The Trolley

(Pt. I)

That bodily pain and pleasure, therefore, were always the natural objects of desire and aversion, was, he thought, abundantly evident. Nor was it less so, he imagined, that they were the sole ultimate objects of those passions. Whatever else was either desired or avoided, was so, according to him, upon account of its tendency to produce one or other of those sensations. The tendency to procure pleasure rendered power and riches desirable, as the contrary tendency to produce pain made poverty and insignificancy the objects of aversion. Honour and reputation were valued, because the esteem and love of those we live with were of the greatest consequence both to procure pleasure and to defend us from pain. Ignominy and bad fame, on the contrary, were to be avoided, because the hatred, contempt and resentment of those we lived with, destroyed all security, and necessarily exposed us to the greatest bodily evils.

~Adam Smith, discussing Epicurus

Kant v. the utilitarians

Typically in an introductory ethics course, the view we learned about in the last two lessons is taught in tandem with the view we are covering today: utilitarianism (in particular the version of utilitarianism advocated by John Stuart Mill, 1806-1873). I tried to move away from that while introducing Kantianism, but now that we are moving towards utilitarianism, it's impossible to hide just how antagonistic these two views are to each other. It sometimes seems they are almost exact opposites in their approach to moral reasoning, and they disagree on almost every ethical issue of great import.

Why is this? There are many reasons. First, as you will learn in the Important Concepts, the utilitarians are explicitly moral naturalists. This is simply the view that moral properties are just natural properties. They're not commands from God or social constructs like the law. Instead, moral properties are empirically discoverable, i.e., capable of being studied by science. How? utilitarians believe that the moral property GOOD just is a positive mental state, namely pleasure. Pleasure, of course, is a natural phenomenon.1

