Seeing Justice Done

It is more necessary for the soul to be cured than the body;

for it is better to die than to live badly.

~Epictetus

On the fragility of social order

James C Scott's Against the Grain is, I believe, essential reading for anyone who wants to understand state-formation, the process by which a central authority amasses political domination over a given territory. First and foremost, Scott recognizes that the story of states is one told by states; as such, we should expect some bias in the narrative of history—a history whose writing has been sponsored by states. For example, there is a continual dismissal, denigration, and demonization of nomadic peoples. One of Scott's chief aims is to dispel the notion that early nomadic peoples were like a subspecies of humans. To even think of nomadic peoples as "less civilized" is, Scott argues, to accept the propaganda by the earliest states denigrating non-settled peoples. As it turns out, the growing animosity between the political elite of settled peoples and nomads can even be seen in different versions of the Epic of Gilgamesh. In an earlier version of the epic poem, the nomad character is just that: a nomad. In later versions, though, he is more savage and, for some reason, needs to have sex with a human female to be tamed and made more human. This denigration of the nomadic lifestyle, Scott argues, is all wrong.

Scott's Against the Grain.

In chapter 2 of Against the Grain, Scott details what happens to an animal species as it is being domesticated. He does this, he admits, with the aim of eventually arguing that our plants and our animals have, if you squint at the problem in a certain way, domesticated us. So here's what happens to a species as it is domesticated. Domesticated animals, relative to their wild counterparts, have reduced dimorphism. This is to say that the two sexes of the same species exhibit fewer and fewer differences besides their different sexual organs. In other words, the males and females of a domesticated species begin to look more and more alike. Also, domesticated species have a higher infant mortality rate, a greater reproduction rate, greater exposure to a disease pool, and are less capable of living outside of their ecological niche.

With these points in place, Scott muses about how these are all things that happened to humans as they transitioned from a nomadic existence to a sedentary one. Humans, Scott argues, are enslaved to their ecological environments, agricultural practices, and animals (both in the form of pets as well as in our animal agriculture). We spend an unsustainable amount of resources on these, as well as lots of time and energy. In fact, prior to the modern era, we would choreograph our whole daily and yearly lives to the needs of our animals and crops, which is why some of the oldest holidays tend to mark different stages of the planting cycle, e.g., Spring equinox, harvest time, etc. Today, home gardeners still labor away to make a utopian environment for their, say, potatoes.

Scott's most illuminating insight, though, might be his realization that the earliest states were shockingly fragile. As it turns out, the norm is that states collapse. In chapter 6, Scott details the various factors that could lead to state collapse, including pandemics, ecocide (e.g., resource depletion, salinization of the soil, soil exhaustion, etc.), population leakage (as when subjects abandon, or escape, from the state), and, of course, war with another state. Given Scott's conclusion that states actually decreased the quality of life of humans, he moves to make the case for normalizing collapse. Scott wagers that it may be that state collapse actually provided a respite from authoritarian control, an improvement in health, a more localized cultural life, and no significant drop in population. Indeed, he provides some scattered evidence of this. He speculates that state collapse is seen as a calamity in large part because researchers aren’t able to study non-state peoples as well, since there are, of course, no great city walls, artifacts are de-centralized, and languages become more fluid—and hence more difficult to study—without a central authority enforcing the use of some particular language.

Given that states were fragile and that their subjects tended to want to escape, i.e., state leakage, it is no surprise that the earliest states and the first multi-ethnic empires relied heavily on state terrorism to force their subjects to fall in line. That is to say that states had to scare their citizens into submitting to the existing social order, paying their taxes, and not escaping. It's hard to find a better example of this than in none other than the Roman Empire. For instance, consider the Third Servile War. This is when the famous gladiator/slave/general Spartacus led an army of over 100,000 slaves in rebellion. The details of the battles are not important for our purposes. What is important is how the rebellion ended. Once the slaves were defeated, the Roman elite had to ensure something like that wouldn't happen again. So they utilized a form of punishment that was meant specifically for enemies of the state: crucifixion. The Roman state crucified 6,000 slaves and displayed their bodies along Appian Way, the road that led to Rome. States, because of their fragility, have to police their subjects, and, when they break the rules and threaten the social order, they have to punish them.

