The Mind/Body

Problem

Are you not ashamed that you give your attention to acquiring as much money as possible, and similarly with reputation and honor, and give no attention or thought to truth and understanding and the perfection of your soul?

~Plato

What are we?

At the heart of the debate that we'll be covering today is a simple question: what are we? Some of you, if you don't think about it too much (but still try to answer the question), might suggest a variety of physical things, like your brain or maybe a part of your brain (not the whole thing). You're also unlikely to answer that you are your foot or your elbows. If you follow this line of reasoning, you probably believe that you are really equivalent to your mind, and your mind is in some way related to your brain. Even if you agree with the analysis so far, there are various competing materialist positions, materialism being the view that the brain is a sophisticated material thing that produces consciousness. Some thinkers even think that you are your brain plus your environment. On this view, having a brain isn't enough for being a self. You must react to your environment to be a self. You are necessarily a relational self; you obviously wouldn't be you without the environment that shaped you. See Olson (2007) to see just how many materialist positions there are.

"If we are indeed made of matter, or of anything else, we can ask what matter or other stuff we are made of. Most materialists say that we are made of all and only the matter that makes up our animal bodies: we extend all the way out to the surface of our skin (which is presumably where our bodies end) and no further. But a few take us to be considerably smaller: the size of brains, for instance. Someone might even suppose that we are material things larger than our bodies—that we are made of the matter that makes up our bodies and other matter besides" (Olson 2007: 4).

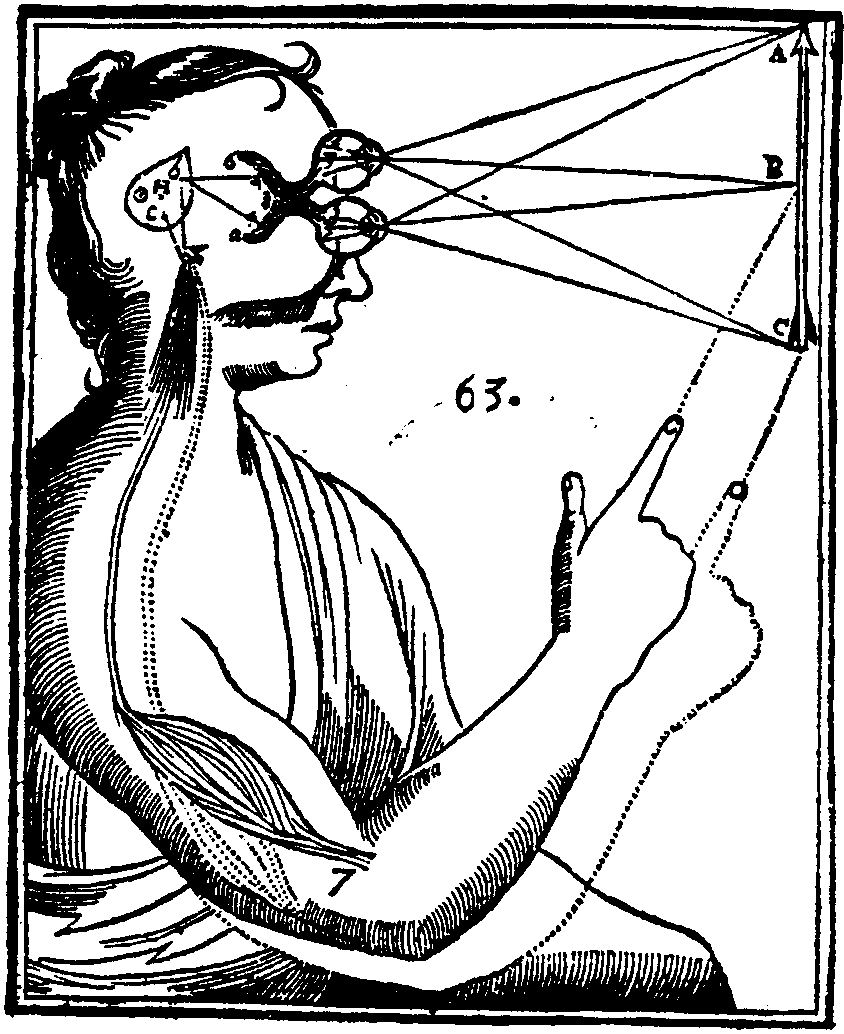

Diagram from Descartes' 1644

Principles of Philosophy.