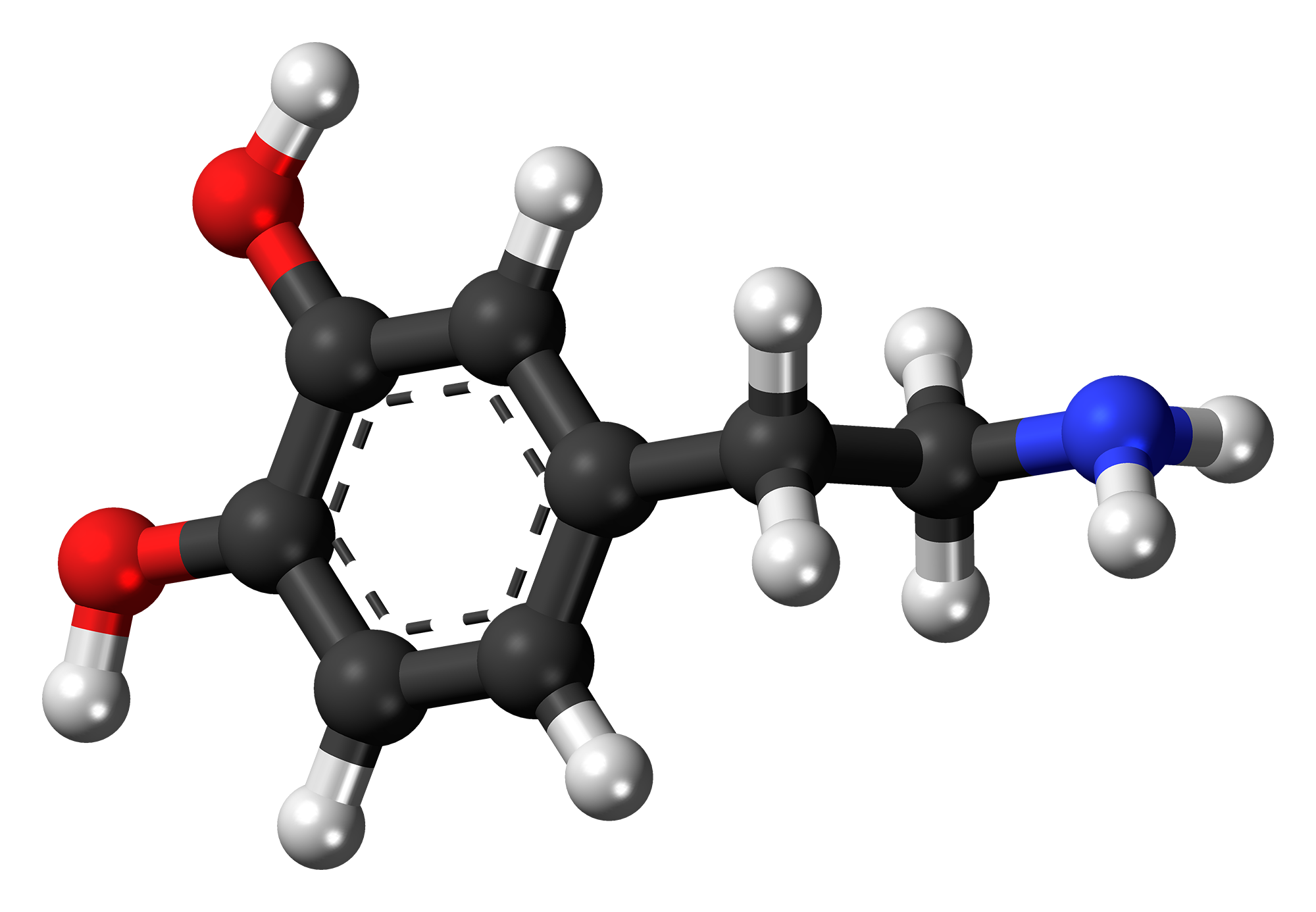

A dopamine molecule which

is discoverable through

science and is very much

unlike the synthetic a priori

truths of geometry.

Moreover, once they've opened up the natural realm as candidate for moral properties, they argue that positive mental states, hereafter referred to as utility, are actually the only intrinsic good. If you recall, ever since the lesson on Hobbes we've been referring to this view as hedonism. This is where the utilitarians' empirical approach comes in handy to them: they pose a challenge to non-utilitarians. What do you really want other than happiness (or the avoidance of pain, i.e., negative mental states)? The more "base" desires are obviously linked to the pursuit of pleasure and the avoidance of pain; I'm speaking here of our desire for things like sex and food. You might then claim you want a good job, a family, and a house. But the utilitarian would only inquire further, "Why do you want that?" Ultimately, you'd have to concede that having a bad job (or no job), no family, and no home would be considerably damaging to your mental wellbeing. Having them, however, would make you happy. Pretty much anything you desire, the utilitarian can find a way to show you that ultimately there is a desire for the utility that it brings you. This is why the utilitarians consider hedonism to be an empirical truth: you can discover that this is what really drives people by just asking them. That is, check the drives of humans, i.e., what motivates them, and you'll find that it is the pursuit of pleasure and/or the avoidance of pain; i.e., that hedonism is true. I might add that the utilitarians and Hobbes are far from the only hedonists. This view is famously advocated by Epicurus, as you can see in the epigraph above.

The combination of moral naturalism and hedonism already puts the utilitarians at odds with Kant, as well as with basically every other theorist covered so far. Recall that for Kant, the moral law was a synthetic a priori truth, a proposition that isn't merely an analytic truth (that's true by definition) but is justified independent of any sensory experience. In other words, for Kant, moral truth is arrived at through the power of reason. Reasoning is surely involved in utilitarianism too, but the justification will ultimately be a posteriori—based on some sensory experience.

Hedonism puts the utilitarians at odds with virtue theorists too. If pleasure is the only intrinsic good, then virtues cannot be a good in-and-of-themselves. Virtues, according to the utilitarian, are only pursued for the pleasure that they bring (or because being without them is distressing). Hear Mill:

“There is in reality nothing desired except happiness. Whatever is desired otherwise than as a means to some end beyond itself, and ultimately to happiness, is desired as itself a part of happiness, and is not desired for itself until it has become so... Those who desire virtue for its own sake, desire it either because the consciousness of it is a pleasure, or because the consciousness of being without it is a pain, or for both reasons united... If one of these gave him no pleasure, and the other no pain, he would not love or desire virtue, or would desire it only for the other benefits which it might produce to himself or to persons whom he cared for” (Mill 1957/1861: 48).2

In any case, the component of Utilitarianism that really puts it at odds with Kantianism is consequentialism. Recall from the lessons on Kant that consequentialism is the view that an act is right or wrong depending on the consequences of that action. Kantianism, on the other hand, specifically stipulates that you need not check the empirical realm. The moral law must be transcendental, independent of context, argues Kant. This might seem like a small difference now, but you'll soon see that this puts these two theories worlds apart—literally (according to Kant).

Much like classical cultural relativism wasn't explicitly formulated until the 20th century but had "hints" of it in ancient times, utilitarianism wasn't explicitly formulated until the 19th century by Jeremy Bentham but had antecedents both in ancient times (in the work of Epicurus) and in the 17th century in the works of Richard Cumberland (1631–1718), John Gay (1699–1745), Anthony Ashley Cooper, the 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury (1671–1713), and David Hume (1711–1776). It is interesting to note here how it appears that ages of great intellectual accomplishment are associated with utilitarianism. In the first place, and as we've already mentioned, the 17th and 18th centuries are associated with the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment, a time period that influenced the abovementioned thinkers.

