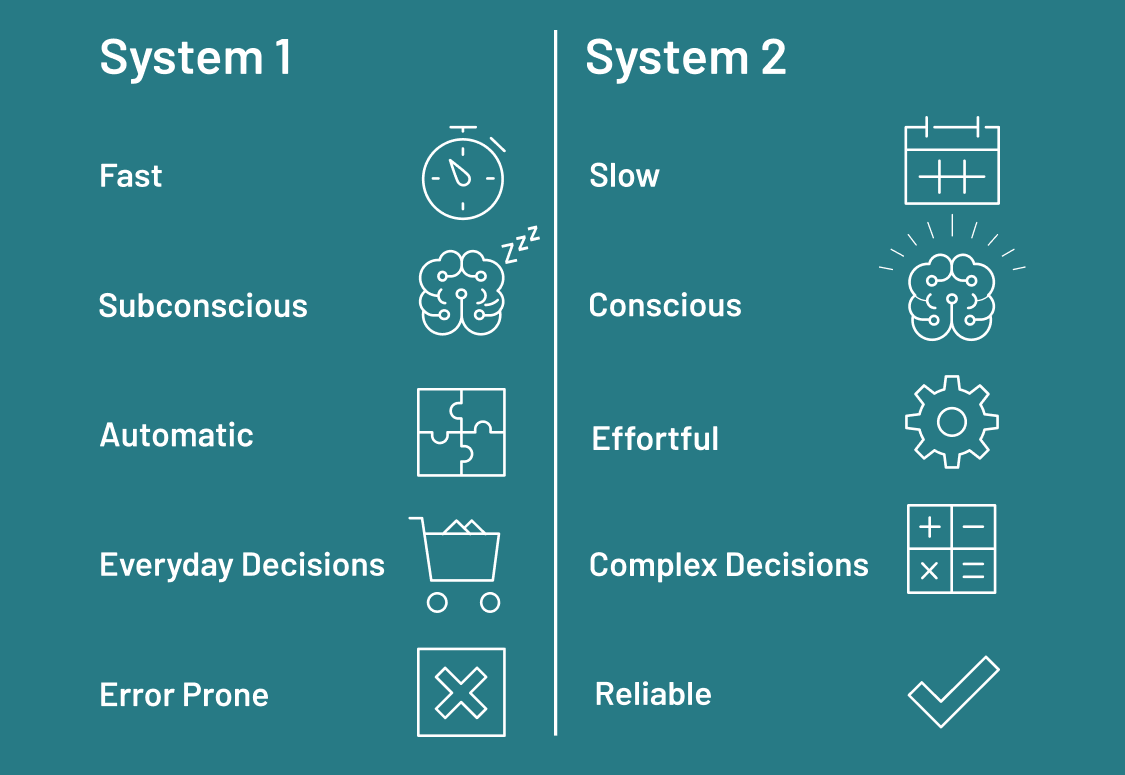

The psychological machinery that underlies all this is very interesting. The psychological model endorsed by Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman, known as dual-process theory, is illuminating on this topic. Although I cannot give a proper summary of his view here, the gist is this. We have two mental systems that operate in concert: a fast, automatic one (System 1) and a slow one that requires cognitive effort to use (System 2). Most of the time, System 1 is in control. You go about your day making rapid, automatic inferences about social behavior, small talk, and the like. System 2 operates in the domain of doubt and uncertainty. You'll know System 2 is activated when you are exerting cognitive effort. This is the type of deliberate reasoning that occurs when you are learning a new skill, doing a complicated math problem, making difficult life choices, etc.2

How is this related to the study of history? Here is what I'm thinking. It appears that cognitive ease, a mental feeling that occurs when inferences are made fluently and without effort (i.e., when System 1 is in charge) makes you more likely to accept a premise (i.e., to be persuaded). In fact, it's been shown that using easy-to-understand words increases your capacity to persuade (Oppenheimer 2006). On the flip side, cognitive strain increases critical rigor. For example, in one study, researchers displayed word problems with bad font, thereby causing cognitive strain in subjects (since one has to strain to see the problem). Fascinatingly, this actually improved their performance(!). This is due to the cessation of cognitive ease and the increase of cognitive strain, which kicked System 2 in to gear (Alter et al. 2007).

It is even the case that cognitive ease is associated with good feelings. When researchers made it so that images are more easily recognizable to subjects (by displaying the outline of the object just before the object itself was displayed), they were able to detect electrical impulses from the facial muscles that are utilized during smiling (Winkielman and Cacioppo 2001).3

The long and short of it is that if you are in a state of cognitive ease, you'll be less critical; if you are in a state of cognitive strain, you've activated System 2 and you are more likely to be critical.

Thus, when you hear or read about cultural practices that are very much like your own, you often unquestioningly accept them, since you are in a state of cognitive ease. However, when you read about cultural practices (or ideas or whatever) that are very much unlike your own, this increases cognitive strain. Because of this, we are more likely to be critical about such practices (or ideas, etc.). Of course, it is ok to be critical, but we are often overly critical, applying a strict standard that we don't apply to our own culture. Moreover, this is compounded by the halo effect. We've found one thing we don't like about said culture, and so we erroneously infer the whole culture is rotten.

I'm not, of course, saying that this effect manifests itself in everyone all the time, or even in some people all the time. But it is a possible cognitive roadblock that might arise when you are going through the intellectual history that we'll be going through.

High-water mark

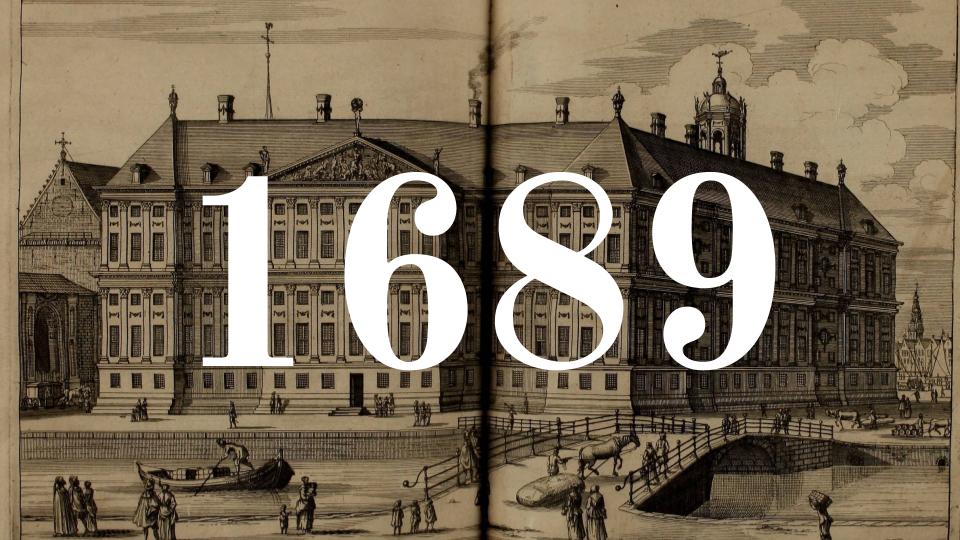

We'll begin our story soon, but let me give you two bits of historical context. The first has to do with the recent memory of the characters in our story. We will begin our story next time in the year 1600, but to begin to understand why the thinkers we are covering thought the way they did, you have to first know what they had seen, what their parents had seen, what they had been raised to accept. The 16th and early 17th centuries were, in my assessment, the high-water mark of religiosity in Europe. This period was characterized by a religious conviction that is only rivaled, to my mind, by the brief period of Christian persecution at the hands of the Romans under Nero.4

I am not alone in believing that this period stands out. In their social history of logic, Shenefelt and White (2013: 125-130) discuss the religious fanaticism of the 16th and 17th centuries, which are stained with wars of religion. The wars of this time period included the German Peasant Rebellion in 1524 (shortly after Martin Luther posted his Ninety-five Theses in 1517), the Münster Rebellion of 1534-1535, the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre (1572), and the pervasive fighting between Catholics and Protestants that culminated in the Thirty Years War (1618-1648). Shenefelt and White also discuss how these events inspired some thinkers to argue that beliefs needed to be supported by more than just faith and dogma. Thinkers became increasingly convinced that our beliefs require strong foundations. My guess is that if you lived through those times, you would've likely been in shock too. You would've longed for a way to restore order.

