Towards Kallipolis

Educate the children and it won't be necessary to punish the men.

~Pythagoras

Where to begin?

If one is discussing normative questions relating to children and childhood, it's difficult to not begin with the topic of abortion. This is because if children really do have full-fledged moral rights, a view that we will explore in the next section, we must begin the discussion by isolating the origin point of those moral rights. In other words, we have to figure out when moral rights start, the point at which one becomes a member of the moral community.

Before beginning, perhaps a few things should be said about the concept of moral personhood itself. Recall that the two most explicit accounts of moral personhood we've explored in this course are those that attribute personhood to individuals with certain intellectual capacities, such as Kant, and those that award moral rights to those with the capacity for certain feelings, such as pleasure and pain on the utilitarian account. Although the former account, the one having to do with intellectual capacities, is most closely aligned in our course with Immanuel Kant, Kant is not the only advocate of this approach. In his Essay Concerning Human Understanding, the philosopher John Locke gave his account of what a 'person' is. He wrote that a person is a "thinking intelligent being, that has reason and reflection, and can consider itself the same thinking thing, in different times and places" (Locke as quoted in Harris and Holm 2010: 115). As you can see, Locke clearly emphasizes our capacity to recognize ourselves as the same person throughout time and in different contexts if we are to be deserving of moral rights. It is interesting to note that, on this account, perhaps even machines can be in principle awarded moral rights, if they have the right capacities—a topic near and dear to my heart. Also interesting is how this view of personhood explains the mechanics behind moral wrongs: the wrong done to an individual when their existence is ended prematurely is the wrong of depriving that individual of something that they value (ibid., 116).

With regards to abortion, an advocate of a view somewhat like this is Mary Anne Warren. Warren's views seemed to have changed throughout time, and she will be mentioned again in the lesson titled The Jungle. However, in her 1973 article, where she argues against the opponents of legalizing abortion, she advocated a view somewhat similar to that of Locke.1 Her argument is that opponents of abortion commit one of two errors in reasoning. Either they presume that a fetus has rights without proving it (a fallacy called begging the question) or they argue for fetus rights through equivocation, which is when you use a word with one meaning in one premise and then use the same word utilizing a different meaning in a different premise. Here is the standard pro-life argument, according to Warren:

- It is wrong to kill innocent human beings.

- Fetuses are innocent human beings.

- Therefore, it is wrong to kill fetuses.

Warren argues that the phrase ‘human beings’ in premise 1 is intended to mean ‘moral persons’, while in premise 2 ‘human beings’ refers to ‘genetically human entities.’ If you were to replace the phrase 'human beings' in each premise with their definitions, the argument will no longer "flow", and it would be clearly invalid. (Try it!) Warren then makes the point that pro-lifers need to give an account of what gives humans moral personhood that includes fetuses. If they cannot, their argument fails. She concludes by giving her own criteria for moral personhood, which is as follows:

- Sentience (defined in the utilitarian sense)

- Emotionality

- Reason

- The capacity to communicate

- Self-awareness

- Moral agency, i.e., the capacity to make moral decisions

Warren stresses that fetuses at early stages of gestation have none of the relevant criteria; hence they are not moral persons; hence they have no rights. In later stages of pregnancy, fetuses perhaps have 1 of the criterion (sentience), but it would be unreasonable to insist, she argues, that this gives the fetus the same moral status as a full-fledged human. And thus, through an account of moral personhood that stresses the greater weight of cognitive capacities, she defends the pro-choice position.

There are several problems with this line of thinking about moral personhood. The first is that this account of personhood seems to allow for infanticide, the practice in some societies of killing unwanted children soon after birth. This is because, by Warren's own criteria, there are not many morally relevant differences between a late-term fetus and a newborn infant; they still seem to have, at most, only one or two of Warren's criteria for personhood. Moreover, consider a human that is in a permanent vegetative state or has severe cognitive disabilities. These, on Warren's account, would also (it seems) not have moral rights (Harris and Holm 2010: 117).

Chinese anti-infanticide

tract (circa 1800).

