The City of Words

Trust but control.

~Soviet Era Proverb1

Breaking News!

The City of Words

The primary task of this course is similar to the thought-experiment that Socrates and company explored in Plato’s Republic. In this classic by Plato, the characters in the dialogue attempt to understand the nature of justice by building a "city of words", an ideal city that functions optimally. The purpose of this exercise is to see when exactly justice enters the picture. Put differently, they discussed an imaginary city, engineered it so that it operates in an ideal way, and then tried to figure out where justice is in this perfect society. This is, in a round-about way, sort of what we'll be doing. This is to say that by enrolling in this course, you are now part of a council which will decide on the policies that will be enacted in the newly autonomous region of Ninewells, a territory just north of the state of Montana. This is a region that was erroneously awarded to British North America—now Canada—in the aftermath of the War of 1812 (due to poorly-drawn maps). The region has been in political limbo for some time, but now we've been given the opportunity to come up with a constitution for the territory. We will call our little group the Council of the 27. The Council of the 27 will decide on social issues such as:

- what form of government should be utilized?

- what economic policies should be implemented?

- what should the educational system look like?

- what regulations (if any) should be put on industry?

- what technologies should be regulated and/or banned?

- whether or not being a parent should require a license?

In order to perform your function well, members of the Council will have to become proficient in the analysis of arguments and the language used within them, the evaluation of evidence, and the capacity to discriminate between different epistemic sources, i.e., discern between good sources of information and bad ones. To this end, I introduce the following Important Concepts in order to begin the required training. In the rest of this section I will make some additional points about the important concepts, we'll look at some Food for Thought, we'll discuss a cognitive bias that might get in the way of good reasoning, and then we will begin to cover the arguments of Plato's Republic—the primary training resource for this course. We will read this work in its entirety, by the way. And so, without further ado, the training begins now.

Important Concepts

Some comments

Napoleon III, the

last French monarch.

Logical consistency is a cornerstone of critical thinking. For a set of sentences to be logically consistent only means that it's possible that all the sentences in the set are true at the same time. It's not that they actually are true, but just that they can all be true at the same time. That's it. But even though logically consistency seems like a very low bar, it is absolutely essential to be logically consistent when thinking rigorously about the world. For example, if one is trying to explain some phenomenon (e.g., migration patterns), one should make sure that one part of one's explanation doesn't directly contradict another part of the explanation. This seems easy enough in uncomplicated theories. Unfortunatley, though, most phenomena that needs explaining can't be explained by uncomplicated theories. And sometimes it is hard to see how two parts of a theory are inconsistent with each other when the theory has lots of moving parts. To make matters worse, there is a tendency to equate consistency with truth; but they are not the same thing. This is because two statements can be consistent with each other despite them both being false. For example, here are two sentences.

- "The present King of France is bald."

- "Baldness is inherited from your mother's side of the family."

"The present King of France is bald" is false. This is because there is no king of France. Nonetheless, these sentences are logically consistent. In other words, they can both be true at the same time; it just happens to be the case that they're not both true.2

Arguments will also be central to this class. Arguments in this class, however, will not be heated exchanges like the kind that couples have in the middle of an IKEA showroom. In this class, we will consider arguments to just be piles of sentences that are meant to support another sentence, i.e., the conclusion.

As you learned in the Important Concepts there are two major divisions to logic: the formal and informal branches. In this class, we will be focusing on informal logic. There are other classes that focus more on the formal aspect of argumentation, such as PHIL 106: Introduction to Symbolic Logic. Classes like this one instead focus on the analysis of language and the critical evaluation of arguments in everyday (natural) languages. One aspect of these classes that students tend to enjoy is the study of informal fallacies. Here's your first one:

Informal fallacies like argumentum ad hominem, are surprisingly easy to fall prey to. If one isn't keen, placing the argument into numbered form—sometimes called standard form—then one might not notice that the connection between premises and conclusion is insubstantial. In general, we will attempt to place all arguments into standard form. This way we can evaluate each individual premise for truth, i.e., check if the evidence assumed is actually true, as well as assess the relationship between premises and conclusion. You'll get a better idea of why using standard form reliably is a good idea in the Food for Thought below. Then you'll learn about why it's easy to fall prey to informal fallacies in the Cognitive Bias of the Day.

