The Wisdom of Psychopaths

Nothing in the world is harder than speaking the truth and nothing easier than flattery. If there’s the hundredth part of a false note in speaking the truth, it leads to a discord, and that leads to trouble. But if all, to the last note, is false in flattery, it is just as agreeable, and is heard not without satisfaction. It may be a coarse satisfaction, but still a satisfaction. And however coarse the flattery, at least half will be sure to seem true. That’s so for all stages of development and classes of society.

~Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Argument Construction

Great Violence

By this point you've been exposed to and studied over a dozen arguments. It's worth taking time to reflect on the nature of philosophical argumentation. Recall that if an argument is valid, then the premises force the conclusion upon you. In other words, if you accept the premises as true and the conclusion does necessarily follow from these premises, then you must accept the conclusion. Notice that there is a violence to argumentation. Things are "forced" upon you and you "must" accept them. Things are no different when you are responding to, say, analogical arguments. If someone makes an argument to you by way of analogy, the way to undermine their position is by breaking the analogy. If you are successful, you have refuted their argument—the term refute coming from the Latin refutare, which means "to repel".

Forcing beliefs upon someone, breaking their analogies and repelling their conclusions—these are not friendly endeavors. But now that it's time to construct your own arguments, you must psychologically prepare yourself to impose your views on another, rational as they may be. Here are some simple guidelines:

An individual

with a history

of violence.

When you are constructing an argument, be sure to walk the reader through every step of your reasoning. This is harder than it seems. We make many assumptions that we are not consciously aware of when we arrive at our beliefs (if we do in fact arrive at our beliefs in some sort of rational way). Your task is to think about and discover all these small assumptions that you make. Make them explicit first. Then defend them. Make it so that you walk the reader—although perhaps "push" is a better word—down your train of thought, making them accept all your assumptions along the way, so that, when you arrive at your conclusion, they are forced to accept it. Give them no elbow room. Make them walk in a straight line, all the way to your view.

Use logical indicator words, like "if...then", "and", and "or". Using "if...then" chains is extremely helpful. Someone who believes in A will be forced to believe D if you first show them that "If A then B", then "If B then C", and finally "If C then D".