And so this is why I call this the high-water mark of religiosity. But notice that embedded in this claim is a very improper implication. By saying that this was the highest point of religious fervor in the West, and by grouping (most of) you into the greater Western tradition, I'm implying that these 16th and 17th century believers were more religious than you are (if you are religious). How very devious of me! Notwithstanding the outrage that many have expressed when I say this, I stand by my claim. It really does seem to me that the religious commitment of 16th and 17th century Christians was stronger than that of Christians today.

At this point, we could get into a debate about what religious commitment really is; or how the institution that one is committed to might change over the centuries so that commitment looks different in different time periods. I'd love to have those conversations. My general argument would be that the standards of what it meant to be a believer back then were higher than the standards of today (where going to a service once a week suffices for many). But without even getting deep into that, let's just look at the behavior of believers 400 years ago. Maybe once you learn about some of their practices, you'll side with me.

When I first wrote this lesson, I knew I needed something shocking to show you just how different things were in the early modern period in Europe. And, to be honest, I didn't think for too long. I knew right away what would drop your jaw. I'm going to describe for you an execution, in blood-curdling detail—an execution steeped in religious symbolism and where the "audience" was sometimes jealous of the person being tortured and executed.

Stay tuned.

Important Concepts

Distinguishing Deduction and Induction

As you saw in the Important Concepts, I distinguish deduction and induction thus: deduction purports to establish the certainty of the conclusion while induction establishes only that the conclusion is probable.5 So basically, deduction gives you certainty, induction gives you probabilistic conclusions. If you perform an internet search, however, this is not always what you'll find. Some websites define deduction as going from general statements to particular ones, and induction is defined as going from particular statements to general ones. I understand this way of framing the two, but this distinction isn't foolproof. For example, you can write an inductive argument that goes from general principles to particular ones, like only deduction is supposed to do:

- Generally speaking, criminals return to the scene of the crime.

- Generally speaking, fingerprints have only one likely match.

- Thus, since Sam was seen at the scene of the crime and his prints matched, he is likely the culprit.

I know that I really emphasized the general aspect of the premises, and I also know that those statements are debatable. But what isn't debatable is that the conclusion is not certain. It only has a high degree of probability of being true. As such, using my distinction, it is an inductive argument. But clearly we arrived at this conclusion (a particular statement about one guy) from general statements (about the general tendencies of criminals and the general accuracy of fingerprint investigations). All this to say that for this course, we'll be exclusively using the distinction established in the Important Concepts: deduction gives you certainty, induction gives you probability.

In reality, this distinction between deduction and induction is fuzzier than you might think. In fact, recently (historically speaking), Axelrod (1997: 3-4) argues that agent-based models, a new fangled computer modeling approach to solving problems in the social and biological sciences, is a third form of reasoning, neither inductive nor deductive. As you can tell, this story gets complicated, but it's a discussion that belongs in a course on Argument Theory.

Food for Thought...

Alas...

In this course we will only focus on deductive reasoning, due to the particular thinkers we are covering and their preference for deductive certainty. Inductive logic is a whole course unto itself. In fact, it's more like a whole set of courses. I might add that inductive reasoning might be important to learn if you are pursuing a career in computer science. This is because there is a clear analogy between statistics (a form of inductive reasoning) and machine learning (see Dangeti 2017). Nonetheless, this will be one of the few times we discuss induction. What will be important to know for our purposes, at least for now, is only the basic distinction between the two forms of reasoning.

Assessing Arguments

Some comments

Validity and soundness are the jargon of deduction. Induction has it's own language of assessment, which we will not cover. These concepts will be with us through the end of the course, so let's make sure we understand them. When first learning the concepts of validity and soundness students often fail to recognize that validity is a concept that is independent of truth. Validity merely means that if the premises are true, the conclusion must be true. So once you've decided that an argument is valid, a necessary first step in the assessment of arguments, then you proceed to assess each individual premise for truth. If all the premises are true, then we can further brand the argument as sound.6 If an argument has achieved this status, then a rational person would accept the conclusion.

Let's take a look at some examples. Here's an argument:

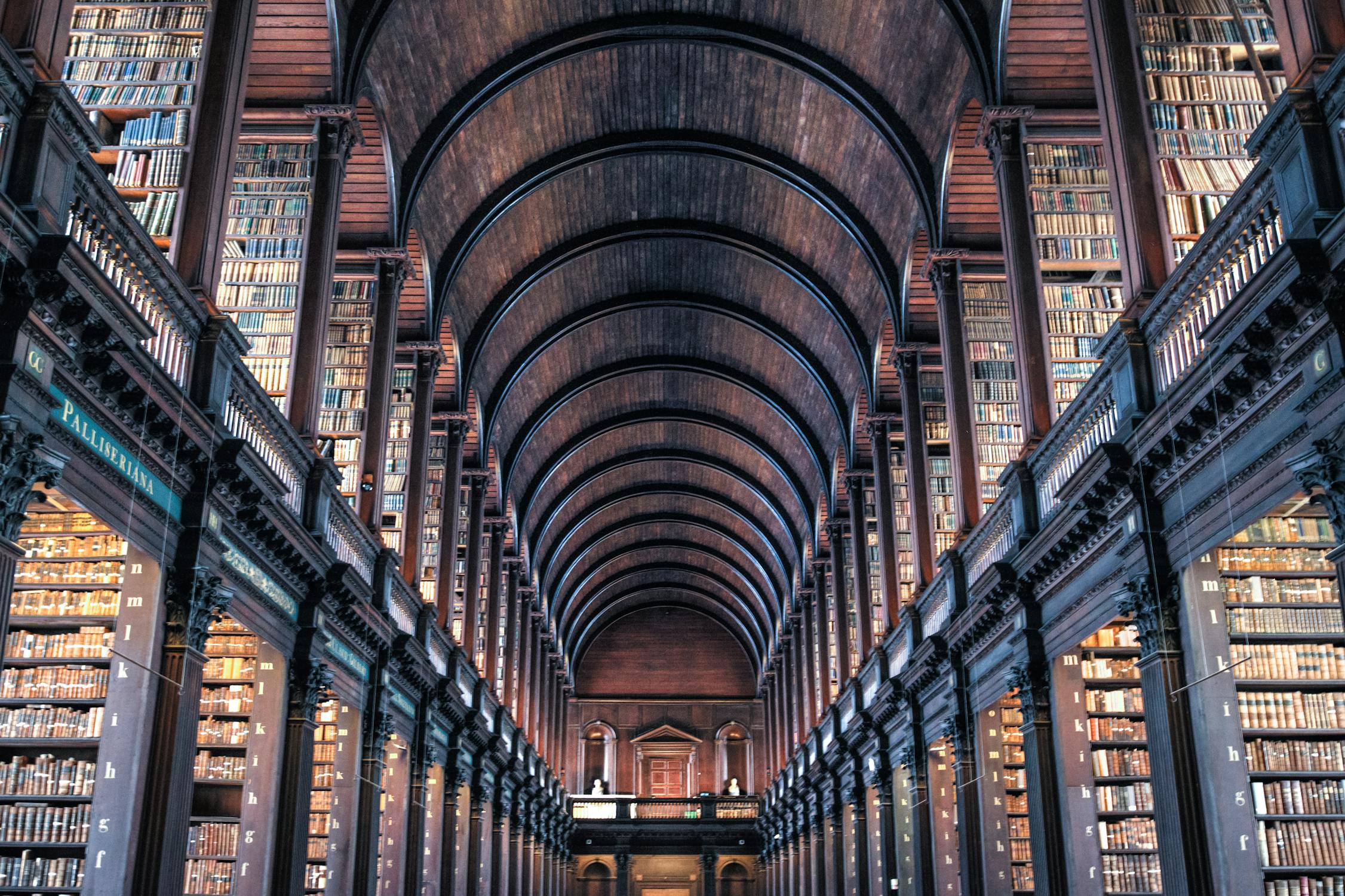

- Every painting ever made is in The Library of Babel.