Food for Thought...

Cognitive Biases

For evolutionary reasons, our cognition has built-in cognitive biases (see Mercier and Sperber 2017). These biases are wide-ranging and can affect our information processing in many ways. Most relevant to our task in this course is the confirmation bias—although we will definitely cover other biases. Confirmation bias is our tendency to seek, interpret, or selectively recall information in a way that confirms our pre-existing beliefs (see Nickerson 1998). Relatedly, the belief bias is the tendency to rate the strength of an argument on the basis of whether or not we agree with the conclusion. In other words, if you agree with the conclusion, you'll set low standards for the arguments that argue for that conclusion; if you disagree with a conclusion, you'll set a higher bar for arguments that argue for said conclusion. This is clearly a double standard, but one we don't tend to notice. We will see various cases of these in this course.

I'll give you two examples of how confirmation bias might arise. Although this happened long ago, it still stands out in my memory. One student felt strongly about a particular ethical theory I was covering in my PHIL 103 course: Ethics and Society. This person would get agitated when we would critique the view, and we couldn't have a reasonable class discussion about the topic while this person was in the room. I later found out that the theorist who was highlighted in that theory worked in the discipline of anthropology, the same major that the student in question had declared. But the fact that the theorist who endorses a particular theory is in your field is not a good argument for the truth of the theory. In fact, I can cite various anthropologists who don't side with the theory in question. As a second example, take the countless debates that I've had with vegans about the argument from the Food for Thought section. There is an objection to that example every time I present it. Again, this is not to say that veganism is false or that animals don't have rights, or anything of the sort(!). There are good arguments for vegetarianism and veganism, as you can see if you take my aforementioned PHIL 103 course. But we have to be able to call bad arguments bad. And the argument presented in the Food for Thought is a bad argument.

As an exercise, try to see why the following are instances of confirmation bias:

- Volunteers given praise by a supervisor were more likely to read information praising the supervisor’s ability than information to the contrary (Holton & Pyszczynski 1989).

- Kitchen appliances seem more valuable once you buy them (Brehm 1956).

- Jobs seem more appealing once you’ve accepted the position (Lawler et al. 1975).

- High school students rate colleges as more adequate once they’ve been accepted into them (Lyubomirsky and Ross 1999).

By way of closing this section, let me fill you in on the aspect of confirmation bias which makes it a truly worrisome phenomenon. What's particularly worrisome, at least to me, is that confirmation bias and high-knowledge are intertwined—and not in the way you might think. In their 2006 study, Taber and Lodge gave participants a variety of arguments on controversial issues, such as gun control. They divided the participants into two groups: those with low and those with high knowledge of political issues. The low-knowledge group exhibited a solid confirmation bias: they listed twice as many thoughts supporting their side of the issue than thoughts going the other way. This might be expected. Here's the interesting (and worrisome) finding. How did the participants in the high-knowledge group do? They found so many thoughts supporting their favorite position that they gave none going the other way. The conclusion is inescapable. Being more informed—i.e., being of high intelligence in a given domain—appears to only amplify our confirmation bias (Mercier and Sperber 2017: 214). Troublesome indeed.

Argument Extraction: Book I (327a-336b)

A First-Rate Madness

We need not limit ourselves to passively reading Plato's Republic. Instead, we should feel free to object to the text, interject with more recent findings, and entertain tangeants. In other words, if Plato's says something that has been shown to be false, we should make this explicit. We should also pepper in all the relevant findings that modern science has to offer. After all, we've learned a lot since Plato published Republic circa 375 BCE; it'd be a shame to not consider these more recent ideas and data. Lastly, even if it is not directly discussed by Plato, we should feel free to entertain nearby ideas and arguments. With that said, here are two ideas related to what Plato wrote about in the portion of Book I that we just covered:

- It is hard to define discrete categories of mental health and mental disorders.

