The Master

“Let no one ignorant of geometry

enter here.”

~Inscription written

over the door of Plato's Academy

Math on Plato

Our introduction to Plato was through his philosophy of mathematics (in the previous lesson). I admit that this is not the conventional way of discussing Plato in philosophy courses. However, mathematics had a profound effect on Plato. He was so taken by the subject that he believed that all knowledge could be like mathematical knowledge. In other words, math literally shaped how Plato understood the world. For Plato, mathematics is a portal into the transcendental, reality as it really is.

I’m not alone in this assessment. Mathematician and historian of mathematics Morris Kline sees that mathematics is central to Plato’s entire conception of knowledge, and he points out that Plato may have even been part of the quasi-religious sect of mathematicians headed by the intellectual descendants of Pythagoras (see Kline 1967: 62-63). There is definitely something to this idea. Notice, for example, the cryptic language that Plato uses when discussing the subject matter—that is, mathematical objects—of mathematicians:

"These very things that they [the mathematicians] model and draw, which also have their own shadows and images in water, they are now using as images in their turn, in an attempt to see those things themselves that one could not see in any other way than by the power of thinking"" (Republic, 510e-511a; emphasis added).

Agreeing that mathematics had a profound impact on Plato, Stewart Shapiro writes on how mathematics influenced Plato's views on knowledge:

“Plato’s fascination with mathematics may also be responsible for his distaste with the hypothetical and fallible Socratic methodology. Mathematics proceeds (or ought to proceed) via proof, not mere trial and error. As Plato matures, Socratic method is gradually supplanted. In the Meno Plato uses geometric knowledge, and geometric demonstration, as the paradigm for all knowledge, including moral knowledge and metaphysics... Plato finds things clear and straightforward when it comes to mathematics and mathematical knowledge, and he tries to extend the findings there to all of knowledge” (Shapiro 2001: 62-63).

Plato’s views on math, in other words, are a good introduction to his philosophical system. As such, let’s recap Plato’s views about mathematical objects before diving into his other views.

Plato on Math

Recall that if one searches for a truthmaker for "2+2=4", then one has a few options. One could side with physicalism, arguing that mathematical objects are just piles of physical stuff. But, unfortunately for the physicalist, physical objects can't account for mathematical concepts like CIRCULARITY and INFINITY, since there are neither perfect circles nor an infinite amount of stuff in the universe. You can also be a conceptualist, arguing that the truthmaker to "2+2=4" is a thought, presumably dependent on the firing of certain neural networks in my brain. But if we all build our mathematical ideas independently and subjectively in our brains, then conceivably this might make mathematical errors impossible. One might say, in other words, that the way they've mentally constructed the number FOUR is as a prime. You can also be a nominalist/fictionliast about mathematical objects, claiming that they are just convenient fictions. But this leaves you having to say that there is no truthmaker for "2+2=4", and that kinda sucks. And so, Plato's idea suddenly becomes appealing. He argued that mathematical objects are abstract objects. That is, mathematical objects are non-physical, unchanging, eternal objects that exist independent of human minds. They exist in another realm, and we typically refer to this other plane of existence where these objects exist as Platonic Heaven (in honor of Plato). It is these objects in Platonic Heaven that serve as truthmakers for "2+2=4".