- “La Persistencia de la Memoria” is a painting by Salvador Dalí.

- Therefore, “La Persistencia de la Memoria” is in The Library of Babel.

At first glance, some people immediately sense something wrong about this argument, but it is important to specify what is amiss. Let's first assess for validity. If the premises are true, does the conclusion have to be true? Think about it. The answer is yes. If every painting ever is in this library and "La Persistencia de la Memoria" is a painting, then this painting should be housed in this library. So the argument is valid.

But validity is cheap. Anyone who can arrange sentences in the right way can engineer a valid argument. Soundness is what counts. Now that we've assessed the argument as valid, let's assess it for soundness. Are the premises actually true? The answer is: no. The second premise is true (see the image below). However, there is no such thing as the Library of Babel; it is a fiction invented by a poet. So, the argument is not sound. You are not rationally required to believe it.

Here's one more:

- All lawyers are liars.

- Jim is a lawyer.

- Therefore Jim is a liar.

You try it!7

Pattern Recognition

The second bit

I said we needed two bits of historical context before proceeding. I gave you one: the high-water mark of religiosity. Here's the other.

In 1600, the Aristotelian view of science still dominated. Intellectuals of the age saw themselves as connected to the ancient ideas of Greek and Roman philosophers. It's even the case that academic works were written in Latin. So, in order to understand their thoughts, you have to know a little bit about ancient philosophy. Enjoy the timeline below:

Storytime!

There is one ancient school of philosophy that I'd like to introduce at this point. I'm housing this section within a Storytime! because very little is known about the founder of this movement. For all I know, none of what I've written in the next paragraph is true. Here we go!

Pyrrho (born circa 360 BCE) is credited as the first Greek skeptic philosopher. It is reputed that he travelled with Alexander (so-called "the Great") on his campaigns to the East. It is there that he came to know of Eastern mysticism and mindfulness. And so he came back a changed man. He had control over his emotions and had an imperturbable tranquility about him.

Here's what we do know. He was a great influence on Arcesilaus (ca. 316-241 BCE) who eventually became a teacher in Plato's school, the Academy. Arcesilaus' teachings were informed by the thinking of Pyrrho, and this initiated the movement called Academic Skepticism, the second Hellenistic school of skeptical philosophy. This line of thinking continued at least into the third century of the common era.

Skepticism is a view about knowledge, namely that we cannot really know anything. The branch of philosophy that focus on matters regarding knowledge is epistemology. You'll learn more about that below in Decoding Epistemology.

Decoding Epistemology

The Regress Argument

Although Pyrrhonism is interesting in its own right, we won't be able to go over its finer details here. In fact, we will only concern ourselves with one argument from this tradition. In effect, the last piece of the puzzle in our quest for context will be the regress argument, a skeptical argument whose conclusion states that knowledge is impossible. The regress argument, by the way, is also known as Agrippa’s Trilemma, named after Agrippa the Skeptic (a Pyrrhonian philosopher who lived from the late 1st century to the 2nd century CE).

To modern ears, the regress argument seems like a toy argument. It seems so far removed from our intellectual framework that it is easy to dismiss. But, again, this is easy for you to say. You are, after all, reading this on a computer. You are assured that the state of knowledge of the world is safe. You didn't live through the Peloponnesian War, or the fall of the Roman Empire, or the Thirty Year's War. You are comfortable that science will progress, perhaps indefinitely. In other words, you don't really think that collapse is possible for your civilization. But thinkers of the past didn't have this luxury. They were concerned with basic distinctions like, for example, the distinction between knowledge and opinion.8

As such, try to be charitable when you read this argument. Today, epistemology, the branch of philosophy concerning knowledge, is more like a game that epistemic philosophers play. But in the ancient world, when the notion of rational argumentation was still in its infancy, the possibility that perhaps we can never really know anything (i.e., skepticism) was a real threat.

The argument

- In order to be justified in believing something, you must have good reasons for believing it.

- Good reasons are themselves justified beliefs.

- So in order to justifiably believe something, you must believe it on the basis of an infinite amount of good reasons.

- No human can have an infinite amount of good reasons.

- Therefore, it is humanly impossible to have justified beliefs.

- But knowledge just is justified, true belief (the JTB theory of knowledge).

- Therefore, knowledge is impossible.

