Stability

Whoever is careless with the truth in small matters cannot be trusted with important matters.

~Albert Einstein

Important Concepts

Knowledge and opinion

Last time, we considered the distinction between empirical claims and non-empirical claims. The main point was to make sure you keep track of what is an empirical claim and what is not, since empirical claims have their own ways of being assessed: either through direct sensory experience or through the process of science. Today we will considered a closely-related distinction: that between knowledge and opinion. I tend to save the finer distinctions of the study of knowledge (known formally as epistemology) for my PHIL 101 course. However, what we can say is this: it is generally accepted that you can only have knowledge about claims that are either true or false. Claims that are either true or false, by the way, have a special name; they're said to be truth-functional. Truth-functional sentences seem to be best expressed as declarative sentences, i.e., sentences that describe some state of affairs, like "Misha is over six feet tall" and "Bianca double-majored in psychology and biology". This is contrast with sentences that take the form of questions or commands; questions and commands seem to not be truth-functional. In other words, it seems to be a misapplication of the concept of truth if you were to label a question as true. For example, if I were to ask you, "Where is your homework?" and you were to respond with "The sentence you just said is true", then everyone listening would suspect that you don't know how to appropriately use the label of truth. It just seems like that you don't use that label on questions. One other thing! It's easier to discuss these truth-functional declarative sentences if we give a name to the thought that is expressed by these sentences. Philosophers have done just that. The thought behind a declarative sentence is called a proposition. In short, it appears that you can only know propositions, which come in the form of declarative sentences (since only declarative sentences are truth-functional).

Avant-garde jazz trio

The Bad Plus.

On the other hand, there are sentences that hold content which is not the kind of thing you can know, since the claim embedded in the content doesn't seem to be truth-functional. For example, if you were to say "Polyrhythmic jazz is the best kind of music ever", then it's pretty clear you're expressing an opinion. Opinions like these can sometimes be interpreted as a proposition. In other words, one might interpret that sentence as saying that there's such a thing as the property of being the best kind of music ever, just like some objects have the property of being blue or the property of weighing more than five pounds, and that polyrhythmic jazz has this property. But of course, it seems like the property of being the best kind of music ever is completely made up. It certainly doesn't seem to exist in nature independent of the minds of humans; it is mind-dependent. So, even if someone says, "I know that polyrhythmic jazz is the best kind of music ever", we're not really taking them to mean that they have some sort of knowledge about what the best kind of music ever is. Instead, we'll interpret them as expressing that they feel really good about saying that polyrhythmic jazz is pretty awesome.1

So there's claims that are truth-functional, and these (if they're actually true) seem to have a truth-maker—they correspond to the world in the sense that there something that exists in the world that makes the proposition true. You can actually know these. Other claims appear to not be truth-functional, but are instead expressions of emotion, or personal preferences, or of strongly-held convictions. This second group we can call opinions. Here's the tricky part, though. Where do we draw the line?

Randy Firestone.

In his book Critical Thinking and Persuasive Argumentation, Randy Firestone argues that the only facts that you can know are those that are ultimately rooted in sensory evidence, everything from that which you checked with your own sensory organs to the products of the systematic observations of communities of scientists—and that ain't nothing. But he makes the case that claims in ethics and metaphysics are simply beyond what any rational person can call "facts". For example, how can one demonstrate that the sentence "Spanking your children is morally abhorrent" is a sentence that actually has a truth-maker somewhere in the world? This is not to say that spanking children is permissible, by the way. What Firestone is saying is that there's no sensory information that could confirm (or disconfirm) the sentence "Spanking your children is morally abhorrent". So, Firestone argues, most ethical claims are best construed as opinions, true only relative to the person saying them.2

On the other hand, in his lectures on critical thinking, Mark Balaguer appears to not be comfortable drawing the line between facts and opinion where Firestone drew it. Balaguer believes that the view that some ethical claims are best construed as opinions is "controversial" at best (see chapter 9 of Balaguer 2016). This is to say that it is not clear that it is true. Balaguer instead opts for not discussing ethical claims at all, leaving it up to the reader to decide for themselves whether moral judgments are best thought of as truth-functional claims or as expressions of emotion and subjective preference.3