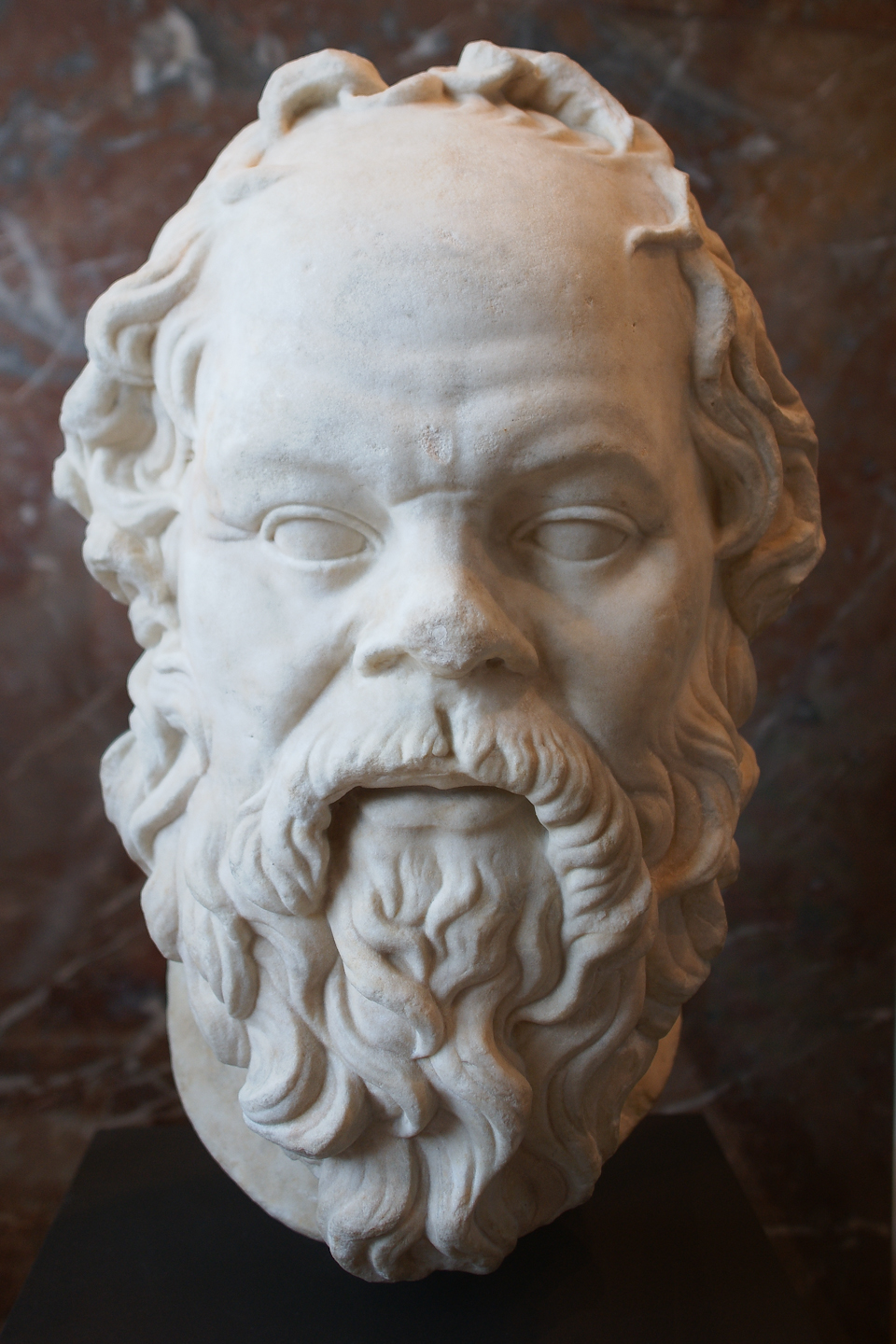

Be very specific in your claim. Disambiguate what you're saying as much as possible. Do not(!) leave room for misinterpretation. A master of dialectic argumentation, Socrates, showed that if you have any holes in your argument a good critical thinker will find them. Per Herrick (2015), Socrates' favorite questions were basically "What do you mean by that?" and "What's your evidence for that?" If you are unclear about what you mean, you leave yourself vulnerable to refutation.

Argue for every single part of your argument. Don't assume that some general claim that you make is widely accepted. Apparently, people fall into this trap all the time (see the Cognitive Bias of the Day). So watch out!

Lastly, use only the best evidence. If you find your support from some news website that no one's ever heard of before, then these will be weakly-supported premises. Chances are that your opponents will have these weak premises in their crosshairs. Don't let your whole argument hinge on these weakly-supported premises. Get rid of them. Have only strong premises. Use peer-reviewed articles. Use books that are published by publishing houses based in universities. Whenever possible, ensure that there are multiple corroborating sources, i.e., try to find multiple sources that support your claim. (By the way, if you can't find good support for your view, ask yourself if you might be wrong, or at least wrong-headed, in your inquiry. Maybe your position is wrong? Maybe you're not being specific enough? Maybe there isn't good data on this issue because it is hard to study? Critical thinking isn't about defending your views no matter what; it's about having a method for distinguishing between claims that are likely to be true from those that are likely to be false. This process of demarcating the true from the false applies to our own views as well.)

Case Study

One of my favorite examples of crafty argumentation comes from LaFollete (1980; see the FYI section). In this paper, LaFollete argues that parents should require parenting licenses. How did he arrive at his conclusion? Here's his reasoning. His initial assumption is this: any activity that is potentially harmful to others and requires certain demonstrated competence for its safe performance ought to be regulated. It seems very difficul to disagree with this. For example, one way of looking at a car is as a two ton weapon. Of course, we require that drivers pass a minimum competency test before they can legally get behind the wheel. Moreover, if someone is caught behind the wheel without a license, there are fines and potential jail time. The same goes for firearms. Clearly firearms can be dangerous both to the gun owner and those around him/her. Intuitively, LaFollete would argue, there should be some regulation about who can own firearms. By the way, it looks like most Americans agree that there should at least be universal background checks if one wants to own a firearm. LaFollete continues. If we also have a reliable procedure for determining whether someone has the requisite competence, then the action is not only subject to regulation but ought, all things considered, to be regulated. In other words, if we do have some kind of test or assessment that can distinguish between those who are, say, competent drivers or weapons-carriers and those who are not, then it seems like it is optimal to use this test.

With these two assumptions established, LaFollete makes the claim on which the whole argument rests: parenting can be harmful to children. Although this may be obvious, one should still defend this claim. Unfortunately, there is plenty of evidence that parents have harmed their children, even without knowing it. For example, Heimlich (2011) documents cases of religious child maltreatment, i.e., instances of psychological and physical harm inflicted on children by their parents for religious reasons. Heimlich mentions these examples of maltreatment, among others: withholding necessary medical treatment (which resulted in death), psychological abuse through fear-based parenting and religious practices, and physical abuse (resulting in death) due to belief that a child is possessed by a demon. This is both depressing and excellent support for LaFollete's claim. Of course, it doesn't even have to be this extreme. There are many instances of parents harming their kids, whether it be through neglect, physical abuse, or psychological torment.