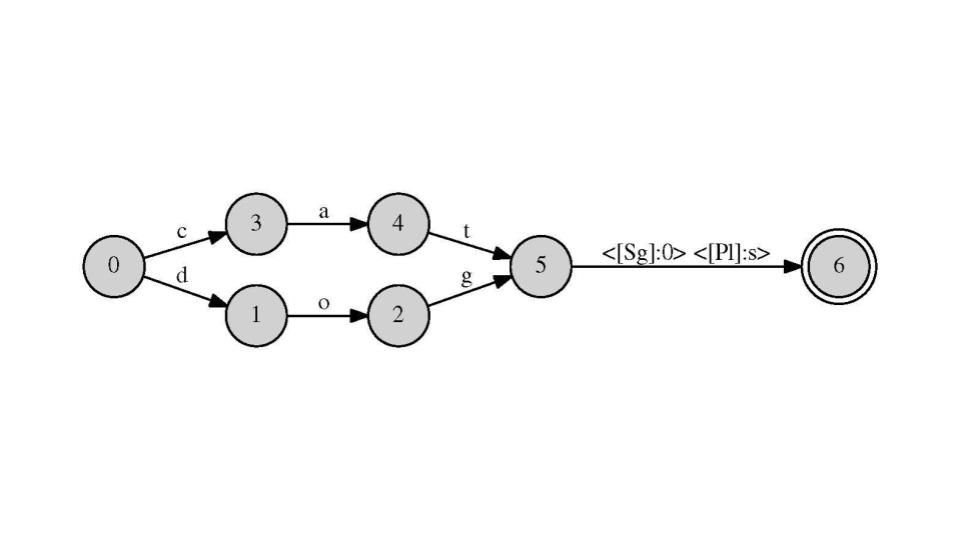

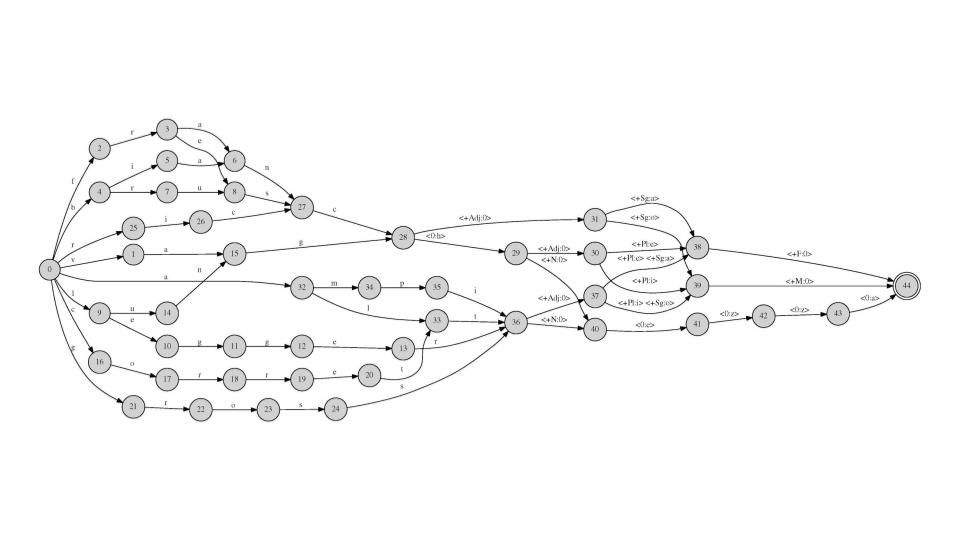

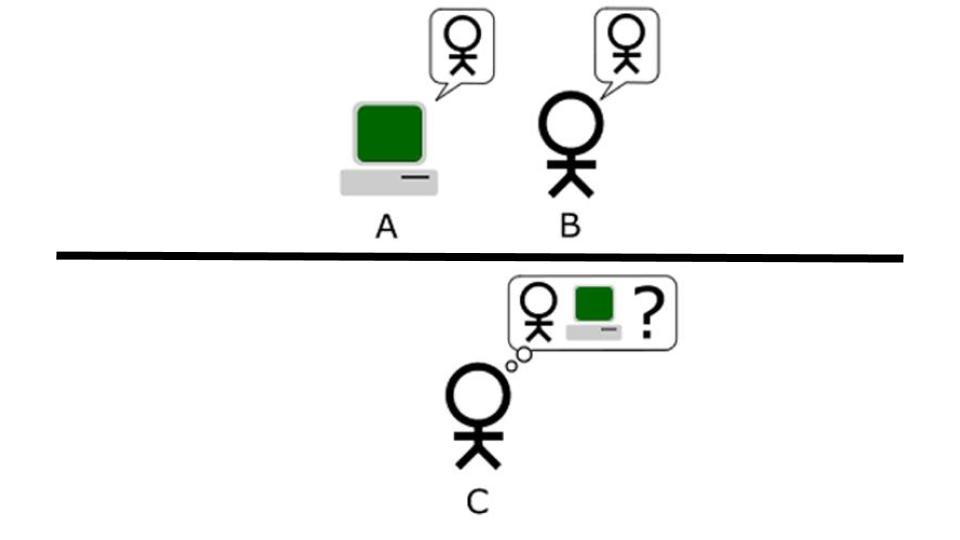

The general idea is quite simple. Consider a belief, say, "My dog is currently at home". How do you know that belief is true? You might say, "Well, she was home when I left the house, and, in the past, she's been home when I get back to the house." A skeptic would probe further. "How do you know that today won't be the exception?" the skeptic might ask. "Perhaps today's the day she ran away or that someone broke in and stole her." You give further reasons for your beliefs. "Well, I live in a safe neighborhood, so it's unlikely that anyone broke in" and "She's a well-behaved dog so she wouldn't run away" are your next two answers. But the skeptic continues, "But even safe neighborhoods have some crime. How can you be sure that no crime has occurred?" Eventually, you'd get tired of providing support for your views. Even if you didn't, it's impossible for you to continue this process indefinitely (since you live only a finite amount of time). If knowledge really is justified, true belief, then you could never really justify your belief, because every justification needs a justification. I made a little slideshow for you of the "explosion of justifications" required, where B is the original belief and the R's are reasons (or justification) for that belief. Enjoy:

According to Agrippa, you have three ways of responding to this argument (and none of them work):

- You can start providing justifications, but you’ll never finish.

- You could claim that some things don’t need further justification, but that would be a dogma (which is also unjustified).

- You could try to assume what you are trying to prove, but that’s obviously circular.

The third possibility that Agrippa points out is definitely not going to work. In fact, that form of reasoning is considered an informal fallacy, which brings us to the...

Begging the Question

This is a fallacy that occurs when an arguer gives as a reason for his/her view the very point that is at issue.

Shenefelt and White (2013: 253) give various examples of how this fallacy appears "in the wild", but the main thread connecting this is the circular nature of the reasoning. For example, say someone believes that (A) God exists because (B) it says so in the Bible, a book which speaks only truth. They might also believe that (B) the Bible is true because (A) it comes from God (whom definitely exists). Clearly, this person is reasoning in circles.

An even more obvious example is a conversation I overheard in a coffee shop once. One person said, "God exists. I know it, man." His friend responded, "But why do you believe that? How do you know that God exists?" The first person, without skipping a beat, said, "Because God exists, bro." Classic begging the question.

Two more things...

Now that you know about the high degree of religiosity and some tidbits about ancient philosophy, the setup is complete. We can begin to move towards 1600. Let me just close with two points. First, I know I left you hanging last time. Let me correct that now. The fundamental question of the course is: What is knowledge? I know it doesn't seem like it could take the whole term to answer this question, but you'd be surprised.

Second, that execution that I mentioned... Don't worry. It's coming.

There are two important bits of context that are important to understand the history being told in this class:

- The first century of the early modern period in Europe (1500-1800 CE) was characterized by a high degree of religiosity;

- There was still an active engagement between the thinkers of this early modern period and the philosophies of ancient Greece.

The distinction between deduction (which purports to give certainty) and induction (which is probabilistic reasoning) is important to understand.

The jargon (i.e., technical language) for the assessment of arguments, namely the concepts of validity and soundness are essential to know.

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that concerns itself with questions relating to knowledge.

The ancient philosophical schools of skepticism posed challenges to the possibility of having knowledge which early modern thinkers were still thinking about and working through.

The regress argument, one argument from the skeptic camp, questions whether we can ever truly justify our beliefs, thereby undermining the possibility of having knowledge (at least per the definition of knowledge assumed in the JTB theory of knowledge).

FYI

Suggested Reading: Harald Thorsrud, Ancient Greek Skepticism, Section 3

TL;DR: Jennifer Nagel, The Problem of Skepticism

Supplementary Material—

-

Video: Steve Patterson, The Logic Behind the Infinite Regress

Related Material—

-

Video: Nerwriter1, The Death of Socrates: How To Read A Painting

Advanced Material—

-

Reading: A. J. Ayer, What is Knowledge?

Footnotes

1. To add to this, there was a major philosophical debate in the 20th century over the possibility of translation (e.g., see Quine 2013/1960). Consider how, in order to translate the modes of thought and concepts of an alien culture, you need to first interpret them. But the very process of interpretation is susceptible to a misinterpretation—distortion due to unconscious biases. Perhaps the whole process of translation itself is doomed.

2. The interested student should consult Kahneman's 2011 Thinking, fast and slow or watch this helpful video.

3. Zajonc argues that this trait, to find the familiar favorable, is evolutionarily advantageous. It makes sense, he argues, that novel stimuli should be looked upon with suspicion, while familiar stimuli (which didn’t kill you in the past) can be looked on favorably (Zajonc 2001).

4. Emperor Nero took advantage of the Great Fire of 64 CE to build a great estate. Facing accusations that he deliberately caused the fire, he heaped the blame on the Christians, and a short campaign of persecution began. However, the Christians appeared to revel in the persecution. Martyrdom allowed many who were otherwise of lowly status or from a disenfranchised group (like women or slaves) to become instant celebrities and be guaranteed, they believed, a place in heaven. Martyrdom literature proliferated, and Christians actively sought out the most painful punishments (see chapter 4 of Catherine Nixey's The Darkening Age).

5. By the way, I'm not alone in using this distinction. One of the main books I'm using in building this course is Herrick (2013) who shares my view on this distinction.

6. Another common mistake that students make is that they think arguments can only have two premises. That's usually just a simplification that we perform in introductory courses. Arguments can have as many premises as the arguer needs.

7. This argument is valid but not sound, since there are some lawyers who are non-liars—although not many.

8. Interestingly, in an era of disinformation where there is non-ironic talk of "alternative facts" and "post-truth", the distinction between knowledge and opinion is once again an important philosophical distinction to make.

The Advancement of Learning

No fact is safe from the next generation of scientists with the next generation of tools.

~Stuart Firestein

Worldviews

The year 1600 marks a turning point, according to historian and philosopher of science Richard DeWitt. It was in this year that a worldview, and its set of accompanying beliefs and ideas, died. The Aristotelian worldview, which had dominated Western Thought starting at about 300BCE, finally imploded. In its wake, a deterministic and mechanical worldview came to permeate in the minds of intellectuals, scientists, and philosophers.