There is, of course, the account of personhood advocated by the utilitarians—one which utilizes the boundary of sentience. In other words, you are a part of the moral community just in case you have the capacity to feel pleasure and pain. Although there is disagreement about when the capacity for fetal pain begins (Harris and Holm 2010: 126), with some (Rokyta 2008) theorizing that the 26th gestational week is the best candidate for the origin of fetal sentience, it is agreed that fetuses do acquire sentience at some point during pregnancy. As such, on the simplest conceivable utilitarian account, fetuses become a part of the moral community when they acquire sentience, and hence their moral rights must be weighed when considering abortion. Generally speaking, then, abortion would be impermissible once the fetus acquires sentience. However, as was mentioned in The Trolley, some utilitarians (e.g., Singer 1993) argue that abortion and even non-voluntary euthanasia (after birth) is permissible on incurably ill or severely disabled individuals whose life experiences would net more suffering than pleasure. As is always the case with consequentialist moral reasoning, things get complicated since it all depends on context.2

There are other accounts of moral personhood, although none seem to be very persuasive—at least to me. There is the religiously-motivated view that we are imparted with a divinely-sent immortal soul. This is a metaphysically dense assumption that has little to no proof and is hardly convincing for anyone who is not already a believer. Moreover, one would have to still make the case for when the soul enters the fetus (see Death in the Clouds (Pt. II)). There's also the notion that all humans, by virtue of being humans, have moral rights. But, as Harris and Holm (2010: 118-19) point out, the assumption that 'our kind' has moral priority is morally problematic, as it has been throughout history. There's also the potentiality argument: that a fetus has moral rights because it (generally) has the potential to become a complex, intelligent, self-conscious human. The problem with this view, though, is that there are countless "potential humans." For example, if you are a woman of child-bearing age and have a suitable sexual partner nearby, there is a "potential human" right there—if you catch my drift. But do you really feel morally obligated to bring about this potential human?

Lafollette (1980)

Who has rights over and duties towards children?

At the end of his essay, Lafollette (1980: 196) suggests that the aversion towards parenting licenses comes from a deeply ingrained belief that parents either own or have an absolute sovereignty over their children. This brings us to the debate over who has rights over children. There are, it should be said, some advocates of what seems to many an extremely radical position: that children are being wronged by being maintained in an artificial state of dependence upon adults. Let's call this position child liberationists. Child liberationists argue that we should extend to children all the rights that adults have (Archard 2010: 94-99). I don't take this view very seriously since the empirical facts of child development suggest that children simply don't have capacity to acquire the independence of adults if "given the chance." Even as adults, it's clear that becoming independent requires the acquisition of skills that take time to build and that even adults can't fully develop sometimes. Laura Purdy puts it well:

“Granting immature children equal rights in the absence of an appropriately supportive environment would be analogous to releasing mental patients from state hospitals without alternative provision for them” (Purdy as quoted in Archard 2010: 98).

There are, however, some more generally-accepted positions on who has rights over children. First, there is the view of Thomas Hobbes. Let's call this the absolute subjection view. According to Hobbes, parental power is total. Parents may "alienate them... may pawn them for hostages, kill them for rebellion, or sacrifice them for peace" (Hobbes as quoted in Archard 2010: 100).

To 21st century ears, this view is horrifying, or in the very least sounds anachronistic. John Locke, who was mentioned in the previous section, had a more tame view on parent's rights over children. Locke argued that the authority of parents over children is natural, although it is not an absolute control like Hobbes argued. The parents' task is to rear the children well, for that is the social function of marriage. During this time, parents can be said to be the proprietors of the children, but they can't pawn them or sacrifice them—contra Hobbes. Call this the parental proprietorship view.

Another perspective is that of Robert Nozick, whose "experience machine" we encountered in The Trolley. His view can be referred to as the extension view, since it claims that children are an extension of the parent. Children, says Nozick, "form part of a wider identity you have" (Nozick as quoted in Archard 2010: 101). In other words, due to the procreative relationship between parents and children, parents have the right to bring up the child with the beliefs, views, values, and ways of life of the parent. The children are "organs" of the parents (ibid.).

Robert Nozick

(1938-2002).

The extension view contrasts nicely with the "right to an open future" view. Thinkers like Nozick see it as important that children acquire certain values and inherit (or continue) a certain identity (Archard 2010: 100). Those who advocate children's "right to a future", however, value the autonomous (or chosen) life of children. Put another way, advocates of children's "right to a future" want the children to be equipped with the reasoning faculties to make decisions for themselves, without having some identity or value system forced on them. For the advocate of children's "right to a future", parents have rights over but also duties towards their children: parents must maximize the capacities of the future adult so that they can be maximally free, exercising their own free and autonomous choices.