- It is not entirely clear that certain non-normal psychologies, e.g., depression, are always a hindrance to good reasoning.

St. Antony of Egypt, known

for fighting off his demons.

First off, when discussing problems with Cephalus' definition of justice, Socrates mentions how perhaps it is not the best idea to return, say, weapons to those who are mentally unstable. This point seems straightforward at first glance, but there is a conceptual problem lurking in the background. So let's begin with a discussion of how difficult it is to define the categories of mental health and mental disorder.

Here's some history as prologue. It is my understanding that conceptions of what "mental stability" is have varied widely throughout history—and this might be an understatement. For example, in the 3rd century CE, it was a common belief among Christians that demons were ever-present; they were always lurking right around the corner, ready to tempt you into sin. In fact, it seems like early Christians would blame almost any base desire as having been caused by the whisperings of a demon, whether it be procrastination, absent-mindedness, overeating, and sexual urges (see Nixey 2018, chapter 1).

Today, however, I assume you might have some misgivings about someone who interprets their sexual desires or their tendency to procrastinate as being the result of the whisperings of a demon. To say the least, I certainly wouldn't want this person babysitting my children. But I might even venture to say that this person who thinks demons are whispering in his/her ear is mentally unstable. This is because we now understand that things like day-dreaming, procrastinating, and sexualized thoughts are not caused by demons but by regular psychological processes, e.g., lack of intrinsic motivation, lack of incentives, regular hormonal responses to potential mates, etc. What does this tell us? Well, it reminds us that what was once considered psychologically normal can come to be considered psychologically abnormal in time.

The reverse is also true: things that are considered psychologically abnormal can come to be accepted as perfectly fine. For example, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders III (DSM-III), what is sort of the Bible with regards to classifications of mental disorders that is published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA), actually still listed homosexuality as a mental disorder. This particular edition of the manual, by the way, was published in 1980. It was actually not until the DSM-IV, published in 1994, that the subject of homosexuality was finally dropped.

Clearly it's not the case that being a homosexual made you mentally unstable prior to 1994 but not afterward. Instead, what has changed is our conception of what mental disorders are. It is mental health itself that is difficult to define. We can take this line of reasoning further. In Predisposed: Liberals, Conservatives, and the Biology of Political Differences, the authors discuss the arbitrariness of the DSM. To understand their argument, however, you must first learn how being diagnosed by the DSM worked.

Until recently, using the DSM worked something like this. There is a list of symptoms associated with some mental disorder. There was also a specified threshold for the number of symptoms that a patient needed to display in order to be diagnosed with the relevant mental disorder. A psychiatric professional would test for those symptoms, and if you had the requisite number of symptoms, then you have the mental disorder. It was an all-or-nothing type thing.

Here's an example. Consider the DSM-IV's diagnostic criteria for autistic disorder. It listed 12 different symptoms which are themselves split into three distinct categories: impairments in social interaction, impairments in communication, and repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behavior. A diagnosis of autism required a professional to identify at least 6 of the 12 symptoms with at least two of them coming from the first category, one from each of the second and third categories, and all appearing before the age of 3. The authors take it from here:

“This all seems more than a bit arbitrary. How can we be sure that the proper cutoff point for Autistic Disorder is six symptoms rather than five? How do we know that the 'two from column A; one from columns B and C' approach is the appropriate one? Are there really 12 symptoms of autism? Maybe we missed one, or maybe two of those listed are really the same thing. Objectively establishing verifiable criteria to divide everyone into they-have-it-or-they-don't categories is so difficult as to be impossible” (Hibbing et al. 2013: 77)