LaFollete then argues that a parent must be competent if he or she is to avoid harming his/her children. Moreover, even greater competence is required if he/she is to do the "job" well. But not everyone has this minimal competence (as was argued for in the previous paragraph). Beyond child abuse, many people lack the knowledge needed to rear children adequately. Many others lack the requisite energy, temperament, or stability. In short, good parenting is hard.

Now here's the punchline. We actually do have tests for distinguishing between who is a minimally competent parent and who is not: the licensing process for adoption. Adopting a child appears to require some persistence. The process can take up to a year, per LaFollete, and it is somewhat invasive, since adoption agencies have to make sure your home is safe for a child. Of course, the irony is that "natural" parents don't have to go through any of this. LaFollete makes the claim, which by this point seems less bold, that "natural" parents should also require a license—not just adoptive parents.

Here's his argument in standard form:

- Any activity that is potentially harmful to others and requires certain demonstrated competence for its safe performance, ought to be regulated (e.g., driving a car).

- Parenting is potentially harmful to others, namely children.

- Moreover, parenting requires certain demonstrated competence for its safe performance—safe for the children that is.

- Therefore, parenting ought to be regulated.

- Further, if there is a reliable procedure for determining whether someone has the requisite competence to perform some action that is being regulated, then the action ought to be, all things considered, regulated using this reliable procedure for determining whether someone has the requisite competence to perform said action—or something like this reliable procedure.

- There is a reliable procedure for determining whether someone has the requisite competence to be a parent, namely the adoptive parent licensing process.

- Therefore, biological parenting (along with adoptive parenting) should be regulated using this reliable procedure for determining whether someone has the requisite competence to rear a child; i.e., there should be parent licensing.

Activity for the reader: Analyze this argument!

Argument Extraction

Note: The following views are those expressed by Dutton (2012). He has one (very popular) way of characterizing psychopathy, but it is not the only one. There have been different, contradictory conceptions of psychopathy have been used throughout history. For more info, see Skeem et al. 2011.

The Wisdom of Psychopaths

In The Wisdom of Psychopaths, research psychologist Kevin Dutton advances a controversial thesis: the functional psychopath hypothesis. His view is, in effect, that in some contexts psychopathic traits can be advantageous. In other words, there are situations and social roles in which psychopaths excel, to the benefit of those around them. This idea ruffles all kinds of feathers, since we've been taught to think psychopaths are the worst of the worst. So, to understand Dutton's hypothesis, let's begin with some context.

First off, Dutton tries to get at just what psychopathy is. He notes that there are some neural abnormalities in psychopaths. For example, normal brains (i.e., the brains of non-psychopaths) tend to react quickly to emotionally-laden words, like “cancer”. Thus, these neurotypical brains tend to recognize these emotionally-laden words more quickly. Psychopaths, however, don’t. Apparently, the emotional processing parts of the brains of psychopaths do not work as they do for non-psychopaths. In other words, psychopaths don't feel emotions as strongly as non-psychopaths—sometimes not at all. For this reason, psychopath brains don't recognize emotionally-laden words as quickly. They read them just as they would any other word, like "dog" and "bus". They remain cool and collected, even under emotionally-charged situations—a skill Dutton notes might be good for a surgeon.

Second, psychopaths appear to have special psychopath powers—and I'm only slightly kidding about this. For example, psychopaths seem to be better at recognizing vulnerability from the way a person walks, via their gait. A gait is a person's pattern of walking. And just by watching how someone walks, individuals who score high on a test for psychopathy can guess who's more emotionally fragile and vulnerable. Also, interestingly enough, psychopaths are better at faking emotions. They can also sense when someone is hiding something—a skill Dutton muses might be good for a customs agent.

By the way, just like psychopaths can pick out the weak among the general population, the general population also seems to have a psychopath radar. Those who have had confirmed contact with psychopaths, e.g. those who have had close encounters with serial killers, attest to a feeling of dread that comes over them. Why would we evolve this psychopath radar? Dutton reviews one theory from evolutionary game theory that might provide an answer. The theory hypothesizes that psychopathic traits might be adaptive to certain groups. In other words, having individuals with psychopathic traits in a group might be advantageous to the group as a whole, since they would excel in essential tribal activities (like war and hunting). (This theory, I might add, is advocated by none other than Robin Dunbar, the famous British anthropologist and evolutionary psychologist responsible for the idea behind Dunbar's number.) So, psychopaths might be useful for social groups. But, of course, these same psychopaths could also be a menace to society, since they are capable of killing without remorse. One example of this sort of individual that Dutton brings up is the berserker from Nordic cultures. These berserkers would apparently go into an uncontrollable rage during battle and kill everyone around them, both enemies and allies. In any case, as a result of having individuals with psychopathic traits within their group, although group members need some psychopaths in their group, they also need to know who they are—to protect themselves. Hence, we developed a sense for detecting psychopaths—or so goes the theory.