Predict and surveil

Policing, as we've seen, appeared to be a necessary constituent of the earliest states. But even some societies of the ancient past have seen something undesirable about policing, even if it is not quite what some people today find morally objectionable about it. For example, the Greeks knew that policing was necessary, but they didn't want to police themselves. So, since during the Persian Wars many Scythians (nomadic horse archers that often served as mercenaries) were captured and taken into Athens as slaves, the Greeks tended to use them as civil police who would aid in forced voting as well as make arrests. Apparently, Greeks found performing those tasks themselves distasteful, considering the work to be more suited to barbarians than to their refined selves (see Cunliffe 2019, chapter 2).

There are many normative questions surrounding the issue of policing that could be covered here. For example, in his call for police abolition, Vitale (2017) points out various morally objectionable aspects of policing. He starts with their very inception. He argues that the basic nature of the law and the police is to be a tool for managing inequality and maintaining the status quo. In other words, inequality and asymmetrical power relations (where some have most of the power and others have very little or none) are built into the fabric of our social order; and the role of police has been to maintain that asymmetry. He argues that no police reforms could ever address this reality—only abolition would.

Even if one does not buy into Vitale's abolitionist argument, there are other aspects of policing that Vitale discusses that are morally objectionable from either consequentialist or deontological grounds. In chapter 10, Vitale (2017) stresses that the role of the police has repeatedly been to suppress dissident opinions, opinions that citizens of a free country have a right to express. Police, Vitale reminds us, began as a method of quelling labor unrest. More recently, in the 20th century, police targeted anarchists and communists, anti-war activists, civil rights leaders (such as Martin Luther King Jr and Malcolm X), and, even more recently, anti-police-violence groups, environmentalists, Muslims, Occupy Wall Street protesters, animal rights activists (who violate ag-gag rules), and even anti-death-penalty activists. Both federal agencies and the local police departments that help them are, one could argue, violating the categorical imperative, since they appear to not be enforcing the law impartially (but preferentially). Alternatively, one could argue that targeting protesters has the negative effect of not raising awareness about societal problems.

The topic of police abolition can't be done justice here. To fully flesh out this idea, it would be necessary to separate out the various tasks that police perform, discuss which ones are necessary and which ones are not, and figure out which institutions—whether they be already existing or new ones that would have to be created—could take up those tasks deemed necessary. All of this, of course, would require taking a careful look at reams of data from the social sciences. I hasten to add that some have done this, and they did not come to an agreement. Vitale, as we've seen, is for police abolition. Pinker (2013) is not (see especially chapter 2 of The better angels of our nature).

So here's a normative question we can discuss: What's a defensible hit rate? In other words, if we are provisionally accepting that policing is necessary, what is the appropriate ratio of convictions to the number of people the police actually stop (or surveil or arrest)? So, for example, if the police stop 100 people, but release 99 without charge and only arrest 1, that would be a 1% hit rate. Is this justifiable? How would you like to be one of the 99 who was stopped and questioned even though it was shown to be the case that you hadn't done anything wrong (or at least it can't be proved you had done something wrong)?2

