Rationalism v. Empiricism

El original es infiel a la traducción.

(The original is unfaithful to the translation.)

~Jorge Luis Borges

Jigsaws, revisited

What do you think about when you hear that some physicists now believe that it's not only our universe that exists, but that there are innumerable—maybe infinite—universes in existence? It certainly is a strange idea, and I can imagine a variety of different responses. Some might be in awe. Others might be in disbelief. Some might think it is completely irrelevant to their life, especially if you are a member of a historically/currently disenfranchised group. I'm reminded of the Russian communist Vladimir Lenin's response to the possibility that there is a 4th dimension of space. Apparently Lenin shot back that the Tsar can only be overthrown in three-dimensions, so the fourth doesn't matter.

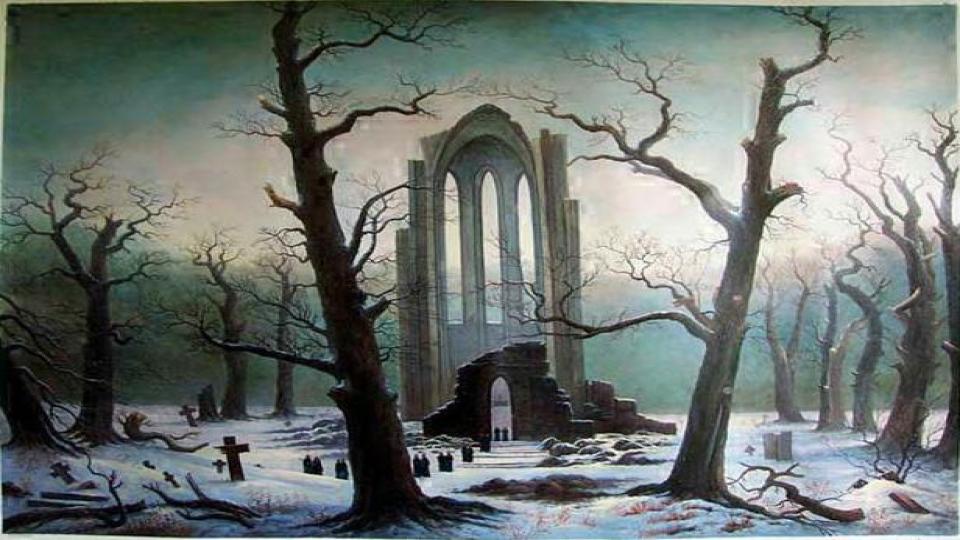

My guess, however, is that these possibilities were not open to people of the 17th century. The Aristotelian worldview that had just been dethroned was a worldview that had purpose built into it. Let me explain. Recall that in the Aristotelian worldview, each element had an essential nature. Moreover, each element's behavior was tied to this essential nature. This is called teleology, the explanation of phenomena in terms of the purpose they serve. These explanations are, if you were to truly believe them, extremely satisfactory. And so, there is something psychologically alluring about Aristotle's teleological science. Losing this purpose-oriented explanation must've been accompanied with substantial distress, intellectual and otherwise.

The distress of uncertainty lasted almost a century. Thinkers were arguing about what would replace the Aristotelian vision. And then, in 1687, Isaac Newton publishes his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, and a new worldview was established. Natural philosophy (i.e., what would eventually be called "science") went from teleological (goal-oriented or function-oriented) explanations to mechanistic explanations, which are goal-less, function-less, and purpose-less. This was, psychologically, probably worse for the people of the time. Not only did humans realize they are not living in the center of the universe, the function-oriented type of thinking they had been using for a thousand years had to be supplanted by cold, lifeless numbers.

