Self-less

You only lose what you cling to.

~Siddhartha Gautama

Important Concepts

Origins

Awakening

Upon enlightenment, Buddha realized that duḥkha is ever-present in our lives; we live perpetually in a condition of dissatisfaction. Buddha realized that in our natural state, our lives are permeated with desires. We also have a desire to fulfill our desires (taṇhā). And so we are constantly searching for ways to fulfill our desires. But it's always the case that as soon as we fulfill one desire another one arises. Our quest for fulfillment is never completed. We spend our lives endlessly trying to quench our desires.

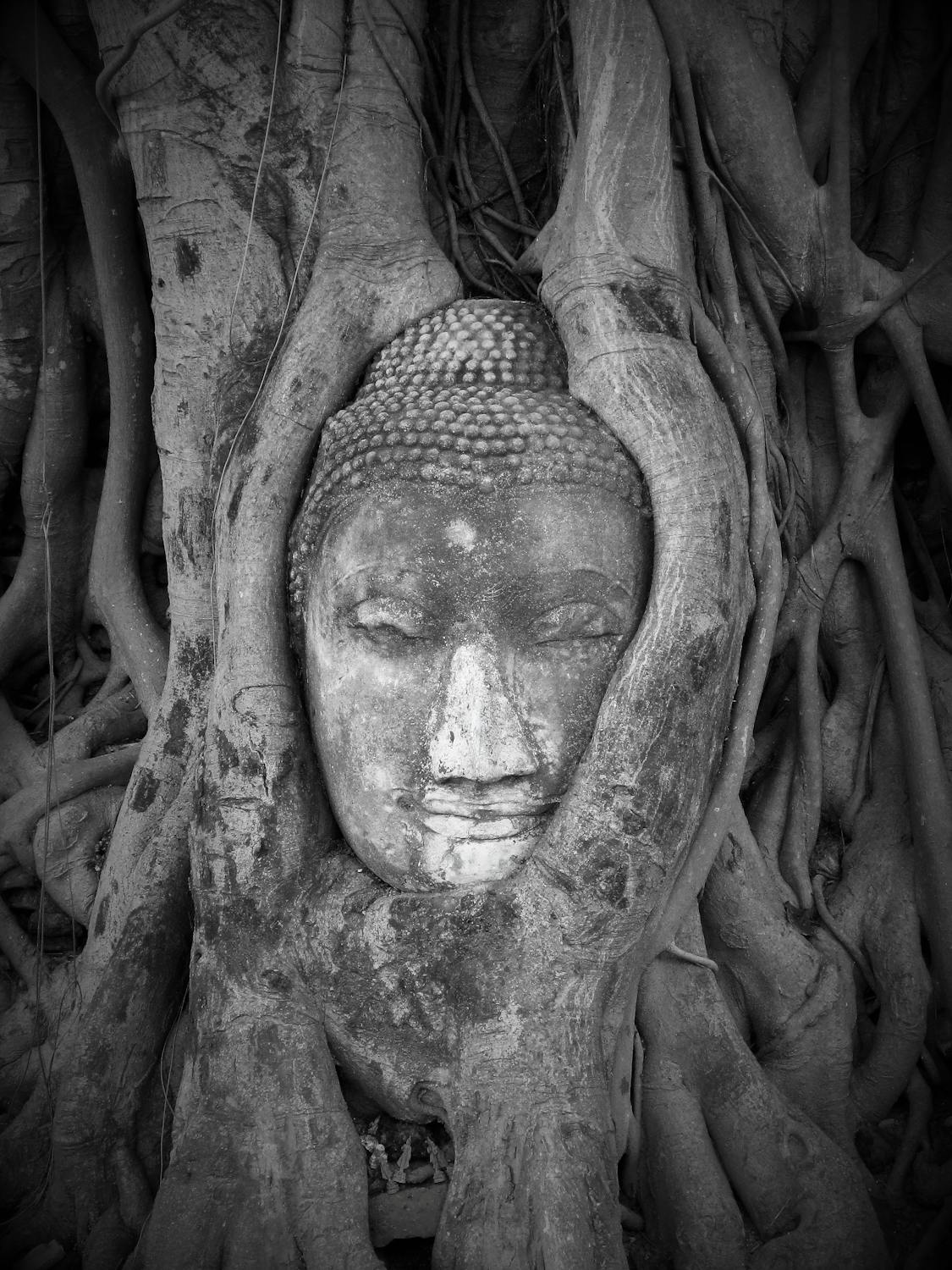

A person, perhaps

in the grip of duḥkha.