Now, of course, the death of abstractions is always hard to pin down. The year 1600, more than anything, is perhaps best considered a convenient record of the hour of death. Even more evasive than determining the time of death of an abstraction may be coming to an agreement over its cause of death. Even though there is nothing analogous to, say, cardiac arrest for an abstraction, there is what we might call a natural death: some ideas simply run their course and are abandoned. This, we can say with considerable certainty, was not what happened to the Aristotelian worldview. Speaking crudely, this worldview lived past its prime and its usefulness, and so it was put down deliberately via the concerted effort of many of the most famous names in science and philosophy—Copernicus, Galileo, Descartes, Kepler, and Newton (to name a few). Its cause of death, in short, was violent.

To understand how a worldview dies, however, we should probably begin with some basics. What is a worldview, anyhow? And how do abstractions die? What was the Aristotelian worldview? What replaced it? We take these in turn.

Jigsaws

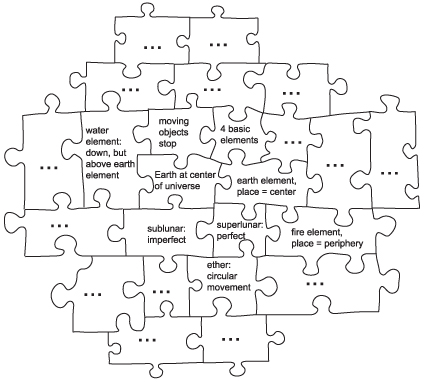

DeWitt begins his Worldviews by clarifying the notion of a worldview. He likens beliefs to a jigsaw puzzle. To have a worldview is to have a system of beliefs where the beliefs fit together in a coherent, rational way. In other words, the beliefs of our worldview should fit together like the pieces of a puzzle. We wouldn't, for example, both believe that the Earth is the center of the universe and that our solar system revolves around the center of the Milky Way galaxy. There, of course, can't be two centers. And so, at least when we are being our best rational selves, develop consistent, rational jigsaw puzzles of beliefs.

Moreover, the central pieces tend to be more important. These are what allow the rest of our beliefs to fit in or cohere with each other. Without the central pieces the outer pieces are just "floating", with no connection to the center or to each other. It may be that, as it happens to be the case with me, when you are assembling a jigsaw, sometimes you change the location of the outer pieces. You thought it went in the lower-right quadrant, but it turns out it belongs in the upper left. Analogously, less central beliefs in our worldview might be updated or even discarded, but the central beliefs are integral to the system. The central beliefs give the system meaning and form.

The Aristotelian Worldview

The Aristotelian Jigsaw

(borrowed from

DeWitt 2018: 10).

Before proceeding, it should be said that what is called the Aristotelian worldview is not exactly what Aristotle believed. Rather, it takes as a starting point several beliefs held and defended by Aristotle and grows from there. Having said that, let's take a look at some of these beliefs:

- The Earth is located at the center of the universe.

- The Earth is stationary.

- The moon, the planets, and the sun revolve around the Earth in roughly 24hr cycles.

- The region below the moon, the sublunar region, contains the four basic elements: earth, water, air, fire.

- The region above the moon, the superlunar region, contains the fifth element: ether.

- Each of the elements has an essential nature which explains their behavior.

- The essential nature of the elements is reflected in the way the elements move.

- The element earth has a tendency to move towards the center of the universe. (This explains why rocks fall down, since the Earth is the center of the universe.)

- The element of water also has a tendency to move toward the center of the universe, but this tendency is not as strong as that of earth. (This is why when you mix dirt and water, the dirt eventually sinks.)

- The element air naturally moves away from the center of the universe. (That’s why when you blow air into water, the air bubbles up.)

- Fire also tends to naturally move away from the center of the universe. (That is why fire rises.)

- Ether tends to move in circles. (This is why the planets, which are composed of ether, tend to move in circular motions around the Earth.)

Slow down there, Turbo...

I've sometimes encountered people, including people who should know better, who naively believe that people who held the Aristotelian worldview were "simple-minded" or even "stupid". I assure you, they had the same (roughly speaking) mental machinery that you and I have. In the case of Aristotle, Ptolemy, and others, I'm actually willing to wager that they were much smarter than even the average college professor. Moreover, they had what were—at the time—very good rational and empirical arguments for their beliefs. I'm sure that if you were around in those days, you would've bought into these.

DeWitt (ibid., 81-91) summarizes some arguments for the Aristotelian viewpoint from Ptolemy’s Almagest (published ca. 150 CE). For example, it was known that the Earth was spherical since objective events, like eclipses, were recorded at different times in different places, and the difference in time was proportional to the distances between locations. By studying the regularity of the sun rising in the East prior to more westerly locations, the ancients reasoned that the curvature of the Earth is more or less uniform. Having established the east-west spherical nature of Earth, which is compatible with Earth being a cylinder, he then notes that some stars are only visible the further north one goes. The same goes when traveling south. This suggests that Earth is spherical in the north-south direction too, thereby establishing that Earth is spherical.

Even though you agree (I hope) that the Earth is spherical, could you have come up with those arguments? It's important to remember that our ancestors were not naive.

It's instructive also, I think, to look at beliefs you likely don't agree with. Ptolemy gives some common-sense arguments for geocentrism: the belief that the Earth is the center of the solar system and/or the universe. Here's one such argument. The ancients knew that the Earth’s circumference was about 25,000 miles. Assuming that the Earth rotates on an axis would lead to the conclusion that a full rotation takes 24 hours. This would mean that, if we are standing at the equator, we would be spinning at over 1,000 miles per hours (since 25,000 miles / 24 hours = 1,041.7 mph). This speed would obviously be compounded by an Earth that is also orbiting around a sun. But obviously, it doesn’t even feel like we are moving at 1,000 mph, so considering greater distances is unnecessary. Heliocentrism simply doesn’t match with our everyday experience, since it doesn't at all feel like we are on a sphere travelling at well over a thousand miles per hour.

Here's another argument. Objects don’t typically move without some external force acting on them. Try it if you want to convince yourself. Earth, moreover, is a very large object. It stands to reason that only if a very massive force was moving it would Earth move. But no massive force is immediately evident. So it is reasonable to infer that Earth is stationary.

The aforementioned arguments could perhaps be dubbed "common-sense" arguments. Ptolemy also gave more empirical arguments about the nature of falling objects and stellar parallax, but these are a little more technical than what is needed to prove the basic point I want to make: the ancients were not dumb. In fact, in section 7 of the preface to Almagest, Ptolemy even briefly considers the mechanics heliocentrism(!). Also, it is noteworthy that it took the combined efforts of some of the biggest names in science, as we've already mentioned, to dethrone geocentrism. Relatedly, Ptolemy's model of the solar system was unrivaled in predictive power for 1400 years. Lastly, most educated people beginning around 400 BCE correctly believed that the Earth was spherical, as we do. In sum, the ancients were no slouches.

How do worldviews die?

Recall the analogy between worldviews and jigsaw puzzles. It is the central pieces that hold most of the import. These central pieces connect what would otherwise be disunited and seemingly unrelated components. The center is, in short, the beating heart of the worldview. Worldviews die when its central tenets are no longer believed.1

The magicians

We find ourselves in London in the year 1600. We are in the tail end of the Tudor Period (1485-1603), which is generally considered to be a "golden age" in English history. Queen Elizabeth I is on the throne as she has been since 1558, and what a reign it's been. Advancements in cartography and the study of magnetism have led to an increase in maritime trade. The British navy itself was doing very well. In the summer months of 1588, the English defeat the Spanish Armada, which had previously been thought to be invincible. There were no major famines or droughts, and there was an increase in literacy rates. It's even the case that, towards the end of Elizabeth's reign, in the early 1590's, Shakespeare's plays were beginning to hit the stage.

It was during this time period that some pivotal steps towards modern science were taken. It was a few decades earlier, in the middle of the 1500s, that there were remarkable innovations in the making and use of tools of observation, as well as ways of conceptualizing and categorizing one’s findings. Tools of observation and systematizing our beliefs (an inheritance from Aristotle), of course, are essential to science. But by 1600, one idea more than any of the others was catching in certain intellectual circles: the idea of the controlled experiment.