But some of you reading this might take an entirely different type of position altogether. You think it is mistaken to look for your self in material objects like the brain. You believe that you are really equivalent to your soul. There is less disagreement, I suppose, on what a soul is. Better said, at least there's agreement on what a soul is not: it's not physical and it will not die when the body dies. If you believe that minds are really souls, in other words that there are physical things in the world but also non-physical souls, then you endorse a view called substance dualism. But dualism is not without its problems. Historically, the biggest challenge for and debate within the dualist camp is to give a satisfactory account of how the soul interacts with the body (see the Suggested Reading). Because these debates originated at a time when most of the relevant thinkers believed that the soul was the mind, these words were used interchangeably for them. This is why we refer to arguments that try to address the relationship between the soul and the body as arguments attempting to solve the mind/body problem.

Back to Plato...

Often times, people fail to see the relevance of Plato in this course, so I'd like to make it clear now. Plato and his theory of Forms leave us with a puzzle: how can we ever come to know the Forms if we've never seen them before? Forms are non-physical, so we can't see them with our eyes, but the way we experience the world appears to be with our senses. We need to see things to come to know them, and we can only see physical things! But Plato argued that, through the use of reason, we could come to know the true nature of reality. How?

Plato argued that we recognize the Forms because our souls existed before we were born. They existed in the same way in which the Forms exist. Let's call this Platonic Heaven. That is when we came to know the Forms: in Platonic Heaven. When we are born, we forget what we knew. And it is through the power of reason that we can recollect our knowledge of the Forms. In other words, we already know the truth; we just have to remember. We call this the argument from recollection. But the key component in Plato's theory is the belief in the existence of souls.