Let's take a modern-day example to make this more real. You are, at this moment, studying and working towards completing this course. You are most likely doing this because acquiring a college degree is important to you, and you want to be able to pursue a meaningful career after graduation. This is all to say that you have a desire to complete this course, complete your studies, and start your career. Let's just say you accomplish all those feats. Are you finally rid of desire? Not at all. Next come the stresses of work-life. Perhaps you want to advance in status or get a raise; maybe you want to balance your time at work with your family-life. This just means that you have more desires: a desire for more status, more money, more time to spend with your family. Will you finally be satisfied when you get more status, more money, and more time with your family. Almost definitely not. You will spend much effort maintaining this position. You will have a desire to keep what you have. Perhaps on a more psychological note, it may be the case that once you enjoy some success, your desire for success will grow. You don't merely want to keep your position; you'll want more.

In this example, we are only considering the major components of your life: schooling, career, family. If you think about it, though, you will realize that even your day-to-day existence is just one desire after another. You desire to stay in bed. You desire to skip class. You desire food, sex, money. And when you don't fulfill these desires, you're left with the subjective feeling that something is off. And even if you do fulfill these desires, more desires will follow, so that you're never content. You are never truly satisfied. There's always something else. It never ends.

Going back to Buddha, Buddha realized that the cause of this is our desire to fulfill our desires (taṇhā). If we could just stop trying to fulfill all of our desires, we would be satisfied. We would no longer be troubled. We can just witness and accept that we have desires, but we won't be slaves to the never-ending cycle of trying to fulfill our desires. We would thus be released from this form of bondage. Buddha summarized his philosophy in The Four Noble Truths.

- The truth of suffering: All life is duḥkha.

- The truth of the cause of suffering: Duḥkha is caused by taṇhā.

- The truth of the end of suffering: The cessation of duḥkha is possible, ie nirvana.

- The truth of the path that frees us from suffering: The way to accomplish this is the Eightfold Path.

The Eightfold Path

- Right View- Buddha recommends that you do your best to see the world as it is. In other words, realize the Four Noble Truths.

- Right Intention- Once you've reached the right view, dedicate your life to helping yourself (and others) reach enlightenment in whatever way you can.

- Right Speech- Controlling your speech acts is one of the most straightforward ways you can work towards enlightenment. Do not hurt feelings, do not lie, do not use deceptive or intentionally confusing language, do not intentionally make people angry with your speech.

- Right Action- Move on to your non-verbal behaviors and make sure your actions go towards helping and not harming.

- Right Livelihood- Make sure what you do for a living is not causing suffering, but rather that it is helping others.

- Right Effort- Make a continued effort to devote your waking energies towards the liberation of yourself and others.

- Right Mindfulness- Make a continued effort of being present, living in the here and now (as opposed to living with regrets or neglecting those in front of you (for example, by spending too much time on your phone!)).

- Right Concentration- Practice meditation diligently.

No Self

So what happens if you live the Eightfold Path diligently? The Buddha claimed that you will eventually reach enlightenment. Enlightenment occurs when one awakens to the realization that there is no self; in other words, it's when you realize the self is just an illusion. To be clear, Buddha is not denying that you have a body. Limbs, organs, skin and nails all exist. Instead, he's arguing that whatever the word "I" refers to (when you say it) is an illusion.

Let's think about this a bit (in the first person). I am not my body, since my body does all sorts of things that I don't do: process my food, regulate my sleep cycle, beat my heart, etc. Or is it the case that I actually will those things to happen? It doesn't seem like it. So I'm not my body. Am I my brain? This seems unlikely too. My brain also does many things that I don't consciously do. To take one example, I don't process the input from my eyes. In fact, I passively receive the output from my visual cortex. It's almost like I'm in a theater, relaxing, allowing my brain to process data from my senses and I just receive the output. So then what do I really do? I don't even manufacture my desires, since those seem to arise independent of me. In fact, sometimes I wish I didn't have, say, my desire to sleep in. Instead, it seems like I'm also a passive recipient of my desires. I don't seem to do much of anything. The Buddha argues that this is because the "I" is an illusion (see Siderits 2007, chapter 3).

This might seem far-fetched at first... But the idea receives some backing from modern science, in particular neuroscience and psychology. For example, neuroscientist Lisa Feldman-Barrett, whom we've met before, explicitly affirms it:

“The fiction of the self, paralleling the Buddhist idea, is that you have some enduring essence that makes you who you are. You do not. I speculate that your self is constructed anew in every moment by the same predictive core systems, including our familiar pair of networks (interoceptive and control), among others, as they categorize the continuous stream of sensations from your body and the world” (Barrett 2017: 191-2; see pages 190-194 for a general discussion).

Similarly, the dual-process theory of psychologist Daniel Kahneman, whom we've also met before, strongly lends itself to a Buddhist interpretation:

“You do not believe that these results apply to you because they correspond to nothing in your subjective experience. But your subjective experience consists largely of the story that your system 2 [your higher-cognitive faculties] tells itself about what is going on. Priming phenomena arise in system 1 [the automatic, emotion-based system], and you have no conscious access to them” (Kahneman 2011: 57; interpolations are mine; emphasis added).