And yet, as the saying goes, if you want to make an omelette, you gotta break some eggs. There were some unexpected benefits to the downfall of the Aristotelian worldview outside of the realm of science, philosophy, and mathematics. There were important social revolutions during this time period, and some thinkers link them to the end of teleological views:

“Likewise, the general conception of an individual’s role in society changed. The Aristotelian worldview included what might be considered a hierarchical outlook. That is, much as objects had natural places in the universe, so likewise people had natural places in the overall order of things. As an example, consider the divine right of kings. The idea was that the individual who was king was destined for this position—that was his proper place in the overall order of things. It is interesting to note that one of the last monarchs to maintain the doctrine of the divine right of kings was the English monarch Charles I. He argued for this doctrine—unconvincingly, it might be noted—right up to his overthrow, trial, and execution in the 1640’s. It is probably not a coincidence that the major recent political revolutions in the western world—the English revolution in the 1640’s, followed by the American and French revolutions—with their emphasis on individual rights, came only after the rejection of the Aristotelian worldview” (DeWitt 2018: 168).

Problems with Descartes' view

Let's return now to our story. Recall that Descartes' grand scheme was to discover foundational truths and build the rest of his belief structure upon them. However, one might lose confidence in the enterprise when one views, with justifiable dismay, the unimpressive nature of the foundational truths. Here they are reproduced:

- He, at the moment he is thinking, must exist.

- Each phenomenon must have a cause.

- An effect cannot be greater than the cause.

- The mind has within it the ideas of perfection, space, time, and motion.

These are the supposedly foundational beliefs. However, we can, it seems, question most if not all of these. Take, for example, the notion that an effect cannot be greater than its cause. Accepting that there is a wide range of ways in which we can define effect and cause, we can think of many "phenomena" that are decidedly larger than their "cause". Things that readily come to mind are:

- the splitting of an atomic nuclei and the resulting chain reaction that takes place at the detonation of an atom bomb,

- the viruses, which are measured in nanometers, and the pandemics that they cause both in antiquity as well as in the modern age, and

- the potential of lone gunman (Lee Harvey Oswald), who would otherwise be historically inconsequential, bringing about the assassination of a very historically important world leader (John F. Kennedy) and the ensuing political chaos and national mourning.