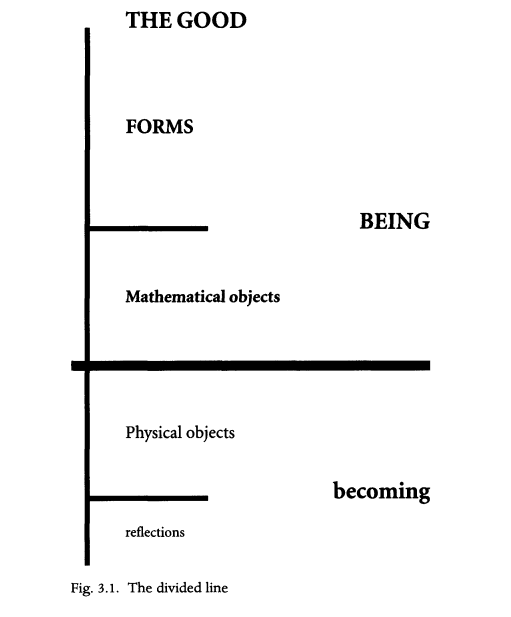

As a metaphor for how he conceived of the world and the objects within, Plato gave us The Divided Line. What Plato has laid out for us is his hiearchy for the reality of objects. In other words, Plato is organizing types of objects from less fundamental to more fundamental. At the bottom are mere copies of things: reflections in the mirror, paintings, and the like. These are only copies of the real thing; for example, your reflection is a mere copy of the real you. The next level up is the realm of physical objects. This is where you and I live, along with all the physical things that we interact with on a day-to-day basis. We might think that this is the ultimate level of reality, but Plato disagrees. Upon reflection, we might come to think that Plato might have a point. After all, the reality that we see with our senses can't be the ultimate reality. We know that physicists tells us about a world of atoms and smaller subatomic particles that we can't see with the naked eye.

Figure 3.1

from Shapiro (2000).

As you can see in the diagram, the next level up consists of mathematical objects. This means that all mathematical objects (like numbers), as well as mathematical relations (like equality) and functions (like adding 1, squaring, and all the more complicated functions) exist in this realm, independent of all human thought. In other words, numbers are real and they are more fundamental than the reality we inhabit. This shouldn't sound too strange if you believe that mathematics has the power to help us understand our world: mathematics has this power because it is upon mathematics that our world is ordered. This is why mathematics is always involved in the sciences and in any other enterprise that involves knowing our world in a deeper way.

Above mathematical objects are The Forms on which our reality is based. These are the actual properties of the universe upon which everything we see is based, according to Plato. To see this realm is to have a "god's-eye-view". In other words, it is to understand reality as it really is. Try to imagine combining all the knowledge of all the disciplines and then extending that knowledge until it is complete, where everything that can be known is known. That is what it is to know The Forms. And of course, The Forms are ordered too, just like everything below it. At the top of the hierarchy is The Good.

And so Plato believed that this realm of The Forms could be understood via the realm of mathematical objects. In other words, to come to know The Forms, one must first know mathematics. Put counter-factually, if you don't go through mathematics, then you will not understand reality as it really is. All of our knowledge, then, will ultimately be based on mathematics; mathematics is the medium through which we can understand the basis of all reality (The Forms). I might add here that this is not at all a far-fetched idea. In his introduction, Turchin (2018) reminds us that academic disciplines mature as they are formalized, i.e., as mathematical modeling is incorporated into the discipline. Plato seems to have intuited that mathematics is fundamental.

Sidebar: Contemporary views

Was Plato right? Is there a primacy to mathematics such that it is more fundamental than our physical reality? What we can say with certainty is that many of the thinkers we've covered so far seemed to have thought so. They readily relied on mathematics as the avenue through which to understand the world. This is so much so the case that, in his intellectual history, John Randall made the following point:

“Science was born of faith in the mathematical interpretation of Nature, held long before it had been empirically verified” (Randall 1976).

This is what I've been repeating over and over again in this course: we're jaded. We know science is the best method for answering empirical questions. But thinkers in the past didn't have science's track-record to go on. Science as we know it today was still not in existence. And so, these thinkers from antiquity into the early modern period of philosophy tended towards a quasi-divinical, semi-mystical view of mathematics. They were, in other words, Platonists about mathematics.

I close this section with an interesting report. The cognitive scientist Donald Hoffman (2019) makes arguments, using evolutionary game theory, that imply that Plato was right—at least about mathematics.

Important Concepts

Decoding Plato

/plato-statue-outside-the-hellenic-academy-520346492-589ceaab3df78c475875af25.jpg)

Why Plato?

Why cover Plato at this juncture? Well, of course, Plato is integral to intellectual history. No introductory course to philosophy would be complete without some Plato. Here are some reasons for why it's important to know Plato:

Plato's views are an essential part of the history of Christianity and for that reason and essential part of Western history (see chapter 10 of Freeman 2007). By the middle of the second century CE, Christians began making use of Greek philosophy and “disentangling” the Christian teachings within it. Essentially, Christian intellectuals were selecting aspects of Greek philosophy that could be Christianized and discarding the rest. Clement of Alexandria, for example, claimed that God gave philosophy to the Greeks as a schoolmaster in order to pave the way for the coming of the Lord. Justin Martyr, a Platonist by training, believed could draw from both scripture and Greek philosophy to argue for its positions.

