When in Rome...

How are you going to teach virtue if you teach the relativity of all ethical ideas? Virtue, if it implies anything at all, implies an ethical absolute. A person whose idea of what is proper varies from day to day can be admired for his broadmindedness, but not for his virtue.

~Robert M. Pirsig

Logical Analysis

Refresher

Today we reassess cultural relativism. Relativism was alluring to many intellectuals who were disenchanted with Western values after witnessing the pointless brutality of World War I (Brown 2008: 364-5). It appears that once you've been wholly alienated from your own culture's values, you are more capable of seeing other cultures in a new light, with fewer reservations and with a renewed commitment to assess these alien cultures by their own internal logic. Students today are also attracted to the view because it makes the somewhat obvious point that cultural evolution plays a dominant role in why we see so much variance in the world's moral codes. Moreover, prior to the introduction of radical moral skepticism into the fray, anyone that denied that moral properties are mind-independent (i.e., moral non-objectivism) could only choose between relativism, Hobbes' social contract theory, and ethical egoism. And, to be honest, cultural relativism does seem like the most palatable of these. However, some theorists argue that, not only is relativism false, it's dangerous as well (see the next section).

But before we begin our reassessment, let's remind ourselves of some important features of classical cultural relativism. Relativism, at least in its classical form (which is the one we are covering), accepts the notion of relative truth. That is to say that cultural relativists believe that some things can be true for some people. This is an epistemic position, a philosophical position about the nature of truth. These kinds of philosophical positions cannot be demonstrated through empirical experimentation; rather, they have to be argued for. However, cultural relativism does make an empirical claim—the second thing we have to remind ourselves of. The relativist claims that there are major differences in the moralities that people accept but that these differences do not seem to rest on actual differences in situation or disagreements about the facts. In other words, in different cultures, people generally agree on the facts and on the similarity of their situations but yet they still have different values.

Important Concepts

Before reassessing classical cultural relativism, let's also perform a logical analysis of the view itself as well as the argument put forward for the view. To this end, we will need to learn some new logical concepts. We'll learn those in the Important Concepts below.

The quest for soundness

When first learning the concepts of validity and soundness, students often fail to recognize that validity is a concept that is independent of truth. Validity merely means that if the premises are true, the conclusion must be true. So once you've decided that an argument is valid, a necessary first step in the assessment of arguments, then you proceed to assess each individual premise for truth. If all the premises are true, then we can further brand the argument as sound. If an argument has achieved this status, then a rational person would accept the conclusion.1

Let's take a look at some examples. Here's an argument:

- Every painting ever made is in The Library of Babel.

- “La Persistencia de la Memoria” is a painting by Salvador Dalí.

- Therefore, “La Persistencia de la Memoria” is in The Library of Babel.

Jorge Luis Borges

(1899-1986).

At first glance, some people immediately sense something wrong about this argument, but it is important to specify what is amiss. Let's first assess for validity. If the premises are true, does the conclusion have to be true? Think about it. The answer is yes. If every painting ever is in this library and "La Persistencia de la Memoria" is a painting, then this painting should be housed in this library. So the argument is valid.

But validity is cheap. Anyone who can arrange sentences in the right way can engineer a valid argument. Soundness is what counts. Now that we've assessed the argument as valid, let's assess it for soundness. Are the premises actually true? The answer is: no. The second premise is true (see image below). However, there is no such thing as the Library of Babel; it is a fiction invented by a poet named Borges. So, the argument is not sound. You are not rationally required to believe it.

Here's one more:

- All lawyers are liars.

- Jim is a lawyer.

- Therefore Jim is a liar.

You try it!

Cultural relativism seen anew

With all the moving parts in place, we can now rebuild our argument for cultural relativism. It is as follows:

- There are major differences in the moralities that cultures accept.

- If different cultures accept different moralities, then each culture’s morality is true for them. (This is the missing premise.)

- Therefore, each culture’s morality is true for them.

The argument appears to be valid. In fact, it is in a pattern known as modus ponens, which is a pattern of reasoning that is always valid. With validity established, we can move on to assess the argument for soundness, i.e., to check whether the premises are actually true. Premise 1 appears to be true. In fact, it is obviously true: there are widely different sets of accepted customs and practices. The question, though, is whether or not premise 2 is true. Accepting this premise as true is to implicitly accept the notion of relative truth. Thus, we move on to that topic next.