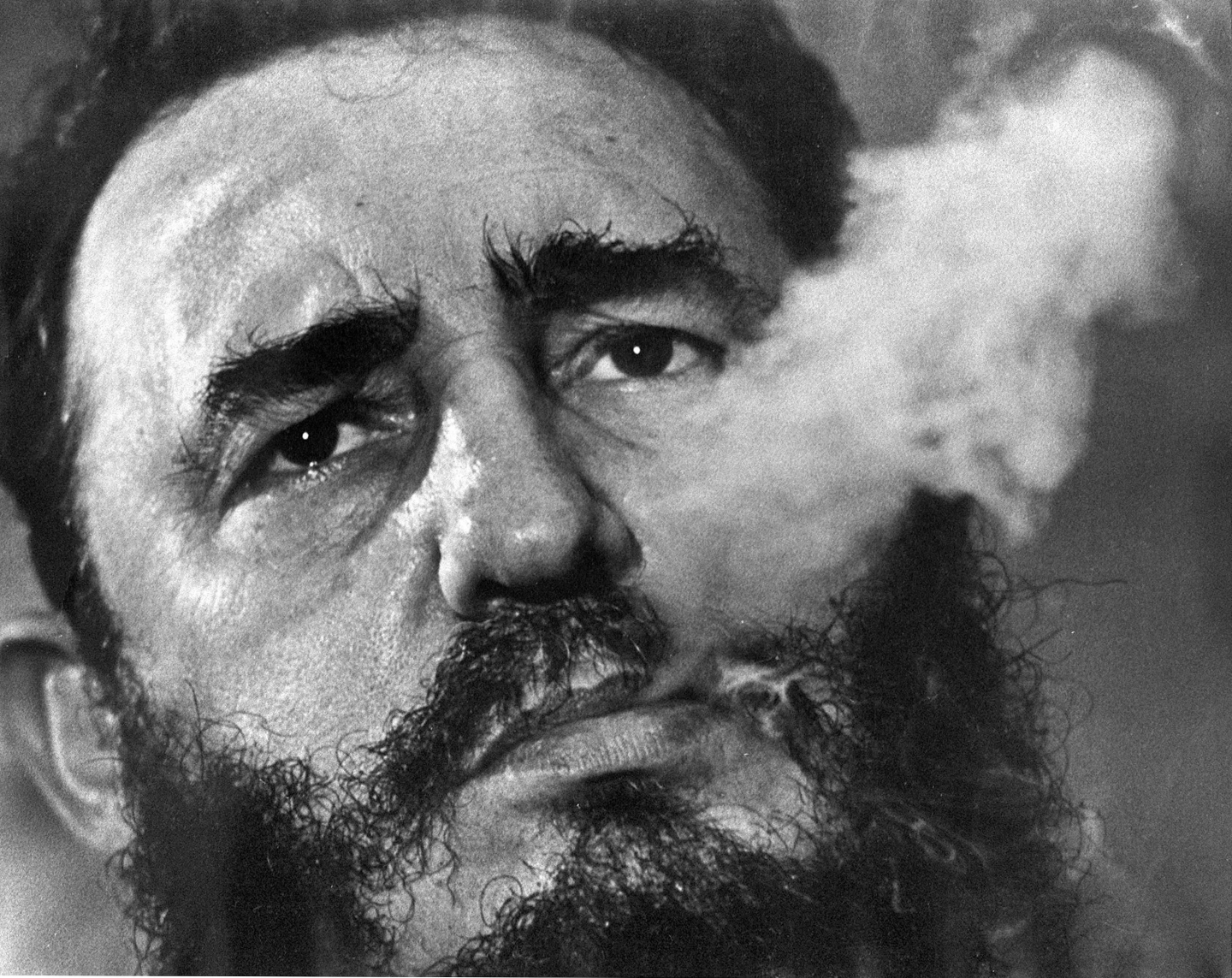

Reflecting on this last point, if this is a credible instance of an effect being smaller than the cause, it almost seems as if Descartes was vulnerable to one of the cognitive biases that many conspiracy theorists prove themselves susceptible to: the representativeness heuristic. The representativeness heuristic is the tendency to judge the probability that an object or event A belongs to a class B by looking at the degree to which A resembles B. People find it improbable that (A) a person that they would've otherwise never heard about (Oswald) was able to assassinate (B) one of the most powerful people on the planet (JFK) precisely because Oswald and JFK are so dissimilar. Oswald is a historical nobody; JFK is a massive historical actor. And it is precisely this massive dissimilarity between Oswald and Kennedy that makes it so difficult for our mind to imagine their life trajectories ever crossing. And so one might judge the event to be improbable and, if you're prone to conspiratorial thinking, you'll begin searching for alternative theories involving organized crime, the Russians, Fidel Castro, etc.1

If it walks like a duck...

One very good criticism that one can make about Descartes' foundationalist project is that, if this is supposed to be an attempt to escape skepticism, then hasn't gotten us very far. If one considers just the four foundational beliefs, it seems every bit as bad as not knowing anything at all. It might even be worse, since it gives rise to fears hitherto unconsidered. How do we know, for example, that other people have minds? How do we know we're not the only person in existence? Could it be that everyone else is a figment of our imagination or mindless robots pretending to be human? Perhaps most deviant of all is the possibility that you are in an ancestor simulation where you are the only being that has been awarded consciousness; everyone else is a specter.2

It is precisely on this point, however, that Descartes picks up his project. As it turns out, Descartes argued that he could get out of skepticism, both of the pyrrhonian variety as well as his self-imposed skepticism (also called methodological skepticism). In a nutshell, he argued that he could prove God exists and that such a perfect being wouldn’t let him be deceived about those things of which he had a “clear and distinct perception” (see Descartes' third meditation). His argument for God's existence, in an unacceptably small nutshell, was that he has an innate idea of a perfect God. An innate idea, by the way, is an idea that you are born with. Descartes, if you recall, identifies having the ideas of perfection, space, time, and motion as a foundational belief. He felt that he knew these with certainty, and that these were featured in the mind since birth. Continuing with his argument, the idea of perfection, reasons Descartes, could have only been provided (or implanted?) by a perfect being, which is God. So, God exists!

