The Enigma of Reason

Whereas reason is commonly viewed as the use of logic, or at least some system of rules to expand and improve our knowledge and our decisions, we argue that reason is much more opportunistic and eclectic and is not bound to formal norms. The main role of logic in reasoning, we suggest, may well be a rhetorical one: logic helps simplify and schematize intuitive arguments, highlighting and often exaggerating their force. So, why did reason evolve? What does it provide, over and above what is provided by more ordinary forms of inference, that could have been of special value to humans and to humans alone? To answer, we adopt a much broader perspective. Reason, we argue, has two main functions: that of producing reasons for justifying oneself, and that of producing arguments to convince others.

~Dan Sperber & Hugo Mercier

Historical trends and forces

Just as cultural relativism was forged during and shaped by important historical events, such is the case with the remaining theories left in this unit. Vernant (1965) reminds us that the era in which Aristotle was operating was one in which the Greeks were moving towards rationalism and away from myth. He writes that Greeks were no longer satisfied with supernatural explanations for natural phenomena. "[T]he powers that make up the universe and whose interplay must explain its current organization are no longer primeval beings or the traditional gods. Order cannot be the result of sexual unions and sacred childbirth” (Vernant 2006: 219). Intellectuals, as they were moving away from myth, put all their stock in the power of reason. And so Aristotle dared to reduce morality to being realized only in human dispositions and behaviors. The same is true for utilitarianism and Kantianism. Alasdair MacIntyre (1981) reminds us that utilitarianism and Kantianism were a result of what he calls the hubris of the Enlightenment. That is to say that these theories were developed during a time when faith in reason was at a high point. Anthropologist Robin Fox, in fact, thinks academics are still too enamored with reason (see Fox 1989: 233-4). And it was out of this arrogance that came the attempt to ground morality itself in reason. Hubris indeed. Last but not least, moral skeptics are heavily under the influence of a revolution in science that is still taking place: the Darwinian inversion of reason.

Today we are reassessing virtue ethics and Kantianism, jointly. This is because in both theories reason plays a central role...

Virtue ethics

Aristotle, of course, believed that we can use reason to tease out what virtues we ought to strive for. By studying vices, which are either deficits or excesses of virtue, we can surmise the mean (the middle). In other words, we can see that cowardice is a vice, but we can also see that at the other end of the spectrum is rashness, which is also a vice. Neither are desired traits. But through reason we can infer that between cowardice and rashness lies courage, and so reason can help us discover that courage is a virtue.

Aristotle goes further. He believed that we could use our intellectual capacities to train ourselves to be virtuous. Through practice, we can make ourselves disposed to performing the right actions without any internal conflict. But practice, of course, has to be deliberate. And so reason again plays a vital role: reason helps us acquire virtues. This is indeed a lot of faith in reason and its capacity to acquire accurate beliefs. Aristotle is implicitly making the claim that unaided reason can lead us to accurate beliefs about virtues and about how to best train ourselves to embody those virtues. Let's call this the intellectual function hypothesis.

Another empirical claim that Aristotle made was the following. Aristotle believed that once we’ve developed the right virtues, the right actions will flow out of us when we are put in certain situations. This can be tested for, in theory. Find a virtuous person, put them in a situation that challenges their integrity, and see how they perform. On balance, an virtuous person should do the right thing more often than a non-virtuous person. Let's call this the good-character-good-behavior hypothesis.

One last point before moving on... There are other traditions of virtue ethics. We covered, for example, the ethics of care, a Buddhist virtue ethics, and Nietzsche's views as virtue ethics. But these all pull their theoretical power from Aristotle's basic reasoning. So, for our purposes, we will treat them as a group. This means that if Aristotle falls, they all fall.

Kantianism

Recall that Kant believed that human reason (i.e., the capacity to make inferences) is the source of moral law. In fact, Kant believed that reason is the basis not only of our moral code, but also for our belief in God, free will, and even the immortality of the soul. He argued for this through his transcendental deduction (see Rohl 2020). Although duty, as opposed to virtue, is central to Kant's moral theory, Kant still believes that human reason is a very powerful faculty. As such, we will also count him as positing the the intellectual function hypothesis.1

The intellectual function hypothesis

A crow using a tool.