So drawing the demarcation line between fact and opinion is hard. Nonetheless, critical thinkers should note that a. there are some claims that are clearly truth-functional, and b. there are some claims that are clearly opinions. In the middle you might run into some problems, of course. My advice, then, is to try to always steer your investigations towards what is clearly truth-functional. In other words, if you are getting bogged down in metaphysical and/or ethical debate, then just steer the conversation towards what can actually be verified through the senses. You might not end up with the same questions you started with, but the pivot away from claims that are not empirically-tractable will pay dividends.4

Argument Extraction

Pressure release

Occupy protesters.

Should we take Plato's apparent advice seriously? Should we try to unify society into a coherent whole as much as possible? Should we emphasize our similarities rather than our differences? If we do so, will there be greater stability?

With regards to wealth, it does seem like wealth inequality is driving a wedge in American society. This is part of the reason why tens of thousands participated in the Occupy Wall Street protests which started in September of 2011. Their slogan "We are the 99%" was rallying cry to all those who felt that income and wealth inequality had grown to be unsustainable and unacceptable. As it turns out, it was not only New Yorkers who felt this way. Occupy Wall Street grew into the Occupy Movement more generally and dozens of cities around the country broke out in protest. In Plato's words, the USA had become two cities: one composed of the one percent and the other made up of the rest. And it was clearly the case that tensions were high. It didn't matter that the sitting president was a Democrat. It didn't matter that there was no real plan being given by the movement for how to move forward. According to one survey, a sizable chunk (35%) of Americans supported the movement—property damage and all. A country divided indeed. Here's some Food for thought...

Perhaps there's something that can be done, however, as a sort of a "pressure release". Some political candidates have recently advocated for a universal basic income, where everyone gets enough to meet some basic needs, to address income inequality. That's one option. Presumably having a guaranteed income will provide a safety net so that no one lives in abject poverty and feels the need to protest for months on end. Here's another idea. Kai-fu Lee (2018, chapter 9) lays out his vision of a social investment stipend. The universal basic income, Lee argues, will only handle bare minimum necessities but will do nothing to assuage the loss of meaning and social cohesion that will come from a jobless economy as more and more jobs get automated and/or otherwise robotized. (Stay tuned.) This is where Lee's social investment stipend comes in. These stipends can be awarded to compassionate healthcare workers, teachers, artists, students who record oral histories from the elderly, the service sector, botanists who explain indigenous flora and fauna to visitors, etc. By promoting and raising the social status of those that promote social cohesion and emphasize human empathy, Lee argues we can build an empathy-based, post-capitalist economy. Plato might like that one. Or else... What's the alternative?

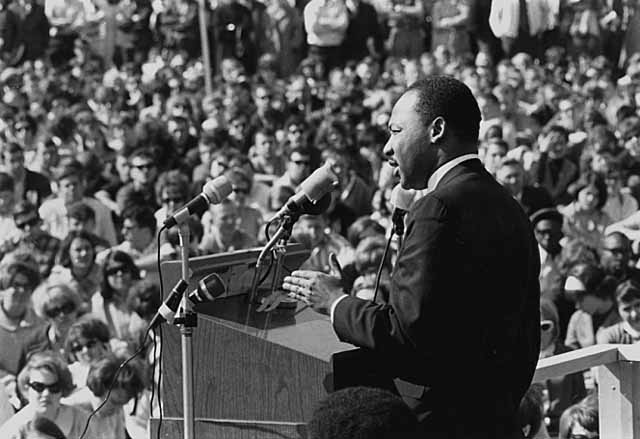

Martin Luther King, Jr.