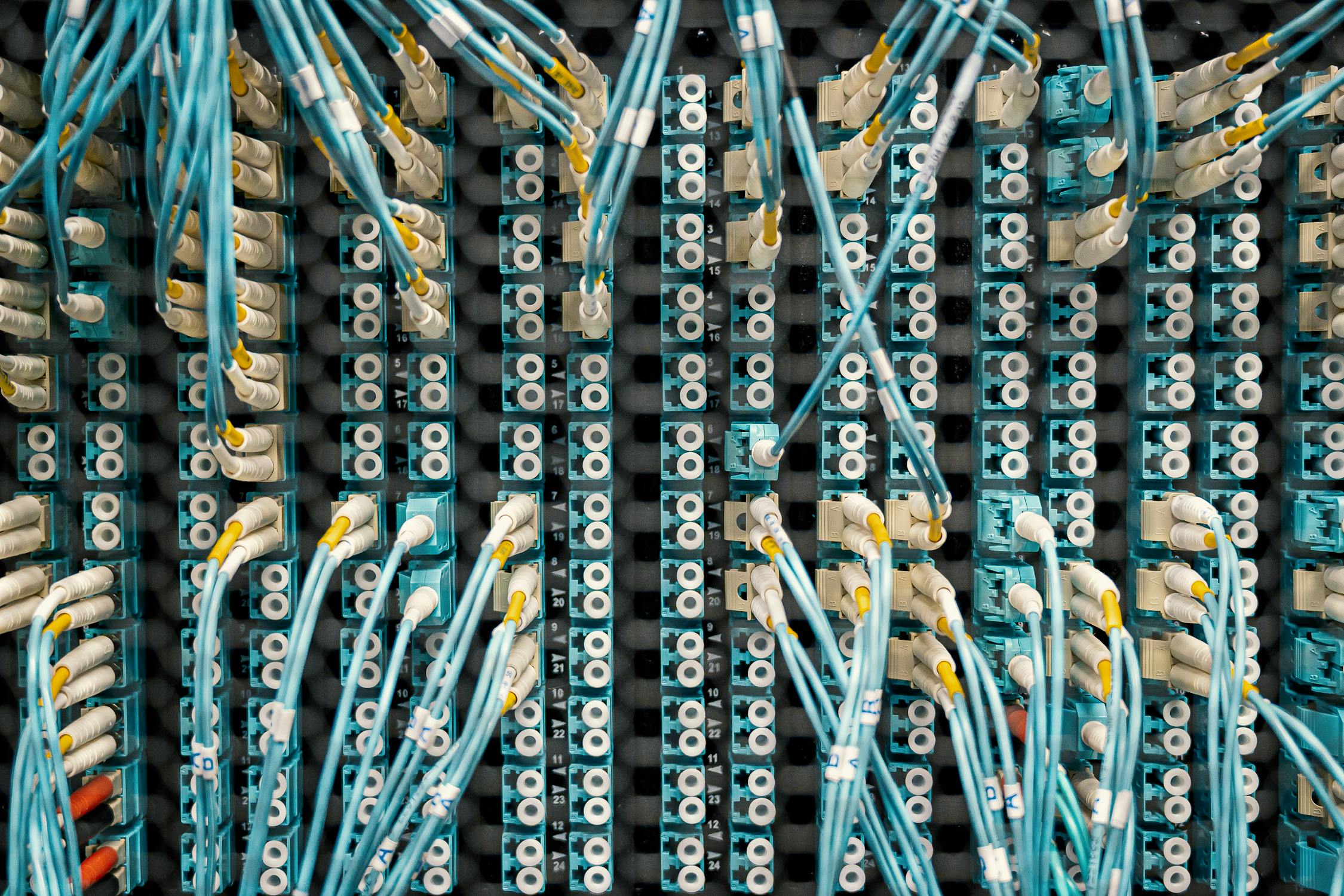

As we've seen, being impartial in enforcing the law is an important moral requirement. One recent trend towards making policing more objective is referred to as predictive policing, a concept pioneered by William Bratton right here in Los Angeles at the LAPD (Brayne 2020: 22). What is predictive policing? It is the use of machine learning and other computational methods for crime pattern recognition via the analysis of data from different databases (both public and private) available to law enforcement so as to guide the deployment of police officers. In short, it is automating certain aspects of law enforcement through Big Data. The idea is that, since the algorithms used are "just math", this approach to policing will be more objective than previous efforts.

In her recent Predict and Surveil, sociologist Sarah Brayne takes issue with the claims that predictive policing is actually more objective. Instead, she argues, we must recognize that data collection is itself sociologically influenced, and so the data collected might actually be biased, although this bias is techwashed away by talk of computational techniques and algorithms. For example, one method of data collection is through FI cards (Field Interview cards). These are generated through a point system in which chronic offenders are assigned a point value and ranked: five points for a violent crime, five points for a known gang affiliation, five points for prior arrests with a handgun, five points for being on parole, one point for every police contact (e.g., police stop), etc. This data is then input into one of the many databases that law enforcement agencies use when generating their predictions. But there is a clear problem here:

“On balance, the points system can quickly turn into a feedback loop and produce a ratchet effect wherein individuals with higher point values are more likely to be stopped, thus increasing their point value, justifying their increased surveillance, and making it more likely that they will be stopped again in the future... Moreover, the point system is not used in lower-crime areas of the city [Los Angeles]. Therefore, individuals living in low-income, minority areas like South LA have a higher probability of their 'risk' being quantified than those in more advantaged neighborhoods where the police are not conducting point-driven surveillance” (Brayne 2020: 69-70).

