The Jungle

The fear of you and the dread of you shall be upon every beast of the earth and upon every bird of the heavens, upon everything that creeps on the ground and all the fish of the sea. Into your hand they are delivered. Every moving thing that lives shall be food for you. And as I gave you the green plants, I give you everything.

~Genesis 9: 2-3

They had done nothing to deserve it; and it was adding insult to injury, as the thing was done here, swinging them up in this cold-blooded, impersonal way, without a pretense of apology, without the homage of a tear. Now and then a visitor wept, to be sure; but this slaughtering machine ran on, visitors or no visitors. It was like some horrible crime committed in a dungeon, all unseen and unheeded, buried out of sight and of memory.

~Upton Sinclair

The traditional perspective

At least some parents—parents that I personally know— have had to deal with their child's meltdown when the latter finds out that meat comes from animals. I'm not sure how frequent this scenario is, although more than a handful of students have reported to me that they themselves had such a breakdown. Typically, children resume their consumption of meat after an appropriate period of adjustment. We can gather as much since less than 10% of Americans are either vegan or vegetarian. Nonetheless, we can pause here and reflect on that meltdown, consider the chaotic mix of emotions and attempted justifications that I'm sure were expressed during that evening. Today's topic is the human use of non-human animals.

There are many ways in which humans make use of animals. In this lesson, however, we will focus on two: animal experimentation and animal consumption. Let's begin, though, by distinguishing between two very different approaches to animal ethics. There are those who believe that animals don't have moral rights at all; let's call them rights deniers. On the other hand, there are those who claim that animals are a part of the moral community; let's call them rights affirmers. Throughout history, going back into antiquity, the norm has been to be a rights denier (as can be seen in the first epigraph above). It is only recently that animal rights affirmers have begun to become more numerous. An early example of this can be found in the work of Upton Sinclair, who published The Jungle in serial form throughout 1905 (see the second epigraph above).1

René Descartes

(1596-1650).

You can find rights deniers at the very beginning of the Western Tradition. For example, Aristotle in his Politics (Book I, Part VIII) wrote that plants are created for the sake of animals and that animals are for the sake of humans, both for food as well as for clothing. This perspective on animals was remarkably persistent. More than a thousand years later, in his Summa Theologiae (Part 2, Question 64, Article 1) Saint Thomas Aquinas wrote that animals were intended purely for human use. He argued, hence, that it is not wrong for humans to make use of them either by killing them for food or in any other way whatsoever. And then, a few centuries after Aquinas, René Descartes argued that animals were just automata (machines designed for some function), and so they could not feel pain (see Harrison 1992 for analysis).

Moreover, it appears that it was not just the philosophers that were rights deniers. It appears that religious institutions were also denying non-human animals entry into the moral community. Frey (2010: 168-9) reports that the traditional justification for the human use of non-human animals was rooted in the Judaic/Christian ethic itself. On this topic, Harari (2017) reminds us that religious institutions as we know them today do not at all resemble these same religious organizations at their inception.

“How did farmers justify their behaviour? Whereas hunter-gatherers were seldom aware of the damage they inflicted on the ecosystem, farmers knew perfectly well what they were doing. They knew they were exploiting domesticated animals and subjecting them to human desires and whims. They justified their actions in the name of the new theist religions, which mushroomed and spread in the wake of the agricultural revolution. Theist religions maintained that the universe is ruled by a group of great gods—or perhaps by a single, capital ‘G’ god (‘Theos’ in Greek). We don’t normally associate this idea with agriculture, but at least in their beginnings theist religions were an agricultural enterprise. The theology, mythology and liturgy of religions, such as Judaism, Hinduism and Christianity, revolved at first around the relationship between humans, domesticated plants and farm animals. Biblical Judaism, for instance, catered to peasants and shepherds. Most of its commandments dealt with farming and village life, and its major holidays were harvest festivals. People today imagine the ancient temple in Jerusalem as a kind of big synagogue were priests clad in snow white robes welcomed devout pilgrims, melodious choirs sang psalms and incense perfumed the air. In reality, it looked much more like a cross between a slaughterhouse and a barbecue joint [as opposed to a modern synagogue]. The pilgrims did not come empty-handed. They brought with them a never-ending stream of sheep, goats, chickens and other animals, which were sacrificed at the god’s altar and then cooked and eaten” (Harari 2017: 90-1; see also Numbers 28, Deuteronomy 12, and I Samuel 2).