Prior to this time period, when one experimented, what one really meant by that was merely to say that they tried something. In fact, in some Spanish-speaking countries, the Spanish word for experiment (experimentar) is still used to mean something like, "to see what something feels like." But the word experiment was shifting in meaning. It was, in some specialized circles, starting to mean an artificial manipulation of nature; a careful controlled examination of nature. This would eventually lead to a complete paradigm shift. Lorraine Daston writes:

“Most important of these [innovations] was ‘experiment,’ whose meaning shifted from the broad and heterogeneous sense of experimentum as recipe, trial, or just common experience to a concertedly artificial manipulation, often using special instruments and designed to probe hidden causes” (Daston 2011: 82).

Who were these early experimentalists? Like all great movements, the experimentalist movement went through three stages: ridicule, discussion, adoption. Although this may pain those of us who are science enthusiasts, the early experimentalists were looked upon as... well... weird. They typically spent most of their free time engaging in experiments and would let other social and professional responsibilities lapse. They would spend an inordinate amount of their money on their examination of nature, and they would mostly socialize only with other experimentalists. Daston again:

“[O]bservation remained a way of life, not just a technique. Indeed, so demanding did this way of life become that it threatened to disrupt the observer’s other commitments to family, profession, or religion and to substitute epistolary contacts with other observers for local sociability with relatives and peers... French naturalist Louis Duhamel du Monceau depleted not only his own fortune but that of his nephews on scientific investigations. By the late seventeenth century, the dedicated scientific observer who lavished time and money on eccentric pursuits was a sufficiently distinctive persona in sophisticated cultural capitals like London or Paris to be ridiculed by satirists and lambasted by moralists” (Daston 2011: 82-3).

Stage 2: Discussion

Enter Francis Bacon (1561-1626). By 1600, Bacon had already served as a member of Parliament and had been elected a Reader, a lecturer on legal topics. But the aspect of Bacon's work that was truly novel was his approach to natural science. Bacon struggled against the traditional Aristotelian worldview as well as the mixture of natural science and the supernatural. He re-discovered the pre-Socratics and was fond of Democritus and his atomism: the view that the world is composed of indivisible fundamental components. He also had a clear preference for induction, contrary to many of his contemporaries.

In 1605, Bacon publishes The Advancement of Learning in which he rejects many Aristotelian ideas. In book II of Advancement, he argues that we must cleanse ourselves of our “idols” to engage in empirical inquiries well. These idols include intuitions rooted in our human nature (idols of the tribe), overly cherished beliefs of which we can’t be critical (idols of the cave), things we hear from others but never verify (idols of the market place), and the ideological inheritance of accepted philosophical systems (idols of the theater).

Instead, Bacon argues that the only way to know something is to be able to make it, to control it. In other words, making is knowing and knowing is making. The way this idea is most often encapsulated is in the following phrase: Knowledge is power. As it turns out, this controlling of nature overawed early experimentalists. Bacon even referred to this applied science as "magic".

Regress? What regress?

In the last lesson, we were introduced to an argument from the skeptic camp, an argument that concluded that knowledge, as conceived of by Plato, is impossible. I joked that this is more like a game to contemporary epistemic philosophers, but I wasn't completely kidding. At least some epistemic philosophers do see it that way (e.g., Williams 2004). If it is a game, then, we should be able to solve it. Bacon provides us with one possible approach: change the definition of knowledge.

Take a look once more at the regress argument:

- In order to be justified in believing something, you must have good reasons for believing it.

- Good reasons are themselves justified beliefs.

- So in order to justifiably believe something, you must believe it on the basis of an infinite amount of good reasons.

- No human can have an infinite amount of good reasons.

- Therefore, it is humanly impossible to have justified beliefs.

- But knowledge just is justified, true belief (the JTB theory of knowledge).

- Therefore, knowledge is impossible.

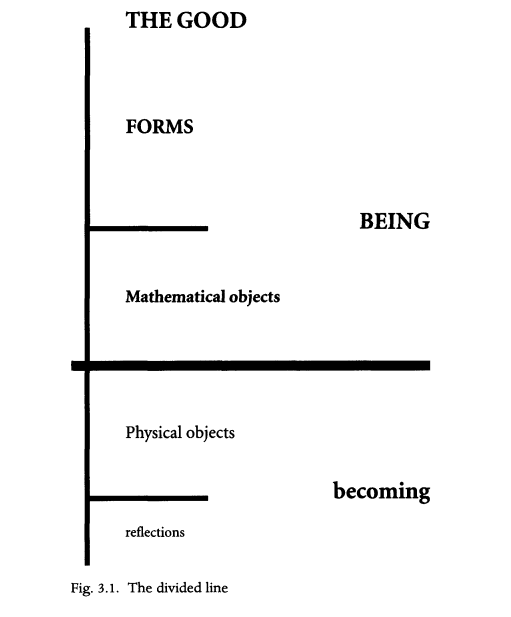

Notice that the word "justification" is featured prominently throughout the argument. This is important because this argument, then, is assuming Plato's JTB theory: knowledge is justified, true belief. As such, one way to diffuse this argument is to not assume Plato's JTB theory. This is precisely what Bacon is doing, and this is no accident.

Bacon rejects the Aristotelian tradition of what he calls the "anticipation of nature" (anticipatio naturae), and argues that we should instead interpret nature through the rigorous collection of facts derived from experimentation. Knowledge isn't "justified, true belief." Bacon couldn't care less whether or not his knowledge claims were justified in the eyes of Platonists. The only question for Bacon is, "Can you control nature?" If you can, that's enough to say that you know how nature works. This should be the true goal of science: to interrogate and ultimately control our natural environments and actively work towards bringing about a utopian transformation of society. Mathematicians and historian of mathematics Morris Kline puts it this way:

“Bacon criticizes the Greeks. He says that the interrogation of nature should be pursued not to delight scholars but to serve man. It is to relieve suffering, to better the mode of life, and to increase happiness. Let us put nature to use... ‘The true and lawful goal of science is to endow human life with new powers and inventions’ ” (Kline 1967: 280).

Many students find Bacon's views intuitively appealing, and they very well may be. We will put off critiquing them until the next section. For now, let me stress how this relates to our overall project.

Dilemma #1: How do we solve the regress?

So far, we've been introduced to the branch of philosophy known as epistemology, which concerns itself with questions relating to knowledge. We've seen one possible definition of knowledge (the JTB theory) and one objection to that theory (given via the regress argument) from one camp of thinkers who believe that knowledge is impossible (the skeptics). Let's flag this spot in the conversation and call it Dilemma #1. This dilemma is, in a nutshell, this: how do we stop the skeptic's regress argument?

Bacon provides us with one solution: change the definition of knowledge. In the next section, we will introduce some problems with this solution. In the lessons to come, we will look at alternate solutions coming from different theorists. Only then will we be able to judge which is the best solution.

I might add that this will be the general trajectory of the course. There will be 10 dilemmas in all, and each will be associated with a number of different solutions. These dilemmas are all interrelated, as you'll see. They are also connected to fundamental ideas in Western thought. Fun times ahead.

Bacon's legacy

Bacon's public career ended in disgrace. Although it was an accepted practice at the time, Bacon received gifts from his litigants and his political rivals used this to charge him with corruption. He was removed from public office, and he devoted the rest of his days to study and writing. He died in 1626.

His legacy lives on, however. Per Daston, “Baconians [those who subscribed to Bacon's ideas] played a key role in the rise of the terminology of observation and experiment in mid-seventeenth-century scientific circles” (Daston 2011: 83; interpolation is mine). Moreover, since the practice of science doesn’t come to fruition just from a common methodology, Bacon also suggested a way for establishing joint ground and sharing insights. In New Atlantis (published posthumously in 1626), an incomplete utopian novel, Bacon discussed the House of Salomon, a concept that influenced the formation of scientific societies, societies which still live on today. Daston again: “[T]he scientific societies of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries shifted the emphasis from observation as individual self-improvement, a prominent theme in earlier humanist travel guides, to observation as a collective, coordinated effort in the service of public utility” (Daston 2011: 90).