Overall, Brayne concludes that data-driven policing, at least as it is currently being practiced, is exasperating inequality in four different ways. The first is the ratchet effect which has already been discussed, which appears to be a algorithmic form of confirmation bias (ibid., 109). The second is that data-driven policing has led to the incorporating of non-criminals into police databases.

“Even if you do not consent to providing your information, by virtue of your network tie, you might be included in data systems. To be gathered up in what I call the 'secondary surveillance network', individuals do not need to have any police contact or have engaged in criminal activity; they simply need a data link to the central person of interest... [and] minority individuals and individuals in poor neighborhoods have a higher probability of being in this secondary surveillance net than those in higher-income neighborhoods” (Brayne 2020: 111).

The third way that data-driven policing exasperates inequality is through the phenomenon of false discovery in policing (i.e., false positives) and wrongful conviction. As Brayne reports, "Black people are seven times more likely than white people to be wrongly convicted of murder" (ibid., 113). Lastly, the fourth way data might exasperate inequality is that affected communities might be conditioned to avoid leaving digital traces. This means that they will avoid surveilling institutions like hospitals, banks, schools, and unions, hence suffering poorer health, less financial security, and and a lack of upward mobility (ibid., 114-15).

From a deontological perspective, it is easy to see that this bias is morally objectionable. The law is not being meted out impartially.

“Researchers have gained access and analyzed the magnitude of racial disparities in hit rates under stop-and-frisk [in NYC], finding that 80-90 percent of individuals were released without charge and hit rates were higher for whites than Blacks. Specifically, this confirmed that, controlling for precinct variables and race-specific baseline crime rates, Blacks and Hispanics were stopped more frequently than whites, even though whites who were stopped were more likely to be carrying weapons or contraband than were Blacks.” (Brayne 2020: 104).3

A consequentialist would also take objection to these, since there are measurable negative consequences to the aforementioned policies. Consequentialism, however, is always a little more complicated. In essence, if it could be shown that predictive policing could be improved to something like in the film Minority Report, it is unclear whether a consequentialist would object to the practice. This brings us to punishment...

Storytime!

"Blot him out"

Arguments against the death penalty

The LWOP alternative

It appears that roughly one in eleven of those currently on death row had a prior conviction of criminal homicide, per the US Bureau of Justice. Given this, it could be argued that had this one-tenth of the current death row inmates been executed, several hundred innocents would've never been killed. In other words, had the state executed offenders the first time around, they would've never gotten out and committed murder again, i.e., recidivism. But, there is no way to tell which tenth of prisoners convicted of criminal homicide will recidivate. It would be unreasonable, one could agree, to kill all of them knowing that only some will recidivate. So, the most rational approach is life imprisonment without parole (LWOP).

Too expensive

Research by several different investigators provides compelling evidence that the modern death penalty system in the USA is far more expensive than an alternative system of LWOP. This is due to the cost of trials, appeals, etc. Moreover, LWOP would mitigate recidivism as much as execution. So, capital punishment should be supplanted by LWOP (Bedau 2010: 727).

The risk of executing the innocent argument

During the 20th century in the USA, it is estimated that about 0.3 percent of executions were of innocent people. Although this is not a significant number, it is still a tragedy for the legal system. Moreover, LWOP could eliminate recidivism just as well as execution, as well as provide those who are wrongfully convicted with an opportunity to appeal (and not run the risk of being executed). So, as a protection for the innocent, capital punishment should be abolished.

Bedau's "best argument"

- Governments ought to use the least restrictive means—that is, the least severe, intrusive, violent methods of interference with personal liberty, privacy, and autonomy—sufficient to achieve compelling state interests.

- Reducing the volume and rate of criminal violence—especially murder—is a compelling state interest.

- The threat of severe punishment is a necessary means to that end.

- Long-term imprisonment is less severe and restrictive than the death penalty.

- Long-term imprisonment is sufficient to accomplish (2).

- Therefore, the death penalty—more restrictive, invasive, and severe than imprisonment—is unnecessary; it violates premise 1.

- Therefore, the death penalty ought to be abolished (Bedau 2010: 728-29).

Food for thought...