There are two things that I should say here. First, I am temporarily holding off on a substantive analysis of arguments for and against God's existence; these will occur in the next portion of the course. Stay tuned.3

Second, Descartes is essentially claiming that God rescues him (and the rest of us) from skepticism. God wouldn't allow an evil demon to deceive us. God wouldn't allow you to think your perceptions of reality are hopelessly false. Think about this for a second. Descartes was able to link evil demons with skepticism and God with knowledge. This, then, accomplishes one of Descartes' goals: to reconcile science and faith.

Having said that, Descartes' argument for God's existence has been criticized since the early modern period. One interesting exchange on this topic occurred between Descartes and Elisabeth, princess of Bohemia. The two exchanged letters for years, and on numerous instances Elisabeth questioned whether we really knew whether God is doing all the things Descartes said God was doing, such as helping us to establish unshakeable knowledge of the world. Although I've not read all the letters, it is my understanding that Descartes never argued for his claims to Princess Elisabeth's satisfaction.

Princess Elisabeth is a nice respite from this otherwise male-dominated world. Nonetheless, due to the "greatest hits" nature of introductory philosophy courses, our next stop is another white male. However, he is one that you may have heard of before: John Locke. We turn to his take on knowledge next.

Two camps

The rift between Locke and Descartes is best understood in terms of a helpful if controversial division of thinkers from the early modern era into two camps: rationalism and empiricism. Rationalism is the view that all claims to knowledge ultimately rely on the exercise of reason. Rationalism, moreover, purports to give an absolute description of the world, uncontaminated by the experience of any observer; it is an attempt to give a God’s-eye view of reality. In short, it is the attempt to reach deductive certainty with regards to our knowledge of the world.

The best analogy to understanding rationalism is through deductive certainty in geometry. In his classic mathematics text, Elements of Geometry, the Greek mathematician Euclid began with ten self-evident claims and then rigorously proved 465 theorems. These theorems, moreover, were believed to be applicable to the world itself. For example, if one is trying to divide land between three brothers, one could use some geometry to make sure that everyone gets exactly their share. This general strategy of starting with things that you are certain of and building from there should sound familiar: it is what Descartes did. If you're guessing that Descartes is a rationalist, you are correct.

“In Euclidean geometry… the Greeks showed how reasoning which is based on just ten facts, the axioms, could produce thousands of new conclusions, mostly unforeseen, and each as indubitably true of the physical world as the original axioms. New, unquestionable, thoroughly reliable, and usable knowledge was obtained, knowledge which obviated the need for experience or which could not be obtained in any other way. The Greeks, therefore, demonstrated the power of a faculty which had not been put to use in other civilizations, much as if they had suddenly shown the world the existence of a sixth sense which no one had previously recognized. Clearly, then, the way to build sound systems of thought in any field was to start with truths, apply deductive reasoning carefully and exclusively to these basic truths, and thus obtain an unquestionable body of conclusions and new knowledge” (Kline 1967: 149).

Empiricism, on the other hand, argues that knowledge comes through sensory experience alone. There is, therefore, no possibility of separating knowledge from the subjective condition of the knower. By default, empiricism is associated with induction since they reject the possibility of deductive certainty about the world. John Locke, the thinker featured in this lesson, was an empiricist.