Decoding Pragmatism

Some comments

At this point we've introduced a second contender into the fray: pragmatism. We've also complicated our epistemic picture a little bit, so I'd like to make sure everyone's on board with this:

We have two different definitions of what knowledge is: Plato's JTB theory and pragmatism.

We have two different theories for justifying knowledge claims: the correspondence theory of truth and the coherence theory of truth.

We have two different conceptions of the aims of science: realism and instrumentalism.

Lastly, these different views tend to cluster together: JTB fits in nicely with the correspondence theory of truth and realism, while pragmatism tends to fit in nicely with coherentism and instrumentalism.

Putting on our historical lenses

It may be the case that you've already picked which view you agree with. That's fine. But now I want you to think about what view would've seemed more sensible at the turn of the 17th century. If you were there at Bacon's funeral, would you have bet on his ideas catching and taking off? Would you have wanted them to?

It's hard for us to put ourselves in the right frame of mind to understand and to feel what someone from the 1600's might've thought and felt. We are, in a very real way, jaded. But we have to realize this: the great success of the natural sciences that we enjoy the fruits of today was not yet empirically validated in the 17th century. In other words, if you were there, and you were looking at these "experimentalists" and "magicians", you could reasonably argue that society should not to take the plunge. You found yourself at the crossroad. Would you choose the worldview that had dominated Western thought for over a thousand years (i.e., the devil you know) or would you take a chance with this new natural science stuff? I'm sure that we'd like to think that we would've been early adopters of the latest ideas, but consider for a moment how uncertain this new worldview must've seemed.

All in pieces...

To be honest, to only focus on the nascent scientific method is to grossly underestimate the feeling of inconstancy that was gripping society in the 1600s. It was a time of intellectual and social upheaval, sometimes violent; and it had been for a few centuries.

My guess is that most of us would have felt the same feeling of precariousness. It all felt on the verge of collapse. I close with Morris Kline's words:

“It was to be expected that the insular world of medieval Europe accustomed for centuries to one rigid, dogmatic system of thought would be shocked and aroused by the series of events we have just described. The European world was in revolt. As John Donne put it, ‘All in pieces. All coherence gone” (Kline 1967: 202).

Around the year 1600, the Aristotelian worldview, which had dominated Western Thought since roughly 300BCE, finally gave way to a new more mechanistic worldview.

During this time period, the concept of an experiment began to be developed, and experimentalists enthusiastically took to the analysis of nature.

The ideas of Francis Bacon were instrumental in standardizing and codifying the concepts of experiment, scientific societies, and eventually the scientific method itself.

Pragmatism is a competing conception of knowledge.

There are two constellations of views that fit well together:

- JTB theory + the correspondence theory of truth + realism about science

- pragmatism + coherence theory of truth + instrumentalism about science

FYI

Suggested Reading: Lorraine Daston, The Empire of Observation, 1600-1800

-

Note: The suggested reading is only the first 11 pages of the document. Here is a redacted copy of the reading.

TL;DR: 60Second Philosophy, Who is Francis Bacon?

Supplementary Material—

-

Reading: David Simpson, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Entry on Francis Bacon

Related Material—

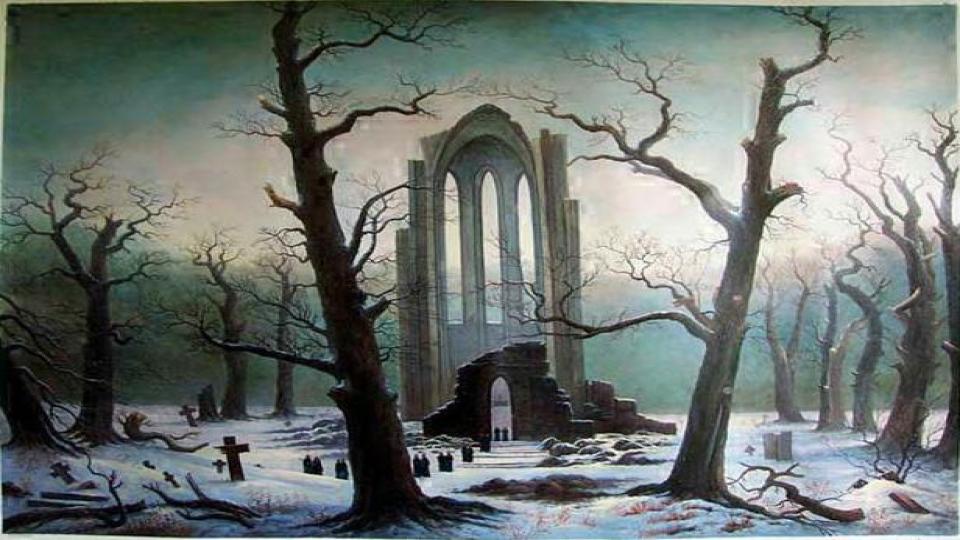

- Video: Smarthistory, Friedrich, Abbey among Oak Trees

- Note: This is an analysis of the work of Caspar David Friedrich, one of my favorite artists. I use his paintings throughout this course. One painting in particular, his Monastery Ruins in the Snow, is the image I use to represent the feeling of being trapped in the pit of skepticism.

Advanced Material—

-

Reading: Francis Bacon, Novum Organum

-

See in particular Book II.

-

-

Reading: Jürgen Klein, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Entry on Francis Bacon

Footnotes

1. DeWitt and I are both heavily influenced by the work of physicist/philosopher Thomas Kuhn (2012), as are many. This is not to say that DeWitt (or I) agree completely with Kuhn, though. Nonetheless, this whole way of speaking is reminiscent of Kuhn's The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, originally published in 1962. The interested student can find a copy of this work or watch this helpful video.

Cogito

If you would be a real seeker after truth, it is necessary that at least once in your life you doubt, as far as possible, all things.

~René Descartes

Aristotle's dictum

Up to this point, we've been using the analogy between worldviews and jigsaws or between worldviews and webs of beliefs (which was philosopher W.V.O. Quine's preferred metaphor). Analogies, unfortunately, have their limitations. As it turns out, there are aspects of the downfall of worldviews that are decidedly not like a jigsaw puzzle (or a spider's web, for that matter). For example, once a worldview is torn apart, it is not uncommon for thinkers to parse through the detritus, find a pearl, and incorporate it into their new worldview. This would be as if someone, after breaking apart the completed jigsaw puzzle that decorated their living room coffee table, were to then take a prized puzzle piece from that set and use it in a different jigsaw. Surely that doesn't make much sense. Nonetheless, this is how the partitioning of worldviews goes: not all beliefs are tossed. There are always some pearls of wisdom that can be updated, or otherwise adapted to the new normal.

First, some context. If I painted too rosy a picture of the end of the Tudor period in the last lesson, you will forgive me—I hope. My perception might have been altered by my knowledge of what happened next. As if we needed a reminder that, in the past, societal advancements were often accompanied by backtracking, both nature and established institutions pushed back against intellectual progress and stability—with a vengeance. In 1600, for example, philosopher and (ex-)Catholic priest Giordano Bruno was burned at the stake for his heretical beliefs in an infinite universe and the existence of other solar systems. Even more tragic, if only because of the sheer magnitude of the numbers involved, was the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648), which claimed the lives of 1 out of 5 members of the German population. This began as a war between Protestant and Catholic states. However, fueled by the entry of the great powers, the conflict wrought devastation to huge swathes of territory, caused the death of about 8 million people, and basically bankrupted most of the belligerent powers.