The 20th century, though, saw a proliferation of ethicists advocating for animal rights (Rossi & Garner 2014: 480). This is not to say, however, that all ethicists agree that animals can't be used at all. The issue is, in fact, complicated. No other issue shows how complicated it really is, I think, like the topic of animal experimentation.

Human benefit

Stephen Hawking, likely

the most famous

patient with ALS.

It is unquestionable that humans gain from experimentation on animals. For example, through genetic engineering, scientists can insert certain genes into a non-human animal's DNA, thereby creating a "new" animal that can contract the same illnesses that humans can contract. Once this is done, the goal is to study the progress and pathology of the illnesses in these "new" creatures and learn something about how to treat these illnesses in humans. So, by inserting a human gene into, say, a mouse, scientists can get a deeper understanding of dreadful diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Huntington's disease, and Tay-Sachs disease. If you're lucky enough to not know what these diseases are like, you at least likely do know about Stephen Hawking, perhaps the

most famous patient with ALS. All in all, it is undeniable that these animal models are invaluable to research into disease, the mind, and much more (Kandel 2018).

It doesn't end there. There is also the interesting topic of xenografts, or cross-species transplantations. Scientists could genetically engineer a type of, say, baboon or pig, with human organs bred into them for the express purpose of transplanting these organs to human patients who need them to survive (Frey 2010: 164-65).

"The very similarities of primates to ourselves genetically, physiologically, pathologically, metabolically, neurologically, and so on make them the model of choice for research into numerous human conditions. With stem cells from rhesus monkeys and marmosets isolated in 1994, we took a step towards the possibility, through inserting into the monkey the gene correlated with a certain disorder, of genetically engineering monkeys that had amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, cystic fibrosis, and so on. It is precisely because of their similarities to ourselves in the ways indicated that the ability to produce primates that have human illnesses stirs the medical community" (Frey 2010: 165).

Of course, there is a purely non-moral drawback to using animals for research in pathology: they're not human. In other words, there's still not quite identical to humans, so any lessons learned from their pathologies won't always directly transfer to humans. But this puts us in a predicament. If experimentation on animals can yield some positive results, albeit imperfectly transferrable to humans, wouldn't experimenting on humans yield even more positive results. In other words, if positive results is what we're after, then why draw the line at animals? Why not experiment on humans too? This, at least according to Frey (2010), is the central problem to be addressed in the debate on animal experimentation: the appeal to human benefit cannot stand alone as a justification of animal experimentation, since it would also justify human experimentation.

A roborat2.

I should say two things at this point. First, if the proposal to experiment on humans sounds ridiculous to you and it makes no sense to even entertain the idea, I sympathize with you. That was my exact reaction when first reading Frey. But(!), he's right in that if one is thinking from a purely consequentialist perspective, obviously experimenting on humans could potentially lead to some medical breakthroughs that would enhance our life expectancy and quality of life. In other words, if one is a. not a rights denier (and hence a rights affirmer), but b. wants to use consequentialist moral reasoning to justify experimenting on animals, then c. one needs a good justification for drawing a solid line between non-human animals and humans, since d. experimenting on humans really would be even more beneficial for science—or so it seems. Second, drawing this solid line between non-human animals and humans is harder than you think.