The authors go on to argue that there is no such thing as neurotypical (a typical brain without a neurodevelopmental disorder), and so to make hard demarcation points—as the DSM does—is untenable. There just is no such thing as an average non-autistic brain, qualitatively speaking. It should be noted too that to pretend that there is something like neurotypical brains is harmful. This is especially the case after one considers the contexts under which the DSM is utilized. Institutions like insurance companies, schools, and social service organizations require a diagnosis before agreeing to, say, a reimbursement, allowing the use of certain medications, or providing special tutoring. In the legal domain, things are even more complicated. Any legal decision that requires neatly partitioned psychiatric categories is going to be controversial. Where’s the cutoff for, say, insanity? What’s so magical about age 18? What about people with brain tumors that cause them to break the law? The authors admit that there are no easy answers to these questions, but they make the point that pretending there are neatly organized mental disorder categories appears to be completely unfounded.3

Last but not least, let me say something about the possibility that non-normal psychologies might actually be advantageous. One fascinating example is known as depressive realism. This is the hypothesis that depressed individuals may be better able to make certain judgments when compared to non-depressed individuals (Moore and Fresco 2012). The idea is as follows. Non-depressed individuals, due to their healthy mental disposition, have a tendency to view the world through optimistic lenses. This is perfectly adaptive in an evolutionary sense. It clearly is better for you to think that you are smarter and better looking than you really are if it helps you engage in social situations more effectively; being depressed, having low self-esteem, and lacking motivation are clearly hindrances in many social settings. However, depressed individuals, while they are not always effective in social settings, are at least free from the biases of non-depressed individuals, like the optimism bias just mentioned as well as the "illusion of control" (the tendency for people to overestimate their ability to control events). Being free from these biases, depressed people can actually perform better at certain tasks, such as self-assessing their performance in a difficult task without being given feedback (ibid.).