Alethic relativism

We've seen that the argument for classical cultural relativism requires the truth of the notion of relative truth if it is to be sound. This "notion of relative truth" actually has a name, which I've avoided stating until now. It is called alethic relativism: the claim that what is true for one individual or social group may not be true for another. It appears that alethic relativism is essential to all forms of relativism (including our classical moral relativism) since all (or most) other forms of relativism are in principle, reducible to alethic relativism (see §3.4 of the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy's entry on Relativism.

So the view on truth needed so that the argument for cultural relativism is sound has a name, but it also has many critics. The most common charge against the alethic relativist, it seems, is the accusation of self-refutation. In other words, those who disagree with alethic relativism accuse those that do of the most loathsome trait that can be found in a philosophical theory: the claim that the view refutes itself. Consider this. By its own logic, the theory of alethic relativism would have to be relative. So if you believe that truth is relative, as a relativist, you can only really say that that's the truth for you. In other words, if you are an alethic relativist and I am not, there seems to be no way that you can convince me that your view is true; by your own logic, you can only state that my view is true for me and your view is true for you. A version of this argument goes back to Plato (see Plato's Theaetetus: 171a–c):

- Most people believe that Protagoras’s doctrine is false.

- Protagoras, on the other hand, believes his doctrine to be true.

- By his own doctrine, Protagoras must believe that his opponents’ view is true.

- Therefore, Protagoras must believe that his own doctrine is false.

Donald Davidson (1917-2003).

Of course, this relativizing of truth appears to be either absolutely absurd (collapsing the distinction between truth and falsity) or at least terribly misleading. According to Donald Davidson, if alethic relativism were true, then this would make translation between different languages impossible. According to Davidson, assuming that other people (in general) speak truly is a pre-requisite of all interpretation (ibid.). So, if people from different cultures went around using their own personal notions of truth, then two people from different cultures would never be able to communicate. Obviously, communication between cultures does occur—even if there are occasional hiccups. Alethic relativism, then, appears to be self-defeating and entirely at odds with our commonsense notions of translation and the distinction between truth and falsity.

The debate over alethic relativism is ongoing, however. Thus, the best we can do in this course is allow the matter of the truth of alethic relativism to remain an open question. Nonetheless, we can at this point say this. The argument for classical cultural relativism explored in this course is not sound, since the premises are not all known to be true. This is not to say that it is unsound. We can only say we have to leave it at that.

Food for thought

Other conceptual considerations

Rachels (1986) argues that accepting cultural relativism has some counterintuitive implications, such as:

- We could no longer say that the customs of other societies are morally inferior to our own. But clearly bride kidnapping is wrong.

- We could decide whether actions are right or wrong just by consulting the standards of our society. But clearly if we were to have lived during segregation, consulting the standards of our society would've resulted in believing that segregation is morally permissible (and that's obviously false).

- The idea of moral progress is called into doubt. For example, if we are relativists, then we could not say that the end of the Saudi ban on women driving is moral progress (but it clearly is).