Suppose, for example, that one wants to draw a line between humans and animals as determined by certain set of cognitive abilities. For instance, Kant famously awards moral status only to Rational Beings. Here's the problem with this tactic: there is a number of humans who fall outside of this protected class. In other words, there are some humans with cognitive deficiencies who cannot truly be said to be Rational Beings. So, if we were to use Kant's criterion for personhood, it is not clear that we could rule out experimentation on certain humans.

Say, instead, that we can draw the line between humans and animals by making the case that humans have a greater potential for richer and higher quality life experiences than the life experiences of, say, a mouse (ibid., 178-79). Again, the response here is that humans vary greatly in their potential for meaningful, rich life experiences. If the potential for rich life experiences of some humans were to dip below the level of, say, a mouse, then wouldn't this make it permissible to experiment on them? The demarcation problem is a terrible problem indeed (ibid., 182-84).

“In short, the search for some characteristic or set of characteristics, including cognitive ones, by which to separate us from animals runs headlong into the problem of marginal humans (or, in my less harsh expression, unfortunate humans). Do we use humans who fall outside the protected class, side effects apart, to achieve the benefits that animal research confers? Or do we protect these humans on some other ground, a ground that includes all humans, whatever their quality and condition of life, but no animals, whatever their quality and condition of life, a ground, moreover, that is reasonable for us to suppose can anchor a moral difference in how these different creatures are to be treated? But then what on earth is this other ground?” (Frey 2010: 172-73).

Eating animals

Regan (1983/1986)

Animal agriculture and climate change

Perhaps we can obviate the need for wandering into the thorny territory of defending some theory of moral rights by instead discussing the negative consequences of animal agriculture. For example, we know that raising livestock is fueling global climate change. In fact, by some estimates, animal agriculture accounts for 9% of total carbon dioxide emissions, 40% of total methane emissions, and 65% of total nitrous oxide emissions. So, if global climate change continues unabated, the ongoing droughts in parts of the world will make raising livestock unsustainable. Using this information, one can make a Kantian-type argument. Essentially, our current practices are unsustainable. If everyone consumed and emitted greenhouse gases the way the West is currently consuming and emitting, then soon the practice will have to be discontinued. In other words, this seems to violate the categorical imperative, and a Rational Being would not engage in this type of behavior.3

Relatedly, by opening up the discussion to include the effect of animal agriculture on the environment, we find ourselves with a new problem. A new line has to be drawn—one between our consumption practices that are acceptable and those that are not. According to the EPA, about 75% of our greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions come from our transportation sector, our production of electricity, and our industrial sector. A plurality of it is actually from our transportation sector. As such, it appears that our consumerist lifestyle contributes to GHG emissions, since the products we buy have to be manufactured (using natural resources and electricity) and then delivered to us or our local retail establishment (transportation). Thus, if the rationale for not eating meat is the negative environmental factor of animal agriculture, then it would be inconsistent to not also put an end to unnecessary consumerist lifestyle choices.4

Marion Hourdequin.

So now we have to draw a line, and this line is as hard to draw as is the line between non-human animals and humans on the question of experimentation. So, do we have to do everything in our power as individuals to not contribute to GHG emissions? Or is there an acceptable amount of emissions that we can contribute? Which behaviors that emit GHG are acceptable? Baylor Johnson (2003), for his part, argues that under current circumstances, individuals do not have obligations to reduce their personal contributions to GHG emissions, only to fight for policy that mandates collective action. This is because only the coercive apparatus of the state is powerful enough to actually bring about effective change. Individual consumers alone simply do not have the desired effect; becoming vegan is, on Johnson's view, completely ineffectual.

On the other hand, Hourdequin argues that “we have moral obligations to work toward collective agreements that will slow global climate change and mitigate its impacts, [but] it is also true that individuals have obligations to reduce their personal contributions to the problem” (2010:444). In other words, you have to both make individual changes as well as push for the state to use its coercive powers to compel the population to change. How does she argue for this? Interestingly, at least to me, she argues from the perspective of Confucian philosophy:

“Confucian philosophy does not understand the individual as an isolated, rational actor. Instead, the Confucian self is defined relationally. Persons are constituted by and through their relations with others… The Confucian model is, further, one in which individuals look to one another as examples, learning from one another what constitutes virtuous behaviour. Confucius believes that moral models have magnetic power, and virtuous individuals can effect moral reform through their actions by inspiring others to change themselves” (Hourdequin 2010: 452-3).