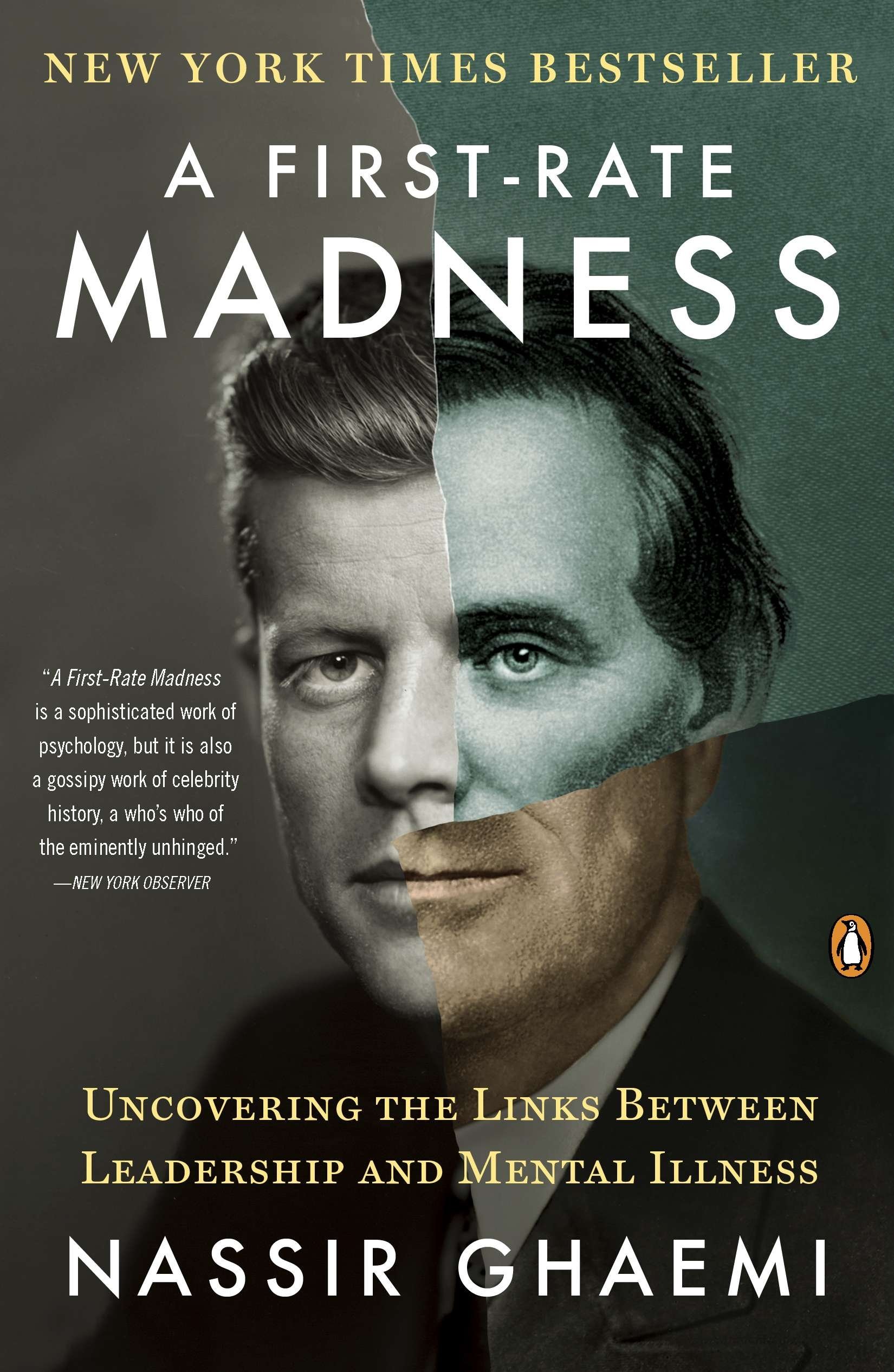

Some theorists have taken this idea further. Ghaemi (2012) argues that individuals with non-normal psychologies, such those suffering from depression and bipolar disorder, actually improve their capacity to deal with adverse events. He makes the case that many of history's most notable political figures, like William Tecumseh Sherman, Abraham Lincoln, Winston Churchill, JFK, and Napoleon Bonaparte, had non-normal psychologies, learned how to deal with adversity because of that, and actually managed to be better leaders because of these skills learned from having to live with non-normal psychologies.

Another interesting theory comes from Dutton (2012). In The Wisdom of Psychopaths, Dutton advances his functional psychopath hypothesis, arguing that (in some contexts) psychopathic traits can be advantageous. Stay tuned.

Welcome to the Do Stuff section. In this section you will find your homework assignments, as well as recommendations for how to prepare for the tests. For today:

- Read from 327a-336b (p. 1-12) of Republic.

- Be sure to review the argument form of modus tollens described in the Argument Extraction video. Also, attempt to write the argument found in 334b-334d in standard form, i.e., numbered form. It's about making mistakes about who your friends really are.

Four important concepts that will be recurring in this course are the notion of logical consistency and the concept of an argument, as well as informal fallacies and cognitive biases.

In the first half of Book I of Republic, Socrates easily dispenses with two faulty definitions of justice: that justice is speaking the truth and giving to each what is owed to them and that justice is benefiting your friends and harming your enemies.

There is a conceptual difficulty in attempting to define the notions of mental disorder and mental health.

It's possible that some non-normal psychological traits might actually be beneficial for reasoning and/or performance in given tasks, as is hypothesized in the theories of depressive realism and the functional psychopath hypothesis.

FYI

Supplementary Material—

-

Reading: Antonis Coumoundouros, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Entry on Plato: The Republic

- Note: This resource might be helpful throughout the semester.

-

Video: Yale Courses, Introduction to Political Philosophy, Lecture 4

-

Video: School of Life, Plato

Related Material—

-

Reading: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Entry on Fallacies

-

Note: Most relevant to the class are Sections 1 & 2, but sections 3 & 4 are very interesting.

-

Text Supplement: Useful List of Fallacies

-

Advanced Material—

-

Reading: Richard Kraut, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Entry on Plato

Footnotes

1. I was informed about this saying by multiple people during my visit to Estonia, a former Soviet satellite. The Russians, it appears, had to have a heavy hand in Estonia to maintain them under Soviet control.

2. Contrary to popular belief, apparently baldness is not all your mother's (gene's) fault. In the very least, smoking and drinking have an effect.

3. For a discussion of the relationship between compromised neural structures and moral responsibility (as well as legal culpability), see What Could've Been.