With regards to the time period during which Epicurus lived, as well as the time period during which Epicureanism flourished, there is also evidence that it was one of intellectual breakthrough. In chapter 6 of The Closing of the Western Mind, Freeman discusses the intellectual merits of the first two centuries of the common era, as well as the increasingly pro-social role of the Roman emperor as the “parent” of the people. (Recall that by this point, Rome had conquered huge swaths of territory including most of Western Europe, as well as parts of the Mediterranean, North Africa, and the Middle East.) Freeman also discusses how it was a time of theological fusion during which the Romans co-opted foreign gods into their pantheon, the consequence being that across the empire there was a recognized hierarchy of gods—a supreme god at the head of other lesser deities. Freeman also discusses popular philosophies of the time: Epicureanism, Stoicism, and Platonism.

A map of the Roman Empire

in 125CE, during the reign

of the Emperor Hadrian.

In addition to noting that utilitarianism and its tenets (such as hedonism) can be associated with "enlightened periods", we might also note that there is nonetheless a change in the moral discourse from ancient times relative to that of modern times. Recall MacIntyre's distinction between Greek ethics and modern ethics. Greek ethics is concerned with the question, “What am I to do if I am to fare well?”; modern ethics is concerned with the question, “What ought I to do if I’m to do right?” As we learned last time, this transition was completed in the work of Immanuel Kant. The transition from the Greek to the modern approaches, though, can actually already begin to be seen after Aristotle. Aristotle and Plato, among others, had words for optimal behaviors in their particular social orders (e.g., arete). However, their social orders eventually fell prey to others. First, Athens fell to Macedon and eventually all were subsumed by the Roman Empire. And so, the words for these optimal behaviors remained but the behaviors themselves no longer led to thriving, since the social orders they were designed for no longer existed. This is actually what led to movements like Stoicism and the Epicureanism, movements that sought to redefine agathos under the new social order. The condition of the Greeks was now one of subordination. Unsurprisingly, these movements stressed a lifestyle that was conducive to either self-control with regards to one's private life (Stoicism) or withdrawal from excess desire (Epicureanism). These are no longer moral systems for being a successful statesman. These values are values for a conquered people. This is excellent evidence that moral norms change as social orders change, and that, depending on the social order, different moral norms stabilize and different moral discourses are shaped.

Making room...

Mill does not only differentiate his view from that of Kant; he also goes after other ethical theories. As you can see in his quote above, he argues that virtue theory doesn't hold any weight since it doesn't give the right theory of moral value. He claims that those who pursue virtue for its own sake are actually just pursuing pleasure or the avoidance of pain. Similarly, Mill goes after social contract theory. While reviewing the problems of past approaches to moral reasoning, Mill argues that social contract theory merely put a bandaid on the whole matter by inventing the notion of a contract. But he dismisses the theory outright. You'll get a better idea of why in the next section.

“To escape from the other difficulties, a favourite contrivance has been the fiction of a contract, whereby at some unknown period all the members of society engaged to obey the laws, and consented to be punished for any disobedience to them, thereby giving to their legislators the right, which it is assumed they would not otherwise have had, of punishing them, either for their own good or for that of society… I need hardly remark, that even if the consent were not a mere fiction, this maxim is not superior in authority to the others which it is brought in to supersede" (Mill 1957/1861: 69; emphasis added).

Important Concepts

The Theory

The Formula

The theory itself is simple. The Principle of Utility is derived by combining hedonism and consequentialism. It is as follows: An act is morally right if, and only if, it maximizes happiness/pleasure and/or minimizes pain for all persons involved.

Who counts as a person?

Here's another point of contention with Kantianism. Whereas Kant believe that personhood, i.e. moral rights, are assigned to anyone who is a Rational Being, i.e. able to live according to principles, Mill believed that all sentient creatures deserve rights. Sentience is the capacity to feel pleasure and pain.3

It should be added that setting the boundary for the moral community at sentience, the view endorsed by utilitarians, is not without controversy. Much like Kant's views are critiqued for not including non-human animals, the utilitarian perspective is also seen as too narrow by some. For example, some environmental ethicists believe we should extend the boundaries of the moral community to include bodies of water, the air, and perhaps even the planet as a whole (see Shrader-Frechette 2010/2003: 194-198).

