The Troublesome Transition

Life is pleasant.

Death is peaceful.

It's the transition that's troublesome.

~Isaac Asimov

Death with Dignity

It appears that disputes over the moral status of suicide can be found as far back as the First Intermediate Period of Egypt, circa 2181-2055 BCE (see Battin 2010: 674). Although that is a topic of importance and interest, in this lesson we will be focusing primarily on the moral status of assisted-dying in its various forms, glancing at issues surrounding suicide itself only briefly in the latter half of the lesson. Before looking at topics in the assisted-dying debate, though, let me say two things.

First off, it should be said that this is an extremely sensitive topic and that you should know that I will take precautions in presenting the material. Having said that, in essence, what we are discussing is ultimately suicide. This is clearly an important issue. So, if you are having any sort of suicidal thoughts, please reach out for help. One place to start is the Student Health Center. At the Student Health Center, the psychological services staff is available to talk confidentially with any student (with current ID) about the challenges with which they are faced. They do their work with the utmost respect for those who go to see them, without judgement. They will try to offer options and solutions that perhaps had not been considered. They will listen carefully to a student's problems and try to help find solutions to the everyday dilemmas that students confront. They are painfully aware that it can take a lot of courage to walk through the door of their facility to discuss personal issues. Click here for the ECC Psychological Services webpage.