What is the evolutionary function of reason? In other words, what did reason evolve to do? The question might seem strange at first. We are not used to thinking about our ability to reason, or to make inferences, as a biological trait that evolved. After a little reflection, however, we realize that indeed the capacity to reason is an evolved trait that we (humans) have but not, say, a caterpillar. We now know that various animals perform what appear to be intelligent behaviors through instinct. But we think, we learn, and we make inferences to a degree not matched in the animal world. Sure, some crows and non-human primates display an excellent ability with tools, but no crow or non-human primate could learn how to write a computer program or workout a calculus problem, no matter how long we trained them. So this capacity must've evolved at some point, for some reason.

Aristotle and Kant, although they never explicitly said this (since they were around before the theory of Darwinian evolution came about), would claim that reason evolved so that we could form better, more accurate beliefs. Reason is for understanding the world, so that we may better respond to it, and for understanding our lives, so that we may better live them. This is what we are calling the intellectual function hypothesis. And so far it has looked pretty good for them. Even Darwin himself seems to have thought this was the likely reason for why reason evolved.

“Darwin was content to explain the acquisition of our species’ cognitive abilities as a result of the pressure of natural selection on our precursors over long periods of time. And most scientists today, it would seem, concur with him... Wallace [co-inventor of the notion of evolution by natural selection], however, simply could not see how natural selection could have bridged the gap between the human cognitive state and that of all other life forms. What he did see was the breadth and depth of the discontinuity between symbolic and nonsymbolic cognitive states... As far as we know, modern human anatomy was in place well before Homo sapiens began behaving in the ways that are familiar today” (Tattersall 2008: 101-2; emphasis added).

Nonetheless, only in the last decade or so, a new type of theory about the origins of reasoning has emerged. In fact, many cognitive scientists are moving towards the view that our capacity to reason has a social-communicative origin. This means that reason did not specifically evolve for truth-tracking (the intellectual function). Instead, reason appears to have originated to help us coordinate the social problems that arise from living collaboratively, a way of living we've seen is a part of our evolutionary history.

For example, Tomasello (2018) argues that we developed our capacity to reason in order to better communicate reasons for plans of action for the group. Because collaborating effectively was a matter of life or death for members of tribes, tribes with members who were better able to come up with plans of actions by giving reasons for their plans were more likely to outcompete tribes who didn't have such members. Moreover, the entire tribe was more likely to survive and pass on their genes. Slowly, tribes with members that were able to give reasons for their actions dominated, and so these genes became dominant in the gene pool.

Another theory, this time by Mercier and Sperber (2017), makes the case that we developed reason in order to win arguments. This is because, for most of our evolutionary history, to be without a tribe was certain death. So, if you did something against some member of your tribe, especially during trying times, your only hope was explaining yourself (so that you're hopefully forgiven). Those persons with the capacity to give reasons for their actions and views were more likely to survive and hence pass on their genes. Here is Hugo Mercier explaining his view:

Note that these theories aren't entirely incompatible. Moreover, these theories explain why our reasoning capacity seems to have a built-in confirmation bias. Think about it. You are always naturally disposed to bias your view over that of someone else. Why would this be? One good reason for this might be that reason evolved to defend your view, to explain your actions, to argue for your plan. This view is growing to be so convincing that, at the end of his A Natural History of Human Thinking, Tomasello makes the case that some social-communicative theory must be true.

What does this mean for us? It means two things. First off, if reason has a built-in confirmation bias, then there is a risk that reason does not help us arrive at virtues that allow for human flourishing (eudaimonia) or objective moral values, but instead merely defends our pre-existing biases about how we think we should live. I mean, isn't it convenient that when Aristotle thought about the way one should live, the set of virtues he came up with were that of an aristocrat right around the time he was tutoring Alexander the Great? That smells like confirmation bias. Just like in the Necker cube pictured, you see what you want to see.2

Second, if a social-communicative type of theory is true, then that means that an intellectual function theory is not true. In other words, reason doesn't do what Aristotle and Kant thought that it did. A swing and a miss...