The preceding is all complicated enough. So, might as well introduce a further complication: the role of the state. There appears to be a spectrum of views with regards to the role of the state and the rearing of children. On one side of the spectrum is the "family state" view. This is the view that, ideally, the state should take exclusive responsibility for the rearing of children. The most famous advocate of this view is Plato. Plato (in)famously defended the notion that male-female pair-bonds should be abolished and that the Guardians (those that had been groomed to rule the state since they were children) would select which male-female pairs would mate and then hand their children to professional childcare specialists. The parents would never know their biological offspring. On the other side of the spectrum is the "state of families" view, which (once again) John Locke advocated. This is the view that parents not only have rights over their children (the parental proprietorship view) but that they have a right to privacy to rear their children without interference from and observation by the state.

Food for thought...

How much do we owe?

State intervention

Given the entry of the "right to an open future" view, we must now consider just how far state interventions should go if this view is true. But in a liberal society like ours—liberal in the classical sense that stresses civil liberties, the rule of law, and economic freedom—there appears to be a trilemma, i.e., an uneasy situation in which there are three competing options. James Fishkin identifies this problem for us (see Archard 2010: 105-06). Liberal societies have three principles that they tend to promote. The first is the principle of merit. This is simply the view that positions and wealth within society should be allocated only on the basis of qualifications and productivity. The principle of equal life chances states that children with the same potential should have the same life prospects for social advantage. In other words, if two children have equal potential, the chances of one of them shouldn't be hampered just because she grew up in, say, a predominantly Mexican neighborhood with poorly-funded schools. Lastly, the principle of family autonomy states that the government (i.e., the state) should not interfere with family life other than to provide the minimum conditions for the child's eventual participation in adult life, such as through compulsory public schooling.

Student living out of car.

These three principles seem plausible enough. The difficult choices comes when these principles begin to negatively counteract each other. In particular, it appears that the principle of equal life chances and the principle of family autonomy might be incompatible in certain respects. This is because it is fairly obvious that differences in socioeconomic status (SES) affect children's prospects for academic and social success. Food and housing insecurity and lack of reliable academic guidance are just two factors that could negatively impact the academic prospects of children in low SES households. So what should be done?

The tendency appears to be to want to avoid Plato's totalitarian state, where the children are reared by the state—although reared very well, one might add. Even though, in theory, the children are raised well, maximizing each of their potentials, there are many unsavory aspects to Plato's social order: complete submission to authoritarian rulers, the abolition of marriage, etc. However, the condition of having no state intervention is equally undesirable. Not only will this mean that low SES families are given no assistance, essentially ensuring that society will never capitalize on the child's potential talent, but some families might instill in their children ideas that are contrary to academic and social success, not to mention the public good (see the Food for thought). Ideally, there should be some middle position, but it is difficult to know where to draw the line. Should all families with parents be given the basic necessities and resources to rear children? Should something like a universal basic income be instituted? Should all children spend part of their lives in something akin to boarding schools, where the state can provide the necessary housing, environment, and sustenance for good education? Not to sound like Plato but—can we really trust parents with something as important as a child's education? It seems fitting to end this subsection with the words of J.S. Mill:

“It is in the case of children that misapplied notions of liberty are a real obstacle to the fulfillment by the state of its duties. One would almost think that a man's children were supposed to be literally, and not metaphorically, a part of himself, so jealous is opinion of the smallest interference of law with his absolute and exclusive control over them” (Mill as quoted in Archard 2010: 107).

Ideological freedom?

Note that the preceding discussion made one very big assumption without any real defense: that the knowledge that the state imparts is actually valuable (or preferable to what parents can impart). This is not the place to enter into a full analysis of the educational system (although I do dive into this in my teaching trilogy in my PHIL 105 course). Let's concentrate instead on one possible effect that the curriculum has on children: influencing their values.

One K-12 teacher (B. Hernández) that I reached out to for information about ideology in the classroom put it bluntly, "There’s no apolitical classroom, there’s no neutral classroom, it’s impossible." Hernández made the case that ideology influences education at every conceivable stage, beginning with what's chosen for inclusion in the curriculum as well as what's excluded. She stressed the importance of teaching in a socially inclusive way:

“If we choose to include diverse stories and perspectives in our curriculum and we have conversations about bias and racism, obviously we’re impacting our students ideologically. If we don’t have those conversations, we’re also impacting them ideologically—just in the opposite way... [So] we need to be conscious about the messages students are getting, based on what we do and teach in our classrooms” (Hernández, personal communication).