Each of these camps embodies an approach to solving issues in epistemology during that time period, from 1600 to about 1800. However, we should add two details to give a more accurate (yet complicated) view about these opposing camps. First, these thinkers never referred to themselves as rationalists or empiricists. These are labels placed on them after the fact by another philosopher, Immanuel Kant. Moreover, these labels have a different meaning in this context. Typically, today the word rationalism is given to anyone who is committed to reason and evidence in their belief-forming practices. This is not how we are using the term in this class. Here, rationalism refers to this camp of thinkers who sought to establish deductive certainty about the world.

An excerpt of Leibniz's notebook.

Second, it might even be the case that these thinkers would be hostile to the labels we've given them. Rationalists, predictably, were committed to mathematics. Descartes, as we've discussed, is famous for some of his mathematical breakthroughs. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, another rationalist, had insights that led him to the development of differential and integral calculus independently of and concurrently with Isaac Newton. Nonetheless, any careful reader sees very different approaches between these two thinkers (Descartes and Leibniz), thinkers who are allegedly in the same camp. And while ascribing a joint methodology to the rationalists is suspect, it is even more contentious to put the “empiricists” into a single camp. This is because there are well-documented cases of “empiricists” denouncing empiricism (see in particular Lecture 2 of Van Fraassen 2008). In short, this is a useful distinction, but one should not fall into the trap of believing that the two sides are completely homogenous.

“This convenient, though contentious, division of his predecessors into rationalists and empiricists is in fact due to Kant. Believing that both philosophies were wrong in their conclusions, he attempted to give an account of philosophical method that incorporated the truths, and avoided the errors, of both” (Scruton 2001: 21; emphasis added).

The human

John Locke (1632-1704) was a physician and philosopher and is commonly referred to as the "Father of Liberalism". In 1667, Locke became the personal physician to Lord Ashley, one of the founders of the Whig movement (a political party that favored constitutional monarchy, which limits the power of the monarch through an established legal framework, over absolute monarchy). When Ashley became Lord Chancellor in 1672, Locke became involved in politics, writing his Two Treatises of Government during this time period. Two Treatises of Government is a sophisticated set of arguments against the absolute monarchism defended by Thomas Hobbes and others. In 1683, some anti-monarchists planned the assassination of the king; this is known as the Rye House Plot. The plot failed and, although there is no direct evidence that Locke was involved, he fled to Holland. There, he turned to writing once more. In 1689, he publishes his Essay Concerning Human Understanding, the main subject of this lesson.

Decoding Locke

Signpost

At this point, we have three competing ways of conceptualizing knowledge: positivism, Cartesian foundationalism, and Lockean indirect realism. It might be helpful to at this point provide images for associating each of these. Enjoy the slideshow below:

These are incompatible perspectives. Moreover, Descartes and Locke have an added layer of conflict. Descartes clearly assumes that the foundation of all knowledge is the foundational beliefs established through reason, not beliefs acquired through the senses. Locke states exactly the opposite view: the mind is empty of ideas without sensory experience. The ultimate foundation of knowledge is sensory experience. We will identify this debate about the ultimate foundation of knowledge as "Dilemma #2: Empiricism or Rationalism?".

Problems with Locke's view

Just like Descartes' view has some issues, Locke's view doesn't seem to really help us escape from skepticism either. First and foremost, Locke admits that there is no way we can ever check that our ideas of the world actually represent the world itself. We can be sure, Locke claims, that our simple ideas do represent the world, but an ardent skeptic would challenge even this. The only way you could know that your representations of the world correspond to the world is if you compare them; but this is impossible on Locke's view. This is, in fact, the argument that a fellow empiricist, George Berkeley, levied against Locke.

Speaking of empiricism, here's another challenge to Locke. The empiricist camp happens to feature one of the most prominent skeptics of all time: David Hume. During his lifetime, Hume's work was consistently denounced as works of skepticism and atheism. How did Hume arrive at his skeptical conclusions? Through what some would call his "radical empiricism". If the goal is to escape skepticism, do we really want to take the side of an empiricist, like Locke or Hume?