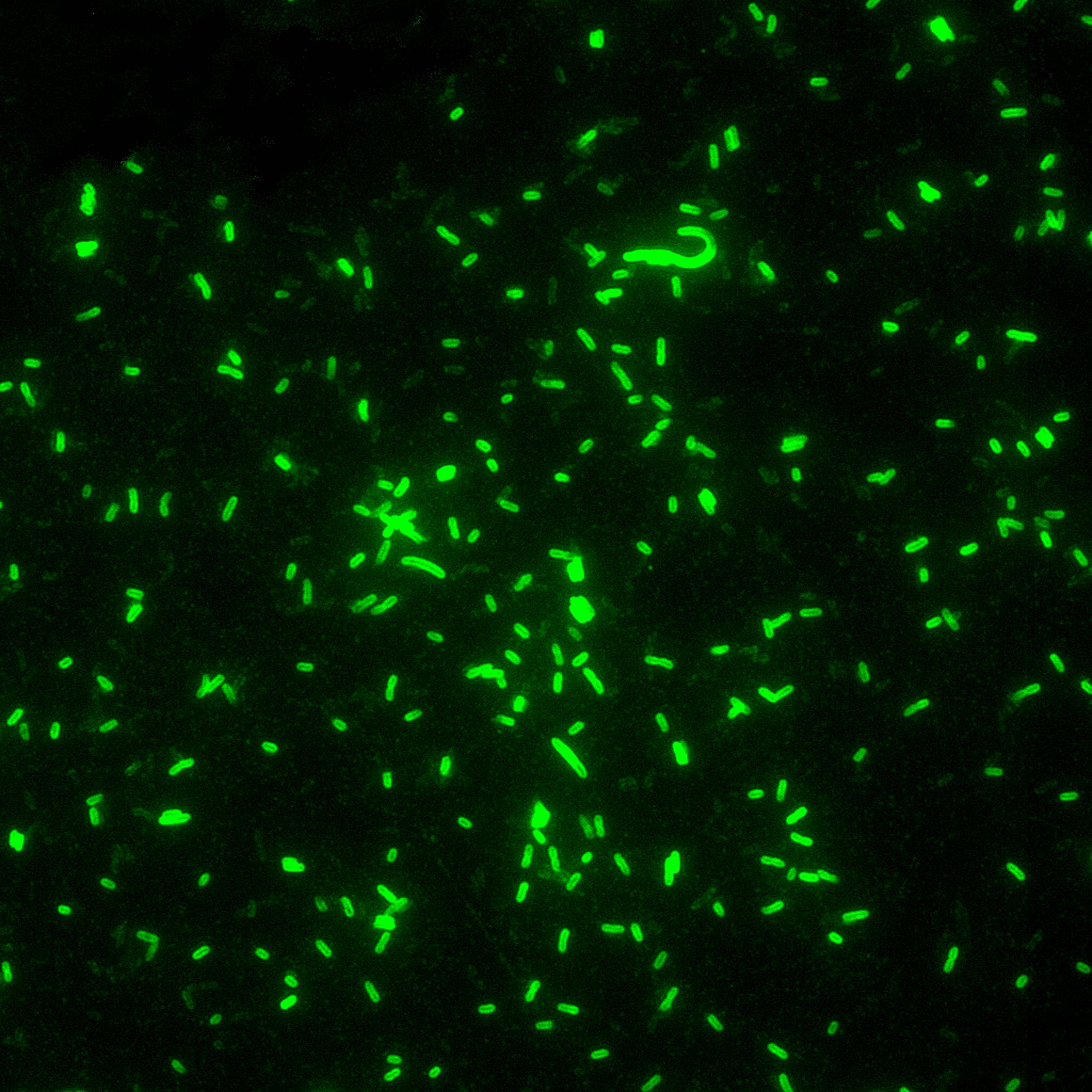

Yersinia pestis,

the bacteria which

causes plague.

Second, the fact that a debate surrounding assisted-dying even exists points to the immense progress that humankind has made in the past few centuries. For the majority of humans who have ever existed, death has been caused by factors such as parasitic and infectious diseases. For example, Winegard (2019: 2) provides the following statistic: “The mosquito has killed more people than any other cause of death in human history. Statistical extrapolation situated mosquito-inflicted deaths approaching half of all humans that have ever lived.” In chapter 2 of The Fate of Rome, Kyle Harper reminds us that in the Roman Empire life expectancy was about 30 years. He also notes that the fertility rate had to be very high, since otherwise the population could not be replenished generation after generation. In fact, a high fertility rate was so pivotal that the state actually penalized low fertility. Women had six children on average, although Mary Beard (2016) hypothesizes that the number might've been as high as nine. To add to this horror, it appears that people knew there was a season for death. This is because death came in waves throughout the year, depending on when the climate was most suited for disease ecology and mosquito-breeding (mosquitoes being the carriers of malaria). Even the great physician of antiquity Galen notes that most deaths came in the Fall.

Today, however, we are much more likely to die of degenerative diseases, such as heart disease and cancer—a time period Olshansky and Ault (1987) call The Age of Delayed Degenerative Diseases. Improvements in sanitation, antibiotics, immunization, and other breakthroughs in medical science have allowed humans to lengthen their lifespan substantially. In many developed countries, life expectancy is around 80 years. In other words, through medical science, humans have produced what we can call the terminal phase of dying. It is this stage of the life cycle that gives rise to questions surrounding the moral status of assisted-dying.

“On average, people die at older ages and in slower, far more predictable ways, and it is this new situation in the history of the world that gives rise to the assisted-dying issues to be explored here” (Battin 2010: 674).

Storytime!

Death with Dignity Laws in California

Important Concepts

Two arguments in favor of physician-assisted suicide

The argument from autonomy

Right-to-die advocate

Brittany Maynard (1984-2014).

A person, it seems, has a right to determine as much as possible the course of his or her own life. For example, in most Western-style democracies you are free to choose your career, what level of education you wish to complete, and who you want to engage with romantically—generally speaking.1 Since death is a natural part of the life cycle, it stands to reason that a person also has the right to determine as much as possible the course of his or her own dying. As such, if a person wishes to avoid the more painful stages of the terminal phase of dying, then they should have the choice for aid in dying such that it is safe (i.e., without unnecessary pain) and comforting (see Battin 2010: 676-77).

Although one might object that depression and other psychiatric disturbances might affect one's judgment near the end of their life (and specially if they have a terminal illness), those who advance the argument from autonomy argue that "rational suicide" is possible. As is stipulated in California law, two doctors would have to first determine that the patient is mentally-competent and has no more than six months to live. If the aforementioned criteria are met and it can be reasonably assured that a certain period of this terminal phase will be extremely painful, such as in the terminal phase of stomach cancer, then it seems perfectly rational to choose to avoid this phase.

The argument from the relief of pain and suffering

No person should have to endure pointless terminal suffering. If the physician is unable to relieve the patient's suffering in other ways and the only way to avoid such suffering is by death, then, as a matter of mercy, death may be brought about. Of course, there are such cases in the medical literature. As such, in those cases, physician-assisted suicide is morally permissible (see Battin 2010: 686-690).