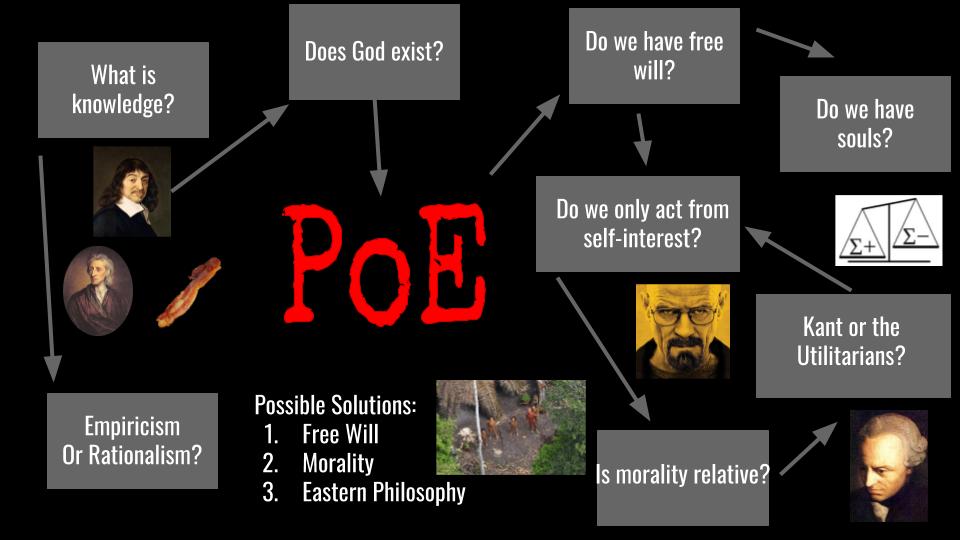

Notice for a moment how convenient it would be for us if Plato's theory is true. If there really are Forms then there really is a Form of the Good. This means we can solve Dilemmas #5, #6, and #7. These are all questions in the field of ethics, and once we've recollected the Form of the Good, we could dispense with these questions. We could also solve Dilemma #4 (Do we have free will?). This is because the main threat to (libertarian) free will we're covering comes from the laws of nature either determining our actions or making them random. But if we are fundamentally non-physical (i.e., if we are souls), then natural laws do not affect us. We are, in a sense, immune from the dictates of natural law. And so we are free. If we can defend (libertarian) free will, then that takes us a long way towards solving Dilemma #3 (Does God exist?). We could argue that many kinds of unnecessary suffering come from human free will. This would take much of the sting off of the Problem of Evil. If we could successfully defend God's existence, we could defend Descartes' view that reason is the foundation of all knowledge (Rationalism) over Locke's view that all knowledge comes from the senses (Dilemma #2). And lastly, we could solve Dilemma #1 (What is knowledge?); we can defend Descartes' foundationalism over Bacon's pragmatism and Locke's empiricism. We can finally escape the pit of skepticism.

What type of thing are we?

A valuable skill that is learned when studying Philosophy is to keep track of the different levels of analysis you are working on. The question we are asking now has to do with what type of thing we are. Put more bluntly: are we physical or non-physical? Are we souls or not? As we've seen, an answer in the affirmative can significantly affect all past problems covered in this course. This debate, then, will occupy us the rest of the lesson. Call this Dilemma #8: Do we have souls?

Decoding Dualism

Sidebar

There are some responses to the mind/body problem that are worthy of mention, although I believe they are only of historical significance. What I mean by this is that they do seem to, in a way, "solve" the problem, but I don't think that they are terribly convincing to anyone nowadays. Here's the general response. The argument that we're calling the mind/body problem is implicitly assuming interactionism about the soul and body. In other words, the primary assumption is that the soul and body can and do causally affecting each other. But this isn't the only show in town. Another option is occasionalism. Occasionalism is the view that mental states (in the soul) are caused by God and physical changes in the body (desired by the soul) are also caused by God. In other words, there is no interaction between the soul and the body; God creates in our souls experiences appropriate to whatever situation our bodies find themselves in and causes are bodies to do whatever our soul intends for our body to do. God is the causal go-between for body and soul.

But wait! There's more! According to the parallelism, our mental and physical histories are coordinated so that mental events (in the soul) appear to cause physical events (and vice versa); but mind and body are like two clocks that are synchronized so that they chime at the same time. In other words, God doesn't have to constantly act as a go-between. On this view, the body and the soul were designed so that they would align for their entire existence. Each are "pre-destined" to do as they do—no need for interaction!

Obviously, there's quite a few problems here. With regards to parallelism, this doesn't seem to leave much room for (libertarian) free will. As far as occasionalism goes, it is not an appealing solution because it seems to limit God's omnipotence. Why would God have to constantly be the go-between between body and soul? Couldn't God have somehow made it so that the soul can interact with the body without the need for constant divine intervention?

The existence of non-physical souls, a view called dualism, would be extremely convenient for the Cartesian foundationalist project we are attempting to defend in this course. It would both provide an avenue through which we can bypass the problem of free will as well as allow us begin to mount a counterattack to the problem of evil—giving us a fighting chance in refuting this argument against the existence of God.

Dualism, however, is mired with problems. Our subjective consciousness seems to be very much correlated with our physical brain, giving little credence to the view that we are fundamentally non-physical souls. Moreover, dualism seems to be functionally inert in that it cannot provide a mechanism through which the soul exerts an influence over the body, a challenge to the view which is called the mind/body problem.

What we are calling materialism stands in opposition to dualism. It is the view that consciousness is a product of purely physical things, including (but not limited to) the brain, its sensory organs, the autonomic nervous system, etc.

FYI

Suggested Reading: Andy Clark, Some Backdrop: Dualism, Behaviorism, Functionalism, and Beyond

-

Note: This file includes the Introduction, Appendix, and Chapter 1 of Andy Clark’s book Mindware. The suggested reading is the Introduction and the Appendix. However, Chapter 1 may be of interest to some students.

TL;DR:

-

Crash Course, Where Does Your Mind Reside?

-

TED-Ed, Are you a body with a mind or a mind with a body? - Maryam Alimardani

Supplemental Material—

-

Video: Closer to Truth, John Searle—Solutions to the Mind-Body Problem?

-

Video: Closer to Truth, Dan Dennett-What is the Mind-Body Problem?