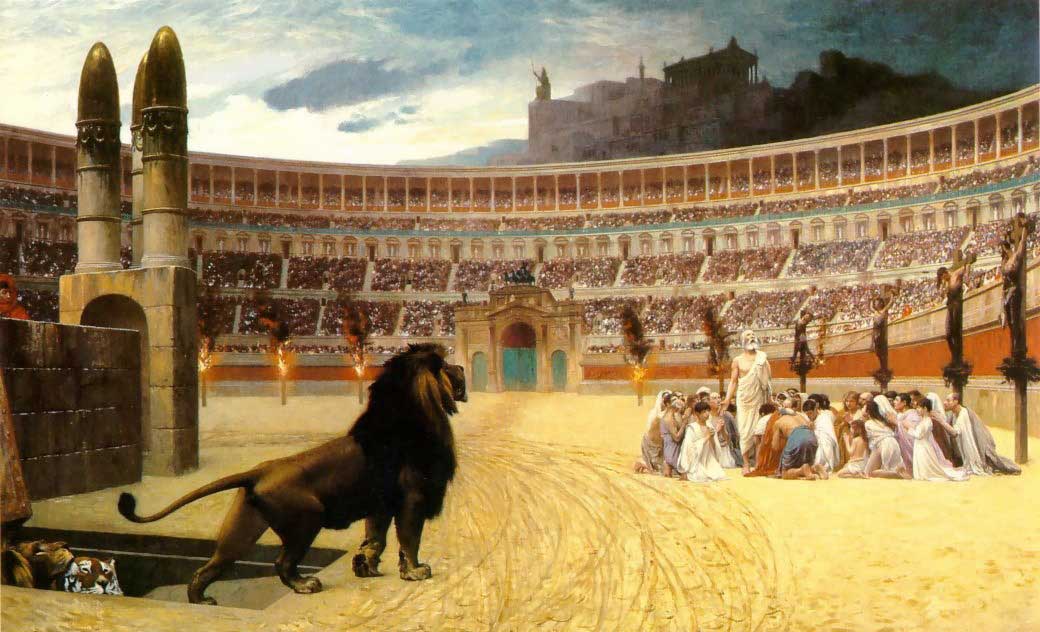

Damnatio ad bestias.

Let's take a specific example to make this more clear. If cultural relativism is true, then we cannot even morally judge some ancient Roman practices. Romans and their subject peoples would gather to watch various events that today we would find morally reprehensible. For example, public executions were held during lunch time at their many colosseums. These executions sometimes were by way of damnatio ad bestias (Latin for "condemnation to beasts"). In these grizzly executions, criminals, runaway slaves, and Christians were killed by animals such as tigers, lions, and bears. Floggings were regular, as was gladiatorial combat, which sometimes (but not always) would result in death. There was animal-baiting and animal battles, such as when Pompey staged a fight between heavily armed gladiators and 18 elephants. Personally, though, the spectacle I find the most gruesome was the fatal charades. These are plays in which the plot included the death of a character. And so, these stories were acted out by those condemned to die and their the deaths were real (see Fagan 2011 and Kyle 2001).

The practices of the Romans are questionable even when we look past the Roman games. For example, they appear to have come to sound moral conclusions but for the wrong reasons. Fagan describes an instance of this:

“One of the chief arguments against maltreatment of slaves in the ancient sources is not the immorality of handling a fellow human being harshly but the deleterious effect such behavior had on the psyche of the owner and the loss of dignity inherent in losing one’s temper” (Fagan 2011: 24-5).

Clearly, though, the reason why we shouldn't treat fellow human beings harshly is because they have dignity and equal moral worth. It does not have to do with how undignified it is to lose one's cool. This would be like saying that someone who punches their child in the face in public is doing something wrong because losing one's cool like that is best done in the home. Clearly, the wrongness comes from what is being done to the child. But the Romans seemed to not have recognized this, at least when it came to slaves. That seems morally condemnable.

Summary of conceptual issues regarding cultural relativism

In short, not only does classical cultural relativism need alethic relativism for a proper defense of the view, which entails (among other things) collapsing the distinction between truth and falsity and doing away with the possibility of translation, but also it does away with intuitive notions like that of moral progress. So, it seems that based on conceptual issues alone, classical cultural relativism is untenable, i.e., not capable of being defended. But we still have to assess its empirical claims. We move to that task next.

When in Rome: Moral Relativism, Reconsidered

Too absolutist(?)

La Piedra del Sol.

It has been brought up during class by students who are sympathetic to cultural relativism that the denial of cultural relativism might be morally disastrous in its own way. For example, if cultural relativism isn't widely believed by people, then people will think that it is ok for some people to invade different cultures to ameliorate their questionable moral practices. Under this way of thinking, perhaps the conquest of the Mexica people by the Spaniards is morally justified in that at least the Spaniards ended the practice of human sacrifice. This, goes the objection, is not ok, though, since cultures should be preserved but are instead being erased by this moral absolutism.2

It is true that some counterintuitive cultural practices do stabilize in a given region and become a cultural representation. Adam Smith himself reflected on this. In his Theory of Moral Sentiments (part 5, chapter 2), Smith first argues that the moral sentiments are not as flexible as the sentiments associated with beauty. In other words, it seems like norms regarding beauty vary much more widely than do norms regarding what is virtuous behavior. For example, no set of customs will make the behavior of Nero agreeable—behaviors which included the murder of his mother and engaging in lots of sexual debauchery. Smith also mentions that some practices, such as infanticide, have stabilized in certain societies because they were first practical. Only after this stage of practicality were they preserved by custom and habit. He makes the case that “barbarous” peoples are sometimes in a perpetual state of want, never being able to secure enough sustenance for themselves. It is understandable, Smith argues, that in these communities, infants should be exposed to the elements, since to not do so would only produce a dead parent and child, rather than just a dead child. Smith ultimately disapproves of this practice, of course, but he is making a case for how this practice can become part of a culture.3

The 'No female genital

mutilation' symbol.