A famous example of this form of argumentation comes from Rachels (1975). Rachels argues that current practices—that is to say current in 1975—which do not allow active euthanasia are based on a problematic doctrine, which Rachels calls the conventional doctrine. We should allow active euthanasia, Rachels argues, because this would decrease the hardship of those with terminal diseases.

Three arguments against physician-assisted suicide

The argument from the intrinsic wrongness of killing

The main premise in this argument is that the taking of human life is simply wrong. Suicide is the taking of one's own life. Hence, suicide is wrong. Moreover, assisting someone in suicide is assisting someone in taking a human life. Hence, assisting someone in suicide is also wrong (see Battin 2010: 678-681).

A reliable proponent of this argument throughout history has been the Roman Catholic Church. In the fifth century, Saint Augustine was the first to interpret the biblical commandment "Though shall not kill" as expressing a prohibition on suicide. Several centuries later, in the thirteenth century, Saint Thomas Aquinas developed an even more rigorous sanction against suicide. He argued that everything loves itself and seeks to remain in being. This renders suicide as wholly unnatural. Moreover, Aquinas argued, suicide harms the community and it is a rejection of God's gift of life. For all these reasons, suicide is wrong.

In 1958, Pope Pius XII issued a statement to anesthesiologists called "The Prolongation of Life" where he utilized the doctrine of double effect to make the case that physicians could use opiates for the control of pain—even if the use of these will cause an earlier death. The general idea behind the doctrine of double effect is that two or more effects might arise from a given action: the intended effect and a foreseen but unintended effect. In general, this doctrine is said to be applicable when 1. the action is not intrinsically wrong (such as relieving pain is not intrinsically wrong); 2. the agent must intend only the good effect, not the bad one (as when an anesthesiologist intends only to minimize pain and not necessarily to bring about an early death); 3. the bad effect must not be the means of achieving the good effect (as in anesthesiologists using opiates, as opposed to death, as a way to minimize pain); and 4. the good effect must be proportional to the bad one, meaning the bad effect does not outweigh the good effect.

The argument from the integrity of the profession

Fragment of the

Hippocratic Oath.

Another argument against physician-assisted suicide comes from reflecting on the nature of the medical profession. It is said that doctors should simply not kill; it is prohibited by the Hippocratic Oath. In other words, the physician is only allowed to save life, not take it (see Battin 2010: 681-82).

There is a common objection to this viewpoint, however. As it turns out, the Hippocratic Oath contained much more than the injunction to not take life. It also prohibits, for example, performing surgery and taking fees for teaching medicine. It would be inconsistent, one might argue, to insist that the injunction against taking life is legitimate, but that the parts about not performing surgery and taking fees can be safely ignored. Perhaps it could be argued that, as the practice of medicine was professionalized and became more strenuous to master, fees become reasonable. After all, there has to be incentive for mastering the art of modern medicine. It could also be said that surgery was a bad idea before germ theory. However, the response from the proponent of physician-assisted suicide would be the following: if the Oath can be modified to permit these new practices (i.e., surgery and fees), why not also permit assistance in suicide, in particular in those cases where the patient would simply suffer needlessly without the doctor's help?

The argument from potential abuse

Perhaps the best argument against physician-assisted suicide is the argument from potential abuse (Battin 2010: 682-86). It is telling that this argument is also known as the slippery-slope argument against euthanasia. Here is the gist. Permitting physicians to assist in suicide, even in those cases where it would greatly minimize pointless pain, may lead to situations in which patients are killed against their will. Once it is within the realm of possibilities for a doctor to terminate a patient's life, then either malicious agents or poor judgment might lead to a patient being unjustifiably killed. For example, perhaps a greedy relative might convince the terminal patient that it would simply be easier if they were to choose suicide. Or perhaps a terminal patient doesn't want to burden their family with more hospital costs or more emotional energy invested in a dying relative. Perhaps a doctor will, via unconscious racial prejudice, disproportionately advocate end-of-life assistance to certain races and not others. And, of course, there are countless other possible scenarios, all of which suggest that allowing for physician-assisted suicide is a slippery slope that will eventually include some unjustifiable deaths.

The advocate of physician-assisted suicide could respond that there should be a basis for these ominous predictions before such an argument can hold any water. Having said that, there are some bases for these predictions. Medical care in the United States is, I would say, unreasonably costly. Cost pressures alone might lead to some of the aforementioned situations. Even if cost could be somehow ruled out, we know that greed, laziness, insensitivity, and prejudice all exist. In other words, these are genuine risks that we must be candid about.