There's another dimension of American society that seems to be the source of tension, and just talking about this one can get me in trouble(!). Let's be honest. Racial relations have never been smooth in the USA. It's been less than rosy forever, basically. I hope we can agree on that. What many are not agreeing on now, however, is how to move forward. One civil rights leader from the middle of the 20th century made the case that who we are is fundamentally rooted in our character and in our actions. We are more than just our skin color—and perhaps we can add gender, sexual orientation, and whether or not we are persons with a disability. This civil rights leader is, of course, Martin Luther King Jr., and you probably remember this line from his most famous speech. "I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character." Let's call this the character view: who you are is a function of your character. However, there's also been a current of thought (also going back to the 20th century) that stresses that who we are is fundamentally linked to our race, gender, sexual orientation, etc. Some (e.g., Murray 2019) call this approach, along with the resulting political mobilization, identity politics.

If we are taking Plato's advice seriously, then identity politics definitely has to go. This is because identity politics, by its very nature, atomizes society into interest groups (e.g., the LGBTQ+ community, women, African Americans, etc.). This is clearly the opposite of "one city". You might say that these interest groups are marginalized and oppressed, and thus need some sort of cohesive movement to help them overcome their social chains. But some (e.g., Murray 2019, Mac Donald 2018) argue that identity politics is not only ineffective, but that it has been causing discord at our universities and lowering the quality of the content in our shared intellectual spaces. Note that beginning in 2014, there was an increase in student demands that controversial speakers be uninvited to speak at their university (even though, as Murray reminds us, attendance was optional). There were also more instances of students shouting down speakers, and there were demands for "safe spaces", "trigger warnings", and regulating of "violent speech" (Lukianoff and Haidt 2019). There were student takeovers of some colleges. Some teachers were fired while others felt compelled to resign (along with their spouses). It's even the case that some professors were injured.

Professor of Political

Science Allison Stanger,

who suffered a neck

injury during a protest.

What's going on here? To some, this is a healthy expression of our first amendment rights. However, thinkers like the the ones mentioned in the previous paragraph are alarmed that the university is not being able to perform its function, and they blame it on the growing role that identity politics plays in the minds of students. For example, British author Douglas Murray is concerned that the rise of identity politics has distorted not only education but even the media. In his The Madness of Crowds, Murray reminds us of what utilitarian philosopher and member of Parliament John Stuart Mill said in On Liberty: that we should listen to the views of others, even if we disagree, because they might be partially right (and we can thus learn from them). Obviously, though, shutting down speakers does not allow students to learn anything from speakers (who probably have at least some good points that we can all consider). Furthermore, Murray makes the case that it is making our media environment (even) less informative. Murray argues that the media panders to those who advocate identity politics, making the news less informative as a whole. One domain that he focuses on is how even inconsequential news about LGBTQ+ community makes headline news, bumping off other news stories from the broadcast. One telling example is when a Japanese c-list celebrity came out as gay, and then this news event overshadowed a true tragedy that was occuring at the same time: a natural disaster in Indonesia which killed thousands. It is important to note that Murray, who himself is gay, is not attempting to minimize the plight of the LGBTQ+ community; but he does want it to be put in perspective. Japan, he argues, is not a particularly anti-gay community; Japanese people appear to be generally apathetic about the whole issue. In other words, ideally, the news story about a gay actor (that most people don't know about) shouldn't bump the actual news of a natural disaster elsewhere in Asia. But it did. And it is this kind of thinking, Murray argues, that is not allowing some universities and the media to function properly.

Psychologist Jonathan Haidt's explanation is a little more nuanced. In a recent interview, Haidt first noted that social media plays an important role in the psychological lives of young people. He points out how disanalogous social media is from normal social-communicative venues (i.e., regular communication). In social media, you are publishing for the benefit of a non-general audience (who are actually selected for via algorithms for like-mindedness and are more likely to be the kind of people that are on social media long enough to see your post and who give immediate approval or disapproval). As such, your interactions are inauthentic and forced. You say things merely to get approval. This creates a spiral into normative poles. In other words, you are more like to simply "perform" and say things exclusively for your base—the left, the right, whatever.