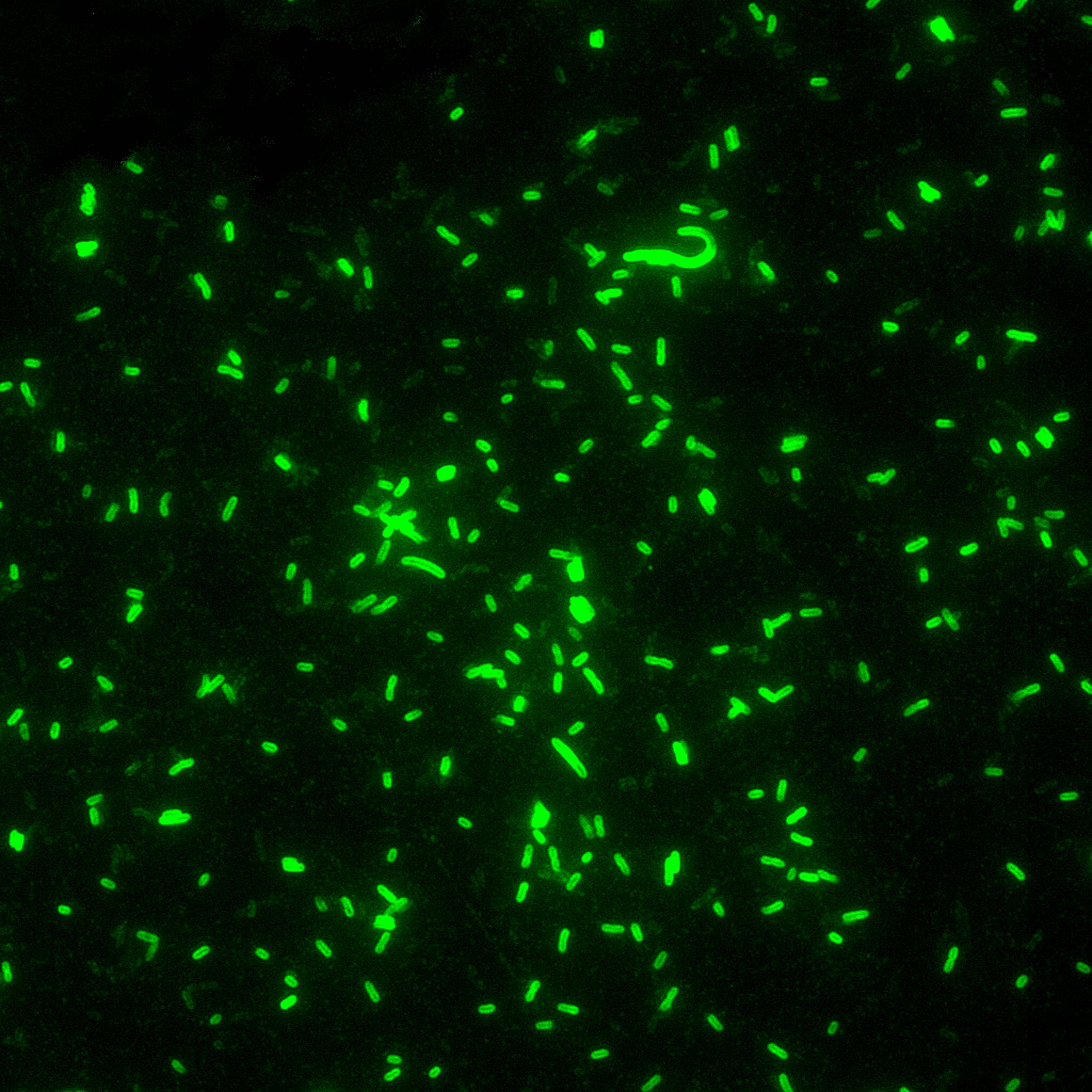

Yersinia pestis, the bacteria

which causes plague.

As if human-made suffering isn't unhappy enough, Mother Nature often only compounds the agony. In 1601, due to a volcanic winter caused by an eruption in Peru, Russia went through a famine that lasted two years and killed about one third of the population. There were also intermittent resurgences of bubonic plague in Europe, northern Africa, and Asia throughout the 17th century. I, of course, don't have to tell you that a tiny virus 125 nanometers in size can cause major cultural, political, and economic disruptions.

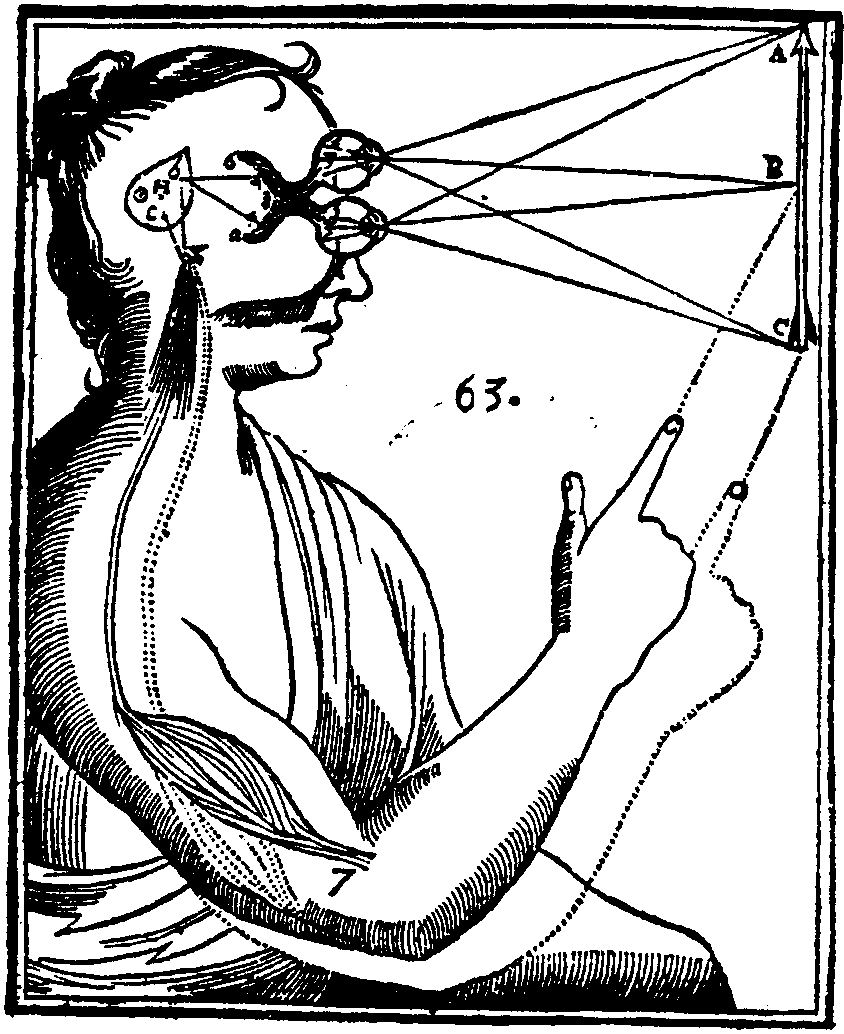

But thinkers of the time did not know yet about germ theory, let alone climate science. The former would have to wait until the work of Louis Pasteur in the 1860s. Intellectuals instead focused on a domain that they felt they might be able to affect: our religious convictions. Thinkers like René Descartes (the subject of this lesson whose name is pronounced "day-cart") and John Locke (the subject of the next lesson) noticed that religious fanatics could reason just as well as logicians. The problem, they thought, was that they began with religious assumptions that they took to be universal truth. From these dubious starting points these fanatics were able to justify the killing of heretics, the torture of witches, and their religious wars. In other words, these thinkers, like many others of their age, wanted to ensure that people reasoned well, that people would filter their beliefs and discard those that didn't stand up to scrutiny. A worthy goal, indeed.

How should we reason? Descartes believed that our premises must be more certain than our conclusions. In other words, we must move from propositions that we have more confidence in to those that we have less confidence in (at least initially, before argumentation). In fact, however, Aristotle had made this point in his Posterior Analytics almost two thousand years before (I.2.72.a30-34). As such, we will call this principle, that we should move from propositions that we have more confidence in to those that we have less confidence in, Aristotle's dictum. Remember: never throw out the baby with the bathwater.

Reasoning Cartesian style

Descartes gives the metaphor of a house. We must build the house on a strong foundation, otherwise it collapses. Similarly, we must move from certain (or near certain) premises on towards our conclusion. Aristotle, by the way, speaks in a similar language. Aristotle talks about how our premises are the “causes” of our conclusions, but he’s talking about sustaining causes, the supports that keep our conclusions from crashing down.

Cartesian coordinates.