Food for thought...

Ultimately, a key issue behind the debates surrounding physician-assisted suicide is the permissibility of suicide itself, independent of whether it is assisted by a physician or not. Here's an important question to ponder. Proponents of assisted suicide assert that autonomy, i.e., one's right to determine as much as possible how the course of one's life is to proceed, is a fundamental good that must be protected. However, they advocate an act that extinguishes the basis of autonomy. In other words, to choose to end your life is a choice that ends the capacity to make any future choices. Is this inconsistent? Do we really have a right to choose to end our ability to choose?

John Stuart Mill might've said that the advocates of physician-assisted suicide are being inconsistent. Again, this debate did not arise until the 20th century, so Mill did not directly comment on the issue. However, some commentators believe he would've sided against physician-assisted suicide. After all, we do know that Mill made a case against voluntary slavery, i.e., giving yourself over to a master in order to acquire food and shelter. Perhaps this is analogous to physician-assisted suicide?

“The same conundrum prompted John Stuart Mill, a stalwart champion of individual liberty, to favor legal proscription [i.e., banning] of voluntary slavery. Mill claimed that an individual cannot freely renounce his freedom without violating that good. Similarly, autonomous acts of assisted suicide annihilate the basis of autonomy and thereby undermine the very ground of their justification” (Safranek 1998: 33; interpolations are mine).

Kant is a little easier to figure out. Kant is definitely against suicide.

“When discussing how the formula of humanity entails the perfect duty to refrain from suicide, Kant writes: [T]he man who contemplates suicide will ask himself whether his action can be consistent with the idea of humanity as an end in itself. If he destroys himself in order to escape from a difficult situation, then he is making use of his person merely as a means so as to maintain a tolerable condition in life. Man, however, is not a thing and hence is not something to be used merely as a means” (Manninen 2006: 102).

Lastly, David Hume thought otherwise. Although Hume argues that to leave behind any dependents in a vulnerable state is not permissible, he generally thinks that “A man who retires from life does no harm to society: he only ceases to do good, which, if it is an injury, is of the lowest kind.” He also stresses, however, that “small motives” are not sufficient for someone to “throw away their life.” In other words, it's wrong to commit suicide if you are leaving family members and other dependents behind with no one else to care for them. But, if this is not the case, Hume finds suicide generally acceptable (if it is freely chosen). I hasten to add, however, that "small motives", Hume argues, are not a good enough reason for suicide. Hume's views will be covered in the next unit.

Dying well

Perhaps it's fitting to end here with a discussion of a much neglected (and even actively avoided) topic: the need for learning how to die well. Considered one way, we can see life as a series of skills that must be mastered. As a toddler, you learn to walk and talk. As a child, you learn basic skills and your role in the family structure. As a teenager, you begin to discover more about yourself and (hopefully) you skillfully discern your different strengths and weaknesses, acknowledging each in a truthful way. As a young adult, you learn your craft, the skill that will earn you your livelihood. Later, you may become a parent and you must learn the skill of parenting. Some of us, as our parents age, must learn the skill of caretaking. If you get married, you must learn the skill of becoming a good partner. As you age, you must learn to let go of some habits that are no longer suited for you. And ultimately, of course, you must prepare for death—the last skill you must learn.

Mortality is something we must all face, and on this topic we can glean great insight by past moralists. In his inspiring How to Think Like A Roman Emperor, Robertson (2019) surveys the Stoic practice of Marcus Aurelius. Although most Stoic writings are lost, we do understand their basic views: you must live in accordance with nature. This was synonymous with living wisely and virtuously. As we know, the Greek word arete is actually best translated not as “virtue” but as “excellence of character.” Something excels when it performs its function well. And so, humans excel, the Stoics argued, when they think clearly and reason well about their lives.