For those who are well-versed in contemporary psychology, you might notice that there are other problems with Locke's view that are empirical in nature (see Pinker 2002). However, given the time period we are covering, we should, for the moment, focus on philosophical objections about how this project apparently fails to help one escape from skepticism. The empirical objections will have to wait until the last lessons of the course. Stay tuned.

Moving forward

Now that you've been exposed to three competing approaches to knowledge available to you in the early modern period, which do you think is best? Let me rephrase that question. Had you lived through what someone living in the mid-17th century had lived through, which approach to knowledge do you think you'd prefer? Remember that we are jaded. We have 20/20 hindsight. We know how things are going to pan out. But if you were living at the time, my guess is that you would've sided with Descartes. Here are some reasons:

- Descartes and his rationalist/foundationalist project purports to be able to get us certainty, and this is very appealing. We have to remember that people were moving from the Aristotelian worldview, where objects were purpose-oriented and the Earth was the center of the universe(!), to a more mechanistic, cold, purpose-less Newtonian worldview. Humanity's self-esteem had taken a severe blow, and salvaging deductive certainty about the world seemed to at least be a comforting consolation prize.

- The Baconian empiricist movement was new and unproven. Sure there had been advances in astronomy, but these had the effect of putting science into a state of crisis more than anything. Thinkers, like Descartes, desperately sought to find foundations to replace the discarded old ones.

- Moreover, empiricism was suspicious. Locke's incapacity to ensure his readers that we really could know what the external world is like was worrisome. Later on, of course, Hume would use empiricism to lead us straight into the pit of skepticism. To many, empiricism didn't seem very welcoming.

And so, moving forward, we will further explore Descartes' rationalist/foundationalist project. The mere possibility of being able to achieve deductive certainty is extremely alluring. There is just one problem: Descartes uses God's existence as a means to escape skepticism. The next rational question is this: Does God actually exist?

Two approaches to scientific explanations were covered: teleological (goal-oriented or function-oriented) explanations and mechanistic explanations, which are goal-less, function-less, and purpose-less. The Aristotelian science that dominated Western thought for a thousand years was teleological. The universe was thought to be inherently teleological. The job of a natural scientist was to understand the teleological essences of categories of objects.

There were some unexpected social benefits associated with the downfall of the Aristotelian worldview.

There are various problems with Descartes' view, including concerns over his foundational truths not being very foundational and the perceived inability of his project to get us out of skepticism.

There is a division between two warring philosophical camps: rationalism and empiricism. The rationalists ground knowledge ultimately on reason, like Descartes. The empiricists, like Locke, use sensory experience as their starting point for acquiring knowledge.

Locke's view is distinguished from Descartes' in many ways, including Locke's reliance on the senses and his rejection of innate ideas.

Locke's view, however, also has its problems; most notably, it's hard to see how we can ever check that our representations of the world actually match the world itself (which seems just as bad as skepticism).

FYI

Suggested Reading: John Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding

-

Note: Read only chapters 1 and 2.

TL;DR: Crash Course, Locke, Berkeley, and Empiricism

Supplementary Material—

Related Material—

- Video: Closer to Truth, The Multiverse: What's Real?

Advanced Material—

-

Reading: Matt McCormick, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Immanuel Kant: Metaphysics.

-

Note: Most relevant are sections 1 and 2.

-

-

Reading: Peter Markie, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Entry on Rationalism vs. Empiricism

Footnotes

1. Castro at least would've had a good reason for wanting Kennedy dead. In chapter 18 of Legacy of Ashes, Tim Weiner (2008) reports that Kennedy seemed to have implicitly consented to assassination attempts on Fidel Castro, in order to repair his image after the Bay of Pigs disaster. There were dozens, maybe hundreds of attempts on Castro's life.

2. This discussion reminds me of the Metallica song "One" that describes the plight of a patient with locked-in syndrome.

3. The interested student can also take Dr. Leon's philosophy of religion class.