Food for Thought

Good character, good behavior?

Batson comes back

Now we must address the good-character-good-behavior hypothesis. We begin with a return to the work of Daniel Batson. Batson (2016: 42-3) reviews the data from the Character Education Inquiry, a massive, longitudinal study into schoolchildren’s honesty and generosity. The results are not good for Aristotle… “Rather than a general trait (i.e., virtue) of honesty, many children seemed to have more nuanced standards tuned to specific circumstances. Instead of ‘Thou shalt not cheat,’ the behavior of many was more consistent with, ‘Thou shalt not cheat unless you need to in order to succeed and can be certain you won’t get caught.’”. So at least in children, good character did not necessarily result in good behavior. They seemed to primarily follow very self-serving rules, once again showing how dominant confirmation bias is in our cognition. But it gets worse...

Doris' empirical assault

The findings of social psychology that started trickling out in the 20th century are fascinating, and much ink has been spilled about what they tell us about human nature. John Doris saw something very particular in this data: the possibility of refuting virtue ethics. In Lack of Character, John Doris (2010) goes on an all-out empirical assault on virtue ethics.

Let's begin with Milgram's famous experiments on obedience. I'm sure many of you have heard of Milgram's experiments, so I will not recount the entire experiment here (but you can see the video below). The finding of interest for us is that a majority of subjects, if coaxed by a researcher (just a man in a lab coat), gave the maximum voltage shock to the learner despite the learners’ protestations, complaints of heart issues, screams, and eventual silence. All in all, 65% of subjects administered all the shocks, despite the nervous laughter exhibited by many of them (who presumably knew they were doing something wrong). These findings were replicated many times by Milgram (and partial replications were done by others, e.g., Burger 2009). One replication, even involved using real shocks on puppies (Sheridan and King 1972), where many of the subjects were openly crying.

Another experiment of relevance was performed by Philip Zimbardo, who coincidentally went to high school with Stanley Milgram. This has come to be known as the Stanford Prison Experiment. Since many of you also know the background of this experiment, I won't recount it. The finding of interest, however, is that young male Stanford students randomly selected to be guards took on the role of a prison guard and began to behave in increasingly sadistic ways towards the prisoners. This escalated until the experiment had to be terminated. Below you can see the preview for a film depicting a dramatization of the experiment.

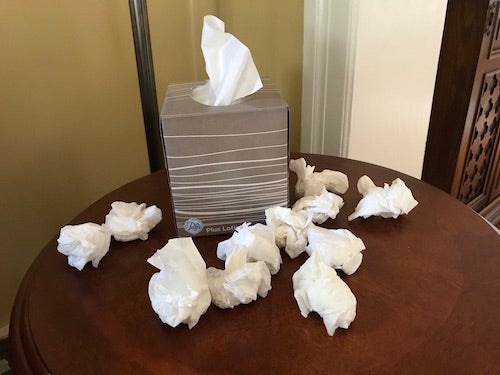

Dirty tissues.

To these very famous experiments we add more mundane but equally perplexing experiments. For example, there's the finding that we make harsher value judgments when we breathe in foul air (Schnall et al. 2008) or have recently had bitter (as opposed to sweet) drinks (Eskine, Kacinic, and Prinz 2011). It's also the case that good smells appear to promote prosocial behavior (Liljenquist, Zhong, and Galinsky, 2010). Apparently, washing your hands before filling out questionnaires causes you to be more moralistic (Zhong, Strejcek, and Sivanathan 2010). In fact, merely answering a questionnaire near a hand-sanitizer dispenser makes you temporarily more conservative (Helzer and Pizarro 2011). A person’s tendency to act dishonestly can be enhanced by their wearing sunglasses or being placed in a dimly lit room (Zhong et al. 2010). Lastly, moral opinions can be made more harsh if there is a dirty tissue nearby (Schnall, Benton, et al. 2008).