In other words, Kahneman is saying that your subjective experience of yourself and the world is "largely" just a story that your system 2 tells itself. However, recall that system 2 doesn't call the shots—system 1 is usually in charge. And so this story is more fabrication than anything else.

Perhaps psychologist Bruce Hood puts the point more forcefully:1

Eastern Thought

and the Problem of Evil

Buddhists, like Christians, are very concerned with unnecessary suffering. Buddhists argue that humans are full of desire as well as the desire to fulfill their desires (taṇhā). As such, they are attached to material objects. This leads to war, fighting, greediness, stealing, and the like. But with liberation, humans will be free of desire. And hence, human wickedness will stop. That is how Buddhists plan on addressing unnecessary suffering. But can Eastern Thought solve the Problem of Evil? This is Dilemma #10.

The Yin/Yang Symbol.

As I mentioned in The Problem of Evil (Pt. II), students often attempt to respond to the Problem of Evil with use of some Eastern concepts, like that of Yin/Yang or Karma. For example, some students argue that unnecessary suffering only appears to be unnecessary, but it is actually the case that you can't have goodness without suffering (Yin/Yang). They've also argued that what appears to be unnecessary suffering could be the universe punishing that person/animal for the past wrong they've done (Law of Karma).

However, I'm not sure that Eastern Thought can help theists who are attempting to solve the Problem of Evil, or at least not Buddhism. Buddhism, at least in its original philosophical form, is a non-theistic worldview (see Siderits 2007: 6-7). They do not have a God. In fact, some people deny Buddhism is even a religion, and argue that it is more like a philosophy of life. It seems, then, that the Problem of Evil would never arise for them in the first place.

But the argument in the preceding paragraph only makes the case that Buddhists wouldn't need to address the Problem of Evil as we've been dealing with it. I have not argued that Eastern Thought can't help solve D#10. I will do that now. Here's are the basic problems I will cover:

The Yin/Yang Paradox

Can God create moral goodness without moral wrongness? Good without evil? Pleasure without pain? If He can’t, then He’s not all-powerful. If He can, then He’s not all-loving (since He didn’t).

The Karma Paradox

If someone claims that the notion of karma helps solve the Problem of Evil, this only raises more questions. Why should we believe the Law of Karma even exists? If suffering is a result of karma, why doesn’t God ameliorate it, since God is omnipotent? What's the point of hell, then? Is God bound to the Law of Karma? If He is, then He's not all-powerful. But how would we know anyway?

I further discuss all of this below...

The founding Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama, argued that duḥkha, the subjective feeling that a basic and important aspect of our lives isn’t right, permeates throughout our lives; we live perpetually in a condition of dissatisfaction. The Buddha realized that, in our natural state, we are full of desire as well as the desire to fulfill our desires (taṇhā). He concluded that the path to liberation from duḥkha requires that we stop trying to fulfill all of our desires; only then would we be satisfied.

One of the most interesting aspects of Buddhist philosophy, which is backed by modern psychology and neuroscience, is the view that there is no robust self; i.e., that our sense of self is an illusion, a fiction that is fabricated by our brain.

Buddhism, at least in its early stages, was a non-theistic religion. This means that they did not have a god—Siddhartha never claimed to be a god. This means that there is no all-powerful, all-loving, all-knowing being in their philosophy, and so the problem of evil would never arise for them in the first place.

Even if one were to try to integrate concepts from Eastern Thought into the Western tradition, it is not clear how they would fit in. For example, what is the relationship between God and the law of Karma? Is God bound by the law of Karma? Did God create it? Are they co-equal? Why isn't the law of Karma mentioned in any Judeo-Christian sacred texts? In short, there are more questions than answers.

FYI

Suggested Reading: Mark Siderits, Buddhism as Philosophy: An Introduction, Chapter 2

-

Note: This PDF includes chapters 2 and 3. Only chapter 2 is the suggested reading, but some students may also have interest in chapter 3.

TL;DR: Crash Course, Buddha and Ashoka

Supplemental Material—

- Video: School of Thought, Eastern Philosophy | The Buddha

- Reading: Mark Siderits, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Entry on Buddha

Related Material—

- Video: Big Think, Sam Harris: The Self is an Illusion

Advanced Material—

-

Reading: Thomas Metzinger, The No-Self Alternative

-

Reading: Olaf Blanke and Thomas Metzinger, Full-body illusions and minimal phenomenal selfhood

-

Book: Mark Siderits, Buddhism as Philosophy

Footnotes

1. The interested student can take a closer look at Hood's work through his (2012) The Self Illusion.