Clearly, only a multinational effort to curb climate change will work. So, we need states, along with their coercive powers, to launch campaigns for green energy. However, Hourdequin makes a good point. Clearly, we need to start at the level of the community. By making more virtuous choices, we can influence our friends and neighbors. It does seem like we should start at home. But how far do we have to go?

Sidebar

Animal agriculture and the effect on workers

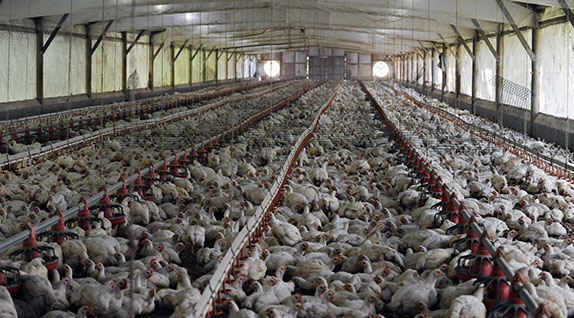

Although we cannot really get into this issue here, it appears that animal agriculture has negative effects on its workers. The little that I know about this is pretty horrifying. For example, denied breaks, US poultry workers wear diapers on the job. It's also the case that, according to some, factory farming often has very questionable working conditions, which some argue lead to higher incidence of crime, although this is disputed. Here's what we can say, though. Regardless of the precise details, it's not terribly controversial to say that farm workers are generally exploited (Linder 1992, ch 1). So, even if you’re a vegan, and hence are not directly exploiting animals for sustenance, unless you grow your own foods, you are still using the exploited labor of farm workers. It appears that it's almost impossible to eat without exploitation being injected in at some point. Surprisingly, or perhaps unsurprisingly, even fine dining is suspect. In Kitchen Confidential, Anthony Bourdain (2000: 55-63) reminds his readers that an overwhelming majority of line cooks at fine dining restaurants are non-European immigrants, whether you’re eating French, Italian or Japanese cuisine—immigrants that work under the table and don't typically get very many benefits. This begins to suggest that perhaps questions regarding the ethics of animal consumption extend all the way "up the food chain" to fine dining restaurants and even grocery stores. Is it morally permissible to purchase products at stores that make any kind of profit from animal agriculture? What about restaurants that serve animal products? Aren't you still contributing to their profit even when you take the vegan option? There's also the question of whether or not it is ethical to dine at any restaurants who have unfair practices with regards to their staff. After all, if you're taking great pains to make sure you don't participate in any non-human animal suffering, doesn't it seem like you should do at least as much for your fellow humans?

Go big or go home...

Why are things looking so dire in the animal agriculture sector? Part of it, unsurprisingly, is money...

“From an economic standpoint, [industrial farm animal production] is characterized by farms that are corporate-owned and/or corporate-controlled, instead of farms that are both owned and managed by individuals or families. In a process known as ‘vertical integration,’ distinct phases of the agricultural supply chain, such as crop growing, feed formulation, animal breeding, raising animals, slaughtering animals, and food processing and distribution, are increasingly controlled by large corporate integrators. In addition to vertical integration, there has been significant economic consolidation within the agricultural sector, meaning that fewer companies control ever more of the market share. Across all of agriculture, the largest 10% of U.S. farms now account for more than two-thirds of the total value of production... Four companies control 80% of the meatpacking industry. Perhaps most significantly, while large corporate integrators own only a small percentage of farms, many farmers are now contract growers, meaning that while they may own their land and buildings, they sign a contract with a large integrator (e.g., Tyson or Smithfield) to raise animals that are owned by the integrator. The integrator controls all aspects of how the animals are bred and raised, and sets the price that the grower will receive. Many contract growers report no open-market alternative to their contract. In addition, increases in scale and mechanization have resulted in significantly fewer farmworkers as compared to pre-industrial agriculture. In 1870, approximately 50% of the U.S. population lived and worked on farms; today, that number is less than 2%. Farm laborers are increasingly unskilled, low-wage earners, and many live below the poverty line” (Rossi & Garner 2014: 484).