This is only the tip of the iceberg with regards to the so-called situationist challenge. Doris fills his book with such experiments. But what do we learn from this? Doris puts it this way:

“Social psychologists have repeatedly found that the difference between good conduct and bad appears to reside in the situation more than in the person” (Doris and Stich et al. 2006; emphasis added).

Fellow critic of virtue ethics, Gilbert Harman, goes further and claims we must now be skeptical of the existence of robust character traits in humans. He puts his tentative conclusion this way:

“I do not think that social psychology demonstrates there are no character traits [or virtues]... But I do think that results in social psychology undermine one’s confidence that it is obvious there are such traits” (Harman 2008: 12; interpolation is mine).

In short, the social situation you are in appears to dominate your behavior, moral or otherwise—this is a basic tenet of situationism. If you want to guarantee good behavior, you are apparently better off attempting to control your social environment than you are developing some set of virtues. Big miss for Aristotle.

Taking stock...

/5727759849_685be7a535_o-56a793f05f9b58b7d0ebdb27.jpg)

In this lesson we address the intellectual function hypothesis, the view that reason is for acquiring more accurate beliefs about ourselves and the world—a view that both Aristotle and Kant seem to accept; we also consider the good-character-good-behavior hypothesis, the view that if one develops robust virtues then one will be inclined to behave in the right ways when situations that call for virtue arise—a hypothesis advanced by Aristotle.

With regards to the intellectual function hypothesis, we can say that theories regarding the origins of our capacity to reason are veering towards a socio-communicative origin—not the intellectualist hypothesis. Moreover, socio-communicative theories about the origins of reason explain why we seem to have a built-in confirmation bias—which appears to be a feature of our capacity to reason rather than a bug.

With regards to the good-character-good-behavior hypothesis, the situationist challenge that is embodied by experiments like the Stanford Prison Experiment and Milgram's Obedience to Authority studies seems to radically undermine our confidence that character traits (like virtues) are more predictive of behavior than the social situation one finds themselves in.

Although the good-character-good-behavior hypothesis was labeled as not true, even if we update it to an open question, the situation is not good for Aristotle, at least with regards to the social science. Aristotle is dismissed from further analysis, while Kant lives to fight another day—against the utilitarians.

FYI

Suggested Reading: John Doris and Stephen Stich, et al., Virtue Ethics and Skepticism About Character

TL;DR: Crash Course, Social Influence

Supplemental Material—

-

Video: Philip Zimbardo, Power of the Situation

Video: VSauce, The Future of Reasoning

-

Audio: Philophy Bites Podcast, Dan Sperber on The Enigma of Reason

- Note: Both audio and links to Sperber's work are found in this link.

-

Video: The You Are Not So Smart Podcast, Why do humans reason? Arguments for an argumentative theory

- Note: Both audio and a transcript to the podcast are found in this link (near the bottom).

Advanced Material—

-

Reading: Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber, Why do humans reason? Arguments for an argumentative theory

-

Reading: John Doris, Persons, Situations, and Virtue Ethics

Footnotes

1. Kant in fact makes other empirical claims. For example, as part of his transcendental deduction, he argued that time was not objectively real—a view that some contemporary physicists are backing (see Rovelli 2018). Kant also made accurate astronomical predictions, such as the view that other planets must exist outside of our solar system and the nebular hypothesis (the hypothesis that the Solar System is formed from gas and dust orbiting the Sun). He also made ghastly "anthropological" claims (as was discussed in The Tree of Knowledge...) which are not worthy of further mention.

2. The work of Thomas Gilovich (1991) is an excellent primer on motivated reasoning and confirmation bias. Basically, Gilovich finds that if someone has a pre-existing bias to believe in something, they look at the available evidence and ask themselves, “Can I still believe the thing that I wanted to believe?” and they look for ways to make that possible. If they wanted to disbelieve something, they look at the available evidence and ask, “Do I have to believe the thing I don’t want to believe?” and they look for ways to avoid believing what they don’t want to believe.