It gets more complicated, though. Recall the lesson titled A Certain Sort of Story. In it, we learned that the only currency in social media is attention. So, any subculture that arises out of social media is going to see attention as an intrinsic good, as opposed to, say, truth. This can be seen in call-out culture. A typical strategy of call-out culture is to hinge on one word (or phrase) and interpret it in the worst possible way, not taking intent into consideration at all. The person who called out the “offender” out gets the prestige for identifying a bigot or racist or whatever. Note that this doesn’t require an assessment or discussion about any actual offense; the person who called out the offender gets credit for every call out, regardless of whether or not they called out someone who is actually racist, or bigoted or whatever. It's like getting paid for every bullet you shoot, not every target you hit. This is all, of course, usually accompanied by demands to have the offender fired from their post. Haidt argues that this practice, far from protecting disenfranchised groups, actually leads to making oneself more susceptible to feeling marginalized and feeling targeted more often; it gives negative emotional power to words that would otherwise be benign. It makes you feel like the world is more hostile than it really is. This is part of the reason why Gen-Z has higher rates of depression (although paranoid parenting probably didn't help; see Levine and Levine 2016). See Haidt and Lukianoff's The Coddling of the American Mind for more.

Is it true that the kind of thinking that fuels identity politics (enabled by social media) is making our universities dysfunctional? Is the function of a university social justice or the pursuit of truth? Does identity politics actually move us closer to social justice or does it just divide us even more? What is to be done?

- Read from 419a-430c (p. 103-115) of Republic.

Although the demarcation point is fuzzy, it's important to distinguish between facts (which are truth-functional) and opinions (which are expressions of emotion or subjective preference).

In today's reading from Republic, the characters note that cities that are not well-governed are fractious, its constituent parts warring with each other. They also note that in their perfect city, they have found the virtues of wisdom and courage—wisdom in the Guardians and courage in the auxiliaries.

The dialogue today prompted us to consider aspects of society that might lead to internal divisions, such as massive wealth/income inequality and divisive politics.

FYI

Suggested reading: Jonathan Haidt and Tobias Rose-Stockwell, The Dark Psychology of Social Networks

TL;DR: Jonathan Haidt, Lecture on The Coddling of the American Mind

Footnotes

1. Polyrhythmic jazz is pretty awesome, by the way. Check out As This Moment Slips Away by The Bad Plus.

2. Notice that I said "most" when describing Firestone's views on ethics. He actually has a mixed view in the sense that he believes that some moral judgments are objectively true, like "Murder is wrong", but others are only subjectively true, which is a form of relativism.

3. I side more so with Firestone than with Balaguer. Following the historical work of Alasdair MacIntyre (2003, 2013), I tend to agree that phrases like "morally right" and "morally wrong" don't seem to mean anything at all anymore. There used to be a fixed meaning, argues MacIntyre, but that was lost ages ago, and we now live in a kind of linguistic anarchy when it comes to moral terms. This is not to say that I'm a relativist, as in Firestone's mixed view (see Footnote 2). Instead, philosophers generally refer to my view as radical moral skepticism; the interested student should take my PHIL 103 course.

4. Some students ask what the difference is between the distinction between empirical and non-empirical and the distinction between facts and opinions. The long and short of it is that some facts are not empirical. This is because some sentences that are clearly truth-functional are true not by virtue of anything that the sentence corresponds to in the real world, but in virtue of the logical words inside the claim. In other words, there are some true sentences that are just logically true, like "Either I am a banana or I am not a banana". This sentence might not be terribly enlightening but, if you think about it, it's impossible for this sentence to be false. That, obviously, means it's true. More importantly for our purposes, however, it is true regardless of what the world is like. So, it is a true sentence whose truth does not hinge on any empirical observation. Thus, the distinctions between the empirical/non-empirical and facts/opinions are not one-to-one; they are two different distinctions.