On what our descendants may think of us

There are various aspects of past societies that we look back on with horror. What comes to mind most easily for me is the Roman games, where humans and animals were slaughtered for the enjoyment of the crowds. But we need not go so far into the past. Even child labor conditions little over a century ago were horrifying. We like to think that the ban on child labor, to not say anything of Roman-style games, is a form of moral progress. But this leads to another question: What present-day practices will our descendants be horrified by? Some believe that the way we treat our criminals will be one thing our descendants will back upon with shame. Stanford neuroendocrinologist Robert Sapolsky feels this way:

“People in the future will look back at us as we do at purveyors of leeches and bloodletting and trepanation, as we look back at the fifteenth-century experts who spent their days condemning witches… those people in the future will consider us and think, ‘My God, the things they didn’t know then. The harm that they did’” (Sapolsky 2018: 608).

Sapolsky, in fact, goes further. He does not only believe that we should reform the criminal justice system to abolish capital punishment; he believes that some things that are currently considered crimes need to be reconsidered. This is not to say that the behaviors he discusses aren't dangerous and that humans who commit these shouldn't be sequestered. However, he does say that perhaps we should have some sympathy for certain people—people that can't help but to have horrible impulses.

“Writing under the provocative heading ‘Do pedophiles deserve sympathy?’ James Cantor of the University of Toronto reviewed the neurobiology of pedophilia. For example, it runs in families in ways suggesting genes play a role. Pedophiles have atypically high rates of brain injuries during childhood. There’s evidence of endocrine abnormalities during fetal life. Does this raise the possibility that a neurobiological die is cast, that some people are destined to be this way? Precisely. Cantor concludes, ‘One cannot choose to not be a pedophile’” (Sapolsky 2018: 597).

I don't want to weigh-in on this topic at this point. I present it more so to show you that intellectuals today are thinking critically about many aspects of society that we take for granted—that we assume will just continue to be the way they've always been. But some are agitating for change—not just for our imprisoned population, but for all those who are treated in inhumane ways. For example, animals...

An important normative consideration on the topic of policing is finding an acceptable hit rate, the rate at which a police-stop renders an arrest. Ideally, the hit rate should be high, so that you are only stopped when there is a high likelihood that you have actually committed or are involved in a crime. Low hit rates are associated with police states, where everyone (or nearly everyone) is surveilled regularly. Sociologist Sarah Brayne, however, reports that current policing methods are disproportionately targeting minorities. This is even the case with predictive policing, which she argues is just an algorithmic form of confirmation bias, at least in the way that it is currently being practiced. This leads to both deontological and consequentialist worries that policing is currently being done in a morally problematic way.

With regards to capital punishment, there are various arguments for the practice, including van de Haag's argument about instilling fear in criminals, Bern's argument that capital punishment alleviates the anger that arises from criminal activity and restores dignity to the law, Mill and Bentham's incapacitation and determent arguments (where it is assumed that capital punishment will reduce crime, i.e., a positive consequence), and Kant's retributivist argument (where it is assumed that criminal activity deserves punishment and it is right to provide this punishment, preferably in a way that "fits" the crime).

There are various arguments against capital punishment, including the claim that life imprisonment without parole is more rational, either because it is less expensive or because we don't run the risk of executing the innocent. There is also Bedau's argument that the state should be as unintrusive as possible when pursuing state goals (like reducing crimes); Bedau argues that life imprisonment without parole is optimal for this end.

FYI

Suggested Reading: Anton Chekhov, The Bet

Supplementary Material—

Reading: John Stuart Mill, Use of the Death Penalty

Related Material—

Audio: NPR, All Things Considered, Botched Lethal Injection Executions Reignite Death Penalty Debate

Short Story: Franz Kafka, In the Penal Colony

Podcast: Dan Carlin’s Hardcore History, Painfotainment

Footnotes

1. Scythians were also objects of derision. For example, being called a descendant of a Scythian was a political insult (see Cunliffe 2019, chapter 2).

2. It's important to note that the lower a hit rate is the closer that society is to something like a police state. In other words, if police work is more like just stopping everyone and seeing who's guilty of something (a low hit rate) than doing actual police work and only questioning likely suspects (a high hit rate), then one could argue that low hit rate societies are less free than high hit rate societies, since in low hit rate societies surveillance is the norm.

3. Researchers have not been able to get access to data necessary to conduct a similar analysis in Los Angeles (Brayne 2020: 104).