This is easier said than done, of course. There are many factors that might cloud our judgment and not allow us to think well. The Stoics had methods for countering these obstacles. For example, Robertson gives an excellent summary of Stoic views on language. The Stoics thought that language was important not only in how you portray the world to others, but also in how you portray the world to yourself. You should develop a rich vocabulary, and you should always strive for clarity. Importantly, Stoics acknowledged that humans tended to exaggerate and/or paint events and interactions with others through a moral lens. Stoics argued that we should strive as much as possible to portray events in a purely descriptive sense, without exaggeration and without loading our phrases with value judgments. In other words, instead of framing an argument you had with a loved one in a way that's loaded with moral terms like "manipulative" and "unforgivable", as well as exaggerations like "You always...", you should try to describe the event to yourself (and others) with only the facts. Present to yourself reality without making yourself a victim (or a villain!). Just state the facts, and this will allow you to get a better handle on the situation. Words, especially the words you use in framing a situation, do matter.

The most helpful Stoic teaching, in my opinion, is the Stoic ideal of cognitive distancing. Re-frame your situation to lessen its intensity. If you find yourself in a disagreement with a friend, try to take their perspective. If you find yourself riddled with anxiety, focus only on those issues that you have control over (instead of worrying about things over which you have no control), make a reasonable plan of action and execute it. Accept your troubles as an opportunity to practice your Stoic ideals.

With regards to mortality, the Stoics had a very important practice, one that is enshrined in a phrase: memento mori. This phrase, which is translated as "Remember that you are mortal", was a part of daily Stoic practice. Stoic practitioners saw death as a natural part of the life cycle and, as such, tried to prepare themselves for it by reminding themselves daily of their mortality. By doing this, they reminded themselves that time could not be wasted. We must prioritize our actions. We must engage in those activities that are truly important to us, even if they are difficult. It's highly unlikely that, on their deathbeds, most people think to themselves that they should've watched more Netflix. Instead, they probably wish they would've spent more time with their loved ones; they wish they would've taken that trip, hugged their spouse more often, or finished that degree. They regret not apologizing more and they regret not being more forgiving. They may even regret not having enough time to prepare for a good death. Memento mori.

Barking (Jim Harrison)

The moon comes up.

The moon goes down.

This is to inform you

that I didn’t die young.

Age swept past me

but I caught up.

Spring has begun here and each day

brings new birds up from Mexico.

Yesterday I got a call from the outside world

but I said no in thunder.

I was a dog on a short chain

and now there’s no chain.

The debate surrounding physician-assisted suicide arose only in the 20th century, as degenerative disease became the predominant cause of death in the developed world.

Two arguments for the permissibility of physician-assisted suicide are the autonomy argument (which states that we have a right to determine the course of our lives, including our death) and the argument from the relief of pain and suffering (which states that physician-assisted suicide is permissible since it minimizes pain/suffering).

Three arguments against the permissibility of physician-assisted suicide are the argument from the intrinsic wrongness of killing (which states that killing, including killing yourself, is always wrong), the argument from the integrity of the profession (which states that suicide is not in the purview of the medical field), and the argument from potential abuse (which states that allowing physician-assisted suicide might have negative consequences down the line).

The forms of moral reasoning involved are as follows:

- The fundamental motivation behind the argument from the relief of pain and suffering, as well as Rachels (1975), was the minimization of suffering. This is consequentialist reasoning. In fact, some utilitarians go as far as permitting non-voluntary active euthanasia if it will decrease overall suffering (see Singer 1993). Interestingly enough, the argument from potential abuse (a.k.a. the slippery slope argument) is also a form of consequentialist reasoning, albeit on a wider scope.

- Concerns over terminally ill patients being used as a means to an end (as in manipulation and coercion) and lack of universalizability (as in where the costs of end-of-life medication might be prohibitive to some) are deontologic concerns. In other words, these are violations of Kant’s categorical imperative.

- Concerns over violating the function of a doctor are Aristotelian concerns. In other words, bringing a life to an end is not conventionally seen as an action flowing from a good doctor.

FYI

Suggested Reading: James Rachels, Active and Passive Euthanasia

Supplementary Material—

- Video: Crash Course, Assisted Death & the Value of Life

Related Material—

-

Video: The Last Word with Lawrence O'Donnell, Brittany Maynard's death with dignity

Book Chapter: Donald Robertson, The Contemplation of Death

Advanced Material—

-

Reading: Peter Singer, Taking Life: Humans

-

Reading: Franklin G. Miller and Howard Brody, Professional Integrity and Physician-Assisted Death

-

Reading: John Safranek, Autonomy and Assisted Suicide: The Execution of Freedom

Footnotes

1. An interesting exception to the first two is the three-tiered educational system in Germany.