In any case, the point of this digression is to suggest that the rejection of cultural relativism does not necessarily require the acceptance of moral absolutism. In theory, they could both be wrong. One could, of course, opt for something like moral sentimentalism or radical moral skepticism. Despite the label "radical", radical moral skepticism is actually far more amenable to a sort of "middle position". A skeptic might say the following. It is a good principle to respect the cultural practices of others, if there is no fundamental disagreement on the facts. But too many cultures believe blatantly false propositions, for example that having sex with a virgin can cure HIV or that women are not competent to represent their own interests. These practices appear to be both factually and morally wrong. But the invasion of other countries to ameliorate unjustified practices might also be morally wrong. In other words, we can say no to both. The main point here is that several morally abhorrent practices are protected by the invisible shield of cultural relativism. But the notion is ludicrous. It would be better to explain the phenomenon through a careful analysis, like that of Smith, and try to figure out how to update the beliefs of people so that these unfair, unreasonable practices can be stopped. Steven Pinker expresses these sentiments well:

“If only one person in the world held down a terrified, struggling screaming little girl, cut off her genitals with a septic blade, and sowed her back up, leaving only a tiny hole for urine and menstrual flow, the only question would be how severely that person should be punished and whether the death penalty would be a sufficiently severe sanction. But when millions of people do this, instead of the enormity of being magnified millions fold, suddenly it becomes culture and thereby magically becomes less rather than more horrible and is even defended by some Western moral thinkers including feminists” (Pinker 2003: 273).

In this lesson, we focused on two aspects of classical cultural relativism: the conceptual matter of the truth of alethic relativism, the claim that what is true for one individual or social group may not be true for another, and the empirical claim that disagreements in value do not stem from disagreements about the facts; we also reformulated our argument for classical cultural relativism—filling in the missing premise—and briefly looked at other conceptual issues with relativism.

With regards to alethic relativism, it is certainly not obvious that it is true. In fact, it is not clear how relativists can overcome the charge of self-refutation.

Moreover, it appears that moral relativism is incompatible with the notion of moral progress. However, it appears that moral progress does exist. So, we must conclude that classical cultural relativism is conceptually untenable.

Lastly, the one empirical claim made by classical cultural relativists appears to be false. In fact, cultures with widely-divergent practices routinely disagree on the facts.

FYI

Suggested Reading: James Rachels, The Challenge of Cultural Relativism

Supplemental Material—

-

Video: BBC Ideas (A-Z of ISMs Episode 18), Relativism: Is it wrong to judge other cultures?

Reading: Maria Baghramian and J. Adam Carter, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Relativism

Advanced Material—

-

Reading: Michael F. Brown, Cultural Relativism 2.0

- Note: Brown abandons classical cultural relativism, and instead promotes his own brand.

Footnotes

1. Another common mistake that students make is that they think arguments can only have two premises. That's usually just a simplification that we perform in introductory courses. Arguments can have as many premises as the arguer needs.

2. James Maffie, in his chapter of Latin American and Latinx Philosophy: A Collaborative Introduction, argues that the Mexica did not practice human sacrifice, properly speaking. This is because sacrifice entails the process of making sacred, which can be seen from the etymology of the word (sacer meaning "holy" or "sacred" and facere meaning "to make"). However, for the Mexica, everything was sacred. Rather, the Mexica engaged in reciprocal gift-giving with the gods. So, there is plenty of evidence that the "obligation repayments" of the Mexica to the gods did include human bloood and hearts; however, according to Mexica logic, these wouldn't really be sacrifices, perse (see Sanchez 2019: 13-35).

3. Recall that John Miller and Scott Page note that Smith’s work is an early example of complexity studies. Smith also seems to be discussing moral norms as the products of social dynamics.