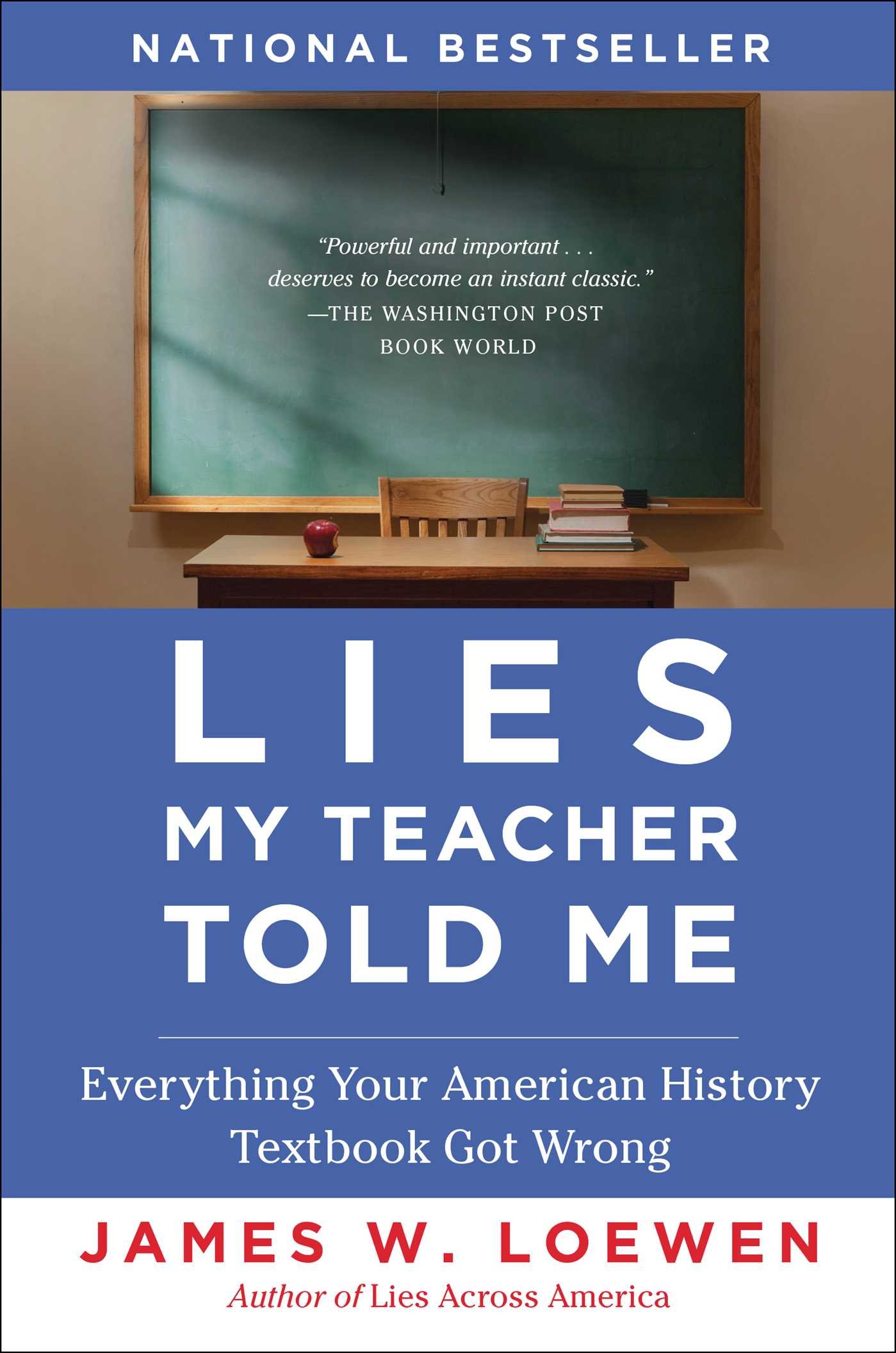

Inclusivity is one value that students can have imparted on them. Another is blind patriotism. In his Lies my teacher told me, James Loewen argues that the American k-12 history curriculum has been sanitized and distorted so as to primarily emphasize positive aspects of the nation's history, while deliberately ignoring or "Disneyfying" aspects of American history that are either morally problematic, like slavery and relations with Native Americans, or do not fall in line with the political status quo. For example, most students know about Helen Keller overcoming her disabilities, but they don't know that she was a radical socialist. Most students also know that Martin Luther King Jr was the country's most famous agitator for civil rights, but they don't tend to know how vociferous King was against American aggression abroad, calling the United States government "the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today."