For his part, Singer (2011: 123-124) believes the boundary of sentience is the most rational boundary. This is because our moral reasoning cannot be impartial about non-sentient things like trees, rivers, and rocks. If we were to try to imagine what it would be like from the perspective of the tree, there would just be a blank. And so, practically speaking, there is no difference in our moral reasoning whether we take the perspective of the tree or not. This is not to say that ecological considerations shouldn’t be incorporated into our reasoning. In fact, Singer is staunch advocate of environmentalism. However, Singer argues that it is most practical for us to allow our intuitions about environmental ethics to be guided by inhabiting the perspective of all sentient beings. By doing so and acting for the benefit of all sentient creatures, we would indirectly take care of the environment.

Subordinate Rules

Mill also endorses subordinate rules, or what we might call “common sense morality.” This is because it is unfeasible to always perform a Utilitarian calculus when making a moral decision in your day to day life. In any case, according to Mill, these are rules that tend to promote happiness. They’ve been learned through the experience of many generations, and so we should internalize them as good rules to follow. These rules include: "Keep your promises", "Don’t cheat", "Don’t steal", "Obey the Law", "Don’t kill innocents", etc. However, note that if it is clear that breaking a subordinate rule would yield more happiness than keeping it, you should break said subordinate rule.

“Some maintain that no law, however bad, ought to be disobeyed by an individual citizen; that his opposition to it, if shown at all, should only be shown in endeavouring to get it altered by competent authority. This opinion… is defended, by those who hold it, on grounds of expediency; principally on that of the importance, to the common interest of mankind, of maintaining inviolate the sentiment of submission to law” (Mill 1957/1861: 54).

Support

John Stuart and

Harriet Taylor Mill,

co-authors of

On the Subjugation of Women.

One of the reasons why Mill was dissatisfied with Hobbes' SCT is the reliance on psychological egoism, a view even earlier utilitarians had held. Mill, for his part, thought he could explain more with his view, namely the entire history of social improvement (see Mill 1957/1861: 78). In fact, you can devise a utilitarian justification for many of the great moral leaps forward in our history. For example, take the abolition of slavery. Sure, in the United States slaveholding states had to be defeated in a brutal civil war before American slavery was abolished. But in other countries, slavery was abolished in much less violent ways. An argument might be made for why slavery is wrong. It is wrong for one person (the master) to enjoy profit at the expense of the misery of several others (the slaves). The misery of the latter (the slaves) outweighs the utility enjoyed by the former (the master), so slavery is wrong. Similar arguments could be made for women's suffrage, the abolition of child labor, and the adoption of a vegetarian or vegan lifestyle (see Singer 1995/1975 for an argument for animal liberation).

You can even make utilitarian arguments against practices such as environmental contamination. Say that there is a paper mill which dumps its toxic waste into a nearby river. The owner could dump the waste more responsibly, but it would cost him a share of his profits. However, the river is the watersource for a nearby town, the members of which are becoming sick due to the contaminated water. The argument here would be that the utility enjoyed by the owner is outweighed by the pain felt by the sick and dying townspeople. This means that the practice of dumping toxic waste into the river is wrong.

An interesting use of utilitarian moral reasoning is featured in Mill's feminism—a topic that will arise again in Unit II:

"Like his eighteenth-century predecessor [Mary Wollstonecraft, (see footnote 4)], nineteenth-century philosopher John Stuart Mill argued that women need to become like men in order to become fully human persons. Mill noted that society's high praise of women's virtue does not necessarily serve women's best interests. To praise women on account of their gentleness, compassion, humility, unselfishness, and kindness is, he said, merely to compliment patriarchal society for convincing women 'that it is their nature to live for others', but particularly for men (Mill & Mill 1869/1911: 168). Thus, Mill urged women to become autonomous, self-directing persons with lives of their own; and he demanded that society give women all the rights and privileges it gives men" (Tong 2010/2003: 221).

Utilitarianism

Thought-experiments4

Challenging moral naturalism

Some thinkers have challenged the utilitarian naturalist assumption that the moral property of moral goodness could be equated with the natural properties of positive mental states. In Ethica Principia, G.E. Moore argued for moral non-naturalism, the view that moral properties cannot be studied with the natural sciences. He used various arguments (such as the naturalistic fallacy argument, which many think was insufficient), but the open question argument is the most often referenced. The argument goes something like this. If “good” just means “pleasure”, then we can express it like an identity claim:

Eg,

BACHELOR = UNMARRIED MALE

GOOD = PLEASURE

But it doesn’t seem like asking “Is a bachelor an unmarried male?” is the same as “Is good the same as pleasure?” The first is a silly question. But the second demands an argument in response. In essence, although some people consider moral naturalism to be intuitive, it still requires an argument in order to be truly established. This is a basic criterion that we have of all theories, whether they be scientific or philosophical.