As it turns out, Platonism was ideally suited for providing the intellectual backbone for Christianity. Platonists were used to dealing with an immaterial world in which the Good is at the top of a hierarchy and where the material world is inferior to the immaterial world. This became the Christian views that God is the creator of all and that the material world is full of sin. Platonists also developed the idea of a soul that was independent of the body—an idea that Christians readily accepted into their doctrine. Importantly, Platonists taught that only a few could glimpse and come to understand the reality of the immaterial world, and this gave backing to the church’s hierarchy, where bishops understood God’s message and the rest had to rely purely on faith—something Protestants would take issue with centuries later.

As I've been stressing, it appears that Plato's views on the power of mathematics have been influential throughout intellectual history. Even if he was anti-positivist, it could be the case that Plato's emphasis on mathematics did pay dividends further down the line. In chapter 14 of his Worldviews, DeWitt reports that it is likely that Copernicus was inspired to work out his complex model of the solar system due to his Neo-Platonist leanings.

In Shenefelt and White (2003, chapter 2), the authors make the case that Aristotle's work on logic—i.e., the study of validity—took off for reasons other than the brilliance of the author. In particular, the social conditions were ripe for a study of that kind. Why was Aristotle’s audience so receptive to the study of validity? Because 5th century BCE Athenians made two grave errors that 4th century BCE Athenians never forgave: 1. They lost the Second Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE); and 2. They fell for “deceptive public speaking.” Aristotle's teacher, Plato, blamed both of those errors on a group of professional teachers of philosophy and persuasive speaking referred to as sophists. These first teachers were more pervasive in Athens than elsewhere due to the opulence of the city. But once public opinion turned on the sophists, things got violent. One person accused of sophistry (Socrates) was even put to death. And so the populace was ready to restore the distinction between merely persuasive arguments and truly rational ones. The study of the elenchus (persuasive argumentation) was divided into rhetoric and rational argumentation largely thanks to Plato. It was one step from here to standardize rational argumentation and study its logical form, which is what Aristotle did. As we will learn later, logic was a key ingredient in the digital revolution that we are currently experiencing.

But, to be honest, this is not the main reason why I bring up Plato here. I bring him up because Plato defended the view that we have an immaterial soul that existed before we were born. This is where he fits into our story. We are still trying to solve the Problem of Evil, and it would be helpful to overcome the Problem of Free Will. And so, we will attempt to defend the existence of souls. After all, souls are non-physical, and so they cannot be affected by the laws of nature. As such, determinism (or quantum indeterminacy) have no bearing on our souls. Our souls are free. That is, if we have souls, then they are free. So, here it is... DILEMMA #8: Do we have souls?

Although Plato's work ranges across many fields of inquiry, in this lesson we enter Plato's philosophical system through his views on mathematics.

With regards to mathematics, Plato believed that mathematical objects are more fundamental than physical reality itself. This means that mathematical objects are not mere ideas (conceptualism) and they are not merely physical objects (physicalism). Instead, mathematical objects exist independetly of humans; they are eternal and unchanging. Mathematical objects, in fact, are the basis on which physical reality is ordered. There is one level of existence higher than that of mathematical objects: the third realm, the realm of The Forms. The study of mathematics is the gateway by which we understand reality as it really is. This is called Platonism about mathematics.

Although Platonism about mathematics might sound strange to some, many of the thinkers we've covered so far seemed to have implicitly believed this.

We also covered various lenses by which one can interpret Plato, including as a solver of metaphysical puzzles, a math fanatic, a conservative reactionary, a mystic, an authoritarian, and a moral teacher.

FYI

Suggested Reading: Plato, Book VIII of The Republic

TL;DR:

-

School of Life, Plato and the Forms

-

School of Life, Why Socrates Hated Democracy

Supplemental Material—

-

Video: The Rugged Pyrrhus, Plato: The Republic - Book 3 Summary and Analysis

-

Reading: Catalin Partenie, Entry on Plato's Myths

-

Reading: Plato, The Allegory of the Cave

Related Material—

- Video: TEDTalks, Do we see reality as it is? | Donald Hoffman

Footnote

1. The sophists were probably more scholarly and less mercenary than Plato makes them out to be. For instance, sophists generally preferred natural explanations over supernatural explanations (i.e., positivism) and this preference might’ve been an early impetus for the development of what would eventually be science. Nonetheless, sophists would often argue that matters of right or wrong are simply custom (nomos). Although this view—which is called subjectivism—is a respectable view in ethics and aesthetics today, the sophists posited it in a somewhat crude way.