Perhaps even more important than teaching (or not teaching) inclusivity and patriotism, we should consider whether the educational system, as it is currently constituted, actually imparts on students critical thinking skills. To be honest, the available evidence does not make it apparent that the educational system is at all effective (Caplan 2018). I don't need to tell you that this is bad. Many teachers are worried. My colleague and friend Josh Casper shares these sentiments:

“Education that focuses on rote memorization and preparation for standardized tests fails, not only our students, but our society by creating generations of memorizers and test-takers and not generations of critical thinkers. History never fully repeats itself, but it rhymes with itself; therefore, an education system that fails to imbue students with the requisite tools of critical thinking will create a society founded on popular docility, mass apathy, and oppression” (Casper, personal communication).

Should the state take initiative in influencing children's values so that they are more inclusive? Should we make students more patriotic? Perhaps a consequentialist argument can be made for one of these positions, arguing that more inclusive or patriotic students would be (overall) better for the public good. Having said that, this might fly in the face of the principle of family autonomy. (What if the children's families shun inclusivity and/or patriotism?) Should we make students better critical thinkers? Would this be better for society? That's a legitimate question that rational people might actually disagree about. This is a trilemma indeed.

Segregation(?)

As one final example of how the state might intervene to maximize children's educational potential, perhaps the right way to move forward in k-12 education is to eliminate co-ed education, opting for only same-sex classrooms:

“According to difference feminists [see The Gift], co-ed classrooms are one of the primary places where men's gender dominance over women is created and maintained. For example, a significant percentage of teachers (female as well as male) tend to praise boys more than girls for equal-quality work; encourage boys to try harder; and give boys more interactive attention (Hall and Sandler 1982: 294). Thus, girls and women need same-sex classrooms, not because female students are less academically capable than male students, but because such classrooms constitute an environment friendly to women's concerns, issues, interests, needs, and values” (Tong 2010: 226).

Coming of age...

The trajectory of this unit is pretty straightforward. Now that the normative questions surrounding childhood have been explored, we will move forward in the life cycle to discuss the various ethical choices one makes as they get older. Once compulsory schooling is over (and sometimes before it's actually over), American students face the choice of whether or not to enlist in the armed forces. We'll take that question up—and much more— in Thucydides' Trap. Another important set of decisions young adults have to make surround love and marriage; these will be discussed in The Gift. Concurrently with deciding who to marry and whether or not to enlist, young people are making decisions at the ballot box. In Seeing Justice Done, we'll consider the moral dimensions of policing and punishment—topics you may have to vote on. After that, we'll think about our relationship to animals (The Jungle), money (The Game), and drugs (Prying Open the Third Eye). We close with a reflection on death in The Troublesome Transition.

The topic of abortion is broached primarily in order to discuss theories about moral personhood. The views explored include theories that ascribe personhood to those who have certain intellectual capacities (Kant and Locke) and those that are sentient (utilitarianism), as well as less popular views (religiously-motivated views and the potentiality view).

Lafollete (1980) argues that, due to the fact that parenting is an activity potentially very harmful to children, society ought to require parenting licenses of all those who want to have and raise children.

There are various views with regards to who has rights over children, as well as whether we have duties and obligations to children beyond ensuring survival. We covered the child liberationist view, the absolute subjection view, the parental proprietorship view, Nozick's extension view, and the "right to an open future" view.

We closed with different views on how the state can intervene to ensure children have a maximally good future. Topics covered included state interventions to correct differences in socioeconomic status, values being taught in the classroom, and the abolition of co-ed classrooms.

FYI

Suggested Reading: Mary Anne Warren, On the Moral and Legal Status of Abortion

Supplemental Material—

-

Reading: Don Marquis, Why Abortion is Immoral

-

Reading: Judith Jarvis Thomson, A Defense of Abortion

- Reading: Hugh Lafollette, Licensing Parents

Related Material—

- Podcast: Freakonomics, Abortion and Crime, Revisited

-

Audio: Fresh Air, Interview with Richard Rothstein on his book The Color of Law.

-

Reading: Noa Yachot, History Shows Activists Should Fear the Surveillance State

Video: James Loewen,Interview on Lies My Teacher Told Me

Advanced Material—

-

Reading: Richard Rokyta, Fetal Pain

Footnotes

1. Note that 1973 is the same year that Roe v Wade was decided, after two years of arguing and re-arguing.

2. There's also some interesting empirical data that legalizing abortion may have had a positive impact on crime rates.