So how is being a psychopath advantageous in today's society? Before fleshing out his idea, Dutton moves to disentangling antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) from psychopathy, two personality disorders which were considered synonymous at the time he was writing. He makes the case that a hallmark of ASPD is socially-deviant behavior, while the hallmark of psychopathy is affective impairment, i.e., non-normal emotional processing. So, in layman's terms, the defining characteristic of people with ASPD is that they violate social rules, while what distinguishes psychopaths is that they simply don't process emotions like the general population. In fact, not only do psychopaths not(!) show emotional arousal in very emotionally-charged situations, some subjects even show a decrease(!) in heart rate when engaging in risky or violent behavior. So, it is not necessarily risky or violent behavior that sets apart psychopaths from the rest; it is their lack of emotionality.

Neil Armstrong,

total psychopath.

Quick aside: It might be the case that the psychopaths that are most famous also have ASPD. If, according to some estimates, psychopaths make up around 1% of the population, then it is only a small fraction of this %1 that you have to worry about: those that are both psychopathic and have ASPD. As an aside to this aside, it almost seems it's an even smaller fraction of psychopaths that we have to be weary of, since to be the kind of secret sadistic killer that we are afraid to fall prey to, these individuals have to have both psychopathic traits and ASPD, as well as high intelligence, imposing physical strength, and perhaps even charisma. Only with this constellation of traits can one truly be an enormous covert threat to society, like some famous serial killers.

So, here is the functional psychopath hypothesis. There are emotionally-charged social situations where being in control of your emotions, being able to remain calm and collected, is clearly advantageous. These roles include that of surgeons, police officers, customs agents, lawyers, and even athletes. Psychopaths have this ability to remain calm. Thus, they are disposed to performing these social functions well, since they can keep a clarity of mind during the task at hand.

So Dutton's hypothesis becomes more clear: being a psychopath isn’t in and of itself a leg up in society. It is only in certain social roles where being a psychopath might be advantageous. Dutton hastens to add, however, that psychopaths are well-represented in the class of CEOs. He reports on the work of Board and Fritzon, two researchers who found a higher proportion of psychopaths among the CEOs they surveyed than among the inmates they interviewed. In other words, according to these researchers, there's a higher percentage of individuals with psychopathic traits in board rooms than in prisons. Clearly being calm and collected pays dividends. This finding helps Dutton refine his hypothesis further. The type of psychopathy that is ideal is one that is in the moderate range: too psychopathic and you have no impulse control; too non-psychopathic and you don’t get the benefits, e.g., remaining cool-headed so that one can recognize and take advantage of high-payoff risks and keeping calm during emotionally-charged situations.

In closing, there might actually be some famous hero psychopaths. For example, Dutton makes the case that perhaps even Neil Armstrong, the first man on the moon, was a psychopath. According to logs of the Apollo 11 mission, Armstrong and his team were very close to a violent, lonely space death multiple times when attempting to safely land on the moon. But through it all, Armstrong appeared to remain completely unmoved. This complete imperturbability is, of course, the classic psychopathic trait.

- Read from 571a-583a (p. 270-284) of Republic.

- Complete Quiz 3.5+.

There is a sort of violence to argumentation.

When you are constructing an argument, be sure to walk the reader through every step of your reasoning. Use logical indicator words and be very specific about your claims. Argue for every single part of your argument using only the best evidence.

Psychopathy, which is distinguished from antisocial personality disorder (ASPD), is associated with decreased emotional processing. Psychopaths are also better than the general population at recognizing vulnerability, faking emotions, and sensing when someone is hiding something.

Per Kevin Dutton, there are emotionally-charged social situations where being in control of your emotions, being able to remain calm and collected, is clearly advantageous. These roles include that of surgeons, police officers, customs agents, lawyers, and even athletes. Psychopaths have this ability to remain calm. Thus, psychopaths have a disposition which might allow them to perform these roles well.

FYI

Suggested Reading: BBC, How to build an argument

TL;DR: CrashCourse, How to argue

Supplemental Material—

-

Reading: The Writing Center (UNC), Argument

-

Video: Big Think, Inside the brains of psychopaths | Kevin Dutton, James Fallon, Michael Stone

-

Reading: Hugh LaFollete, Licensing Parents

Related Material—

-

Video: Big Think, Are You a Psychopath? Take the Test! | Kevin Dutton

-

Video: TEDTalks, Robin Dunbar - Can the internet buy you more friends?

Advanced Material—

-

Reading: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Entry on Argument

-

Video: The Royal Society, Why do some people become psychopaths? | Essi Viding

For full lecture notes, suggested readings, and supplementary material, go to rcgphi.com.