Including animals as part of the moral community is a relatively recent development. Both divine command theorists, like Thomas Aquinas, and other thinkers, like Aristotle and Descartes, tended to believe that animals are purely for use by humans.

On the issue of animal experimentation, the central problem (per Frey 2010) is to find a justified way to demarcate why it is permissible to experiment on animals but not on humans—a distinction that appears to be difficult to make.

The topic of animal agriculture is just as problematic. Some thinkers believe that no type of animal consumption is permissible. For example, Regan awards animals rights based on some cognitive capacity that they have, i.e., being the subject-of-a-life. This can be construed as a neo-Kantian perspective. But his arguments are not without detractors. Warren responds to Regan with a version of Utilitarianism.

Also discussed is the effect of animal agriculture on the climate, a topic that took us into a conversation about our duties towards the environment. Johnson argues that we need not concern ourselves with individual actions to curb climate change, instead only fighting for a policy of collective action, via a type of social contract theory. Hourdequin responds to Johnson with a Confucian-inspired virtue ethics, arguing that both individual and collective actions should be taken to reduce our GHG emissions.

FYI

Suggested Reading: Tom Regan, The Case for Animal Rights

Supplementary Material—

Video: CrashCourse, Personhood

Video: Great Ideas of Science and Philosophy, Interview with Peter Singer

Video: Practical Ethics Channel, Peter Singer tackles the best objections to vegetarianism

Advanced Material—

Reading: Jan Narveson, The Case Against Animal Rights

Reading: Marion Hourdequin, Climate, Collective Action and Individual Ethical Obligations

Related Material—

Video: Big Think, How Healthy Is Vegetarianism...Really?

Other Material—

Material on Animal Treatment

Reading: Nita Rao, In the Belly of the Beast

Material on Animal Agriculture and Climate Change

Reading: Maurice E. Pitesky, Kimberly R. Stackhouse, and Frank M. Mitloehner, Clearing the Air: Livestock’s Contribution to Climate Change

Material on the Dietary Impact of Climate Change

Reading: Damian Carrington, Eat insects and fake meat to cut impact of livestock on the planet – study

Material on the Exploitation of Agriculture Workers

Reading: Oxfam Report on denial of bathroom breaks in poultry industry

Reading: Thomas Dietz and Amy J. Fitzgerald, Slaughterhouses and Increased Crime Rates

Related Reading: Georgeanne M. Artz, Peter F. Orazem, and Daniel M. Otto, Measuring the Impact of Meat Packing and Processing Facilities in the Nonmetropolitan Midwest: A Difference-in-Differences Approach

Note: This is a response to Dietz and Fitzgerald.

Reading: Marc Linder, The Pillars of an Inexhaustible Supply of Cheap Labor

Footnotes

1. Interestingly enough, Sinclair's primary goal in The Jungle was to advance the cause of socialism by exposing the hardship of the workers in the meat industry. However, many of his readers focused on the industry's several health violations and unsanitary practices instead.

2. I discuss roborats in Laplace's Demon, from my PHIL 101 course.

3. There may be some other food-related perils down the road. The price of meat will soar by 2050, due to population growth. Moreover, even vegetarians will be affected, since rising temperatures will also hurt production of staple crops like maize and wheat.

4. I might add that it is also the case that consumerist/materialistic values are associated with a decrease in prosocial behaviors, an increase in apathy towards environmental issues, and an increase in feelings of depression and lack of fulfilment (Kasser 2002; see also this video based on Kasser’s work).