Even moral skeptics, individuals who question whether there are any objective moral values (like someone who endorses the atheist version of DCT), are unimpressed by moral naturalism. Richard Joyce, a prominent moral skeptic, doesn't see the appeal in equating moral goodness with mental states. Clearly, this is an issue we'll have to revisit.

“When faced with a moral naturalist who proposes to identify moral properties with some kind of innocuous naturalistic property—the maximization of happiness, say—the error theorist [i.e., the moral skeptic] will likely object that this property lacks the ‘normative oomph’ that permeates our moral discourse. Why, it might be asked, should we care about the maximization of happiness anymore than the maximization of some other mental state, such as surprise?” (Joyce 2016: 6-7).

The theory is too demanding...

Lastly, just like some object that Kantianism is too strict, some object that Utilitarianism is far too demanding. For example, one might have to accept extremely unsavory social orders. Just like we saw Hobbes endorsing a form of enlightened despotism, where the ruler governs for the wellbeing of the subjects, Mill similarly endorses despotism as a legitimate mode of government in dealing with barbarians, as long as it ultimately leads to their improvement (see Mill 1989: 13). And so, Mill justified British occupation of India, although he objected to imperial misgovernment. In order to be justified, colonialism had to actually benefit the colonized peoples.

Enlightened despotism aside, consider now the most famous case of utilitarian dilemmas...

Two approaches to moral reasoning are naturally antagonistic to each other: deontology and consequentialism. Whereas Kant is an excellent representative of deontology, John Stuart Mill and his utilitarianism are a prime example of consequentialist thinking.

For Mill, what was morally required was what maximized happiness for all sentient beings involved, including non-human animals.

Mill, a member of Parliament, worked tirelessly in advocacy for women's rights, for the abolition of slavery, and for securing freedom of speech.

Mill's utilitarianism is not without controversy, however. If there are ultimately more positive consequences than negative, some unsavory actions might be justified, such as colonialism.

FYI

Suggested Reading: John Stuart Mill, Utilitarianism

-

(Note: Read chapters I & II.)

TL;DR: Crash Course, Utilitarianism

Supplementary Material—

-

Video: Julia Markovits, Ethics: Utilitarianism, Part 2

Advanced Material—

Reading: Julia Driver, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Entry on The History of Utilitarianism

Reading: Margaret Kohn and Kavita Reddy: Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Entry on Colonialism

Reading: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Entry on Utilitarianism, Section 3

Footnotes

1. I might add that the English word pleasure does not convey the complexity of positive emotions that J.S. Mill and other utilitarians mean by it. There is, Mill argues, a hierarchy of positive mental states. On the low end you might find the pleasure of sex, the satisfaction of a good meal, or the clarity of mind you have when you are well-rested. On the higher end you might find the fulfillment of a life well-lived or the equanimity of coming to terms with your own mortality. Mill famously put it this way in chapter 2 of his Utilitarianism: "It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied."

2. This conflict with hedonism and other moral systems has been obvious since ancient times. In The Theory of Moral Sentiments (part 7, section 2, chapter 2), Smith closes the chapter by contrasting the systems of Plato, Aristotle and Zeno with that of Epicurus. All agree, Smith shows, that virtue is the most suitable manner of attaining the objects of natural desire. In other words, they all have the same moral discourse and moral logic of the ancient world where being good is for the purpose of living well. For Epicurus, however, the only objects of natural desire were pleasure and the avoidance of pain; the others, however, found that knowledge, friends, country, etc., were valuable for their own sakes as well. Lastly, according to Smith, Epicurus did not make the case that virtue was an intrinsic good, i.e., good for its own sake, but the rest did.

3. I should add here that the meaning of sentience being used is one of several senses of the word. The word sentience is also used, for example, as a synonym for consciousness, more broadly speaking. We are not using the term in this way. When I use the word sentience it will exclusively refer to the capacity to feel pleasure and pain.

4. The thought-experiment that I am referring to as the Near and Dear Argument is just a stylized version of a thought-experiment made by the 18th century anarchist philosopher William Godwin in his Enquiry Concerning Political Justice. In this work, Godwin proposes that if you could only save one person, either a famous author or your father, that you should choose the famous author, since that person would make more people happy over the long run. On a historical note, Godwin was married to the feminist philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft and was the father of Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein. Wollstonecraft's brand